The thyroid gland, which is situated below the larynx, secretes hormones that regulate many biological and metabolic processes, including growth, development, and energy expenditure. Both the over- and underproduction of thyroid hormones lead to a variety of clinical symptoms, many of which overlap with other conditions and are therefore easily misdiagnosed. It is estimated that 1 in 7 Australians will be affected by some form of thyroid disorder during their lifetime.[1] Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland) is the most common thyroid disorder and may be related to insufficient dietary iodine intake.

THYROID HORMONES

Follicular cells in the thyroid gland produce the two primary hormones, tetraiodothyronine (commonly referred to as thyroxine or simply T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). The numbers

3 and 4 refer to the number of iodine atoms present within the hormone molecule.

T3 is the most active form of thyroid hormone. T4, on the other hand, is longer lasting and can be converted to T3 by enzymes that remove one iodine atom (monodeiodination). This conversion occurs in the peripheral tissues, which can therefore serve as a reservoir for T3.

Thyroid hormones are required for normal brain and somatic tissue development in the foetus and neonate, and, in people of all ages, regulate protein, carbohydrate and fat metabolism.[2] The greater the amount of T3 and T4 circulating in our blood, the faster our metabolism. Lower amounts of these hormones result in a reduced or sluggish metabolism.

REGULATORY MECHANISMS

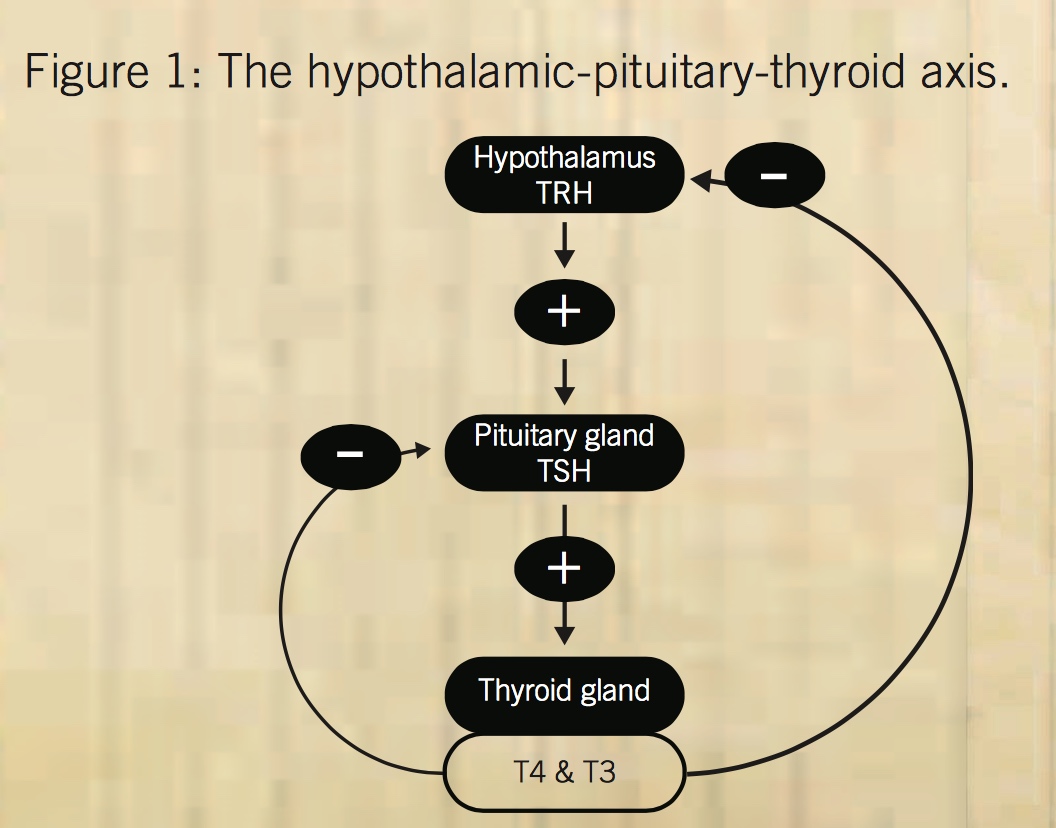

The activity of the thyroid gland is controlled by a complex process involving the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. In response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) secretion by the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland secretes thyroid- stimulating hormone (TSH), which stimulates iodine trapping, thyroid hormone synthesis, and release of T3 and T4. The presence of adequate circulating thyroid hormones reduces TRH and TSH production (see Figure 1).

OVERACTIVE THYROID (HYPERTHYROIDISM)

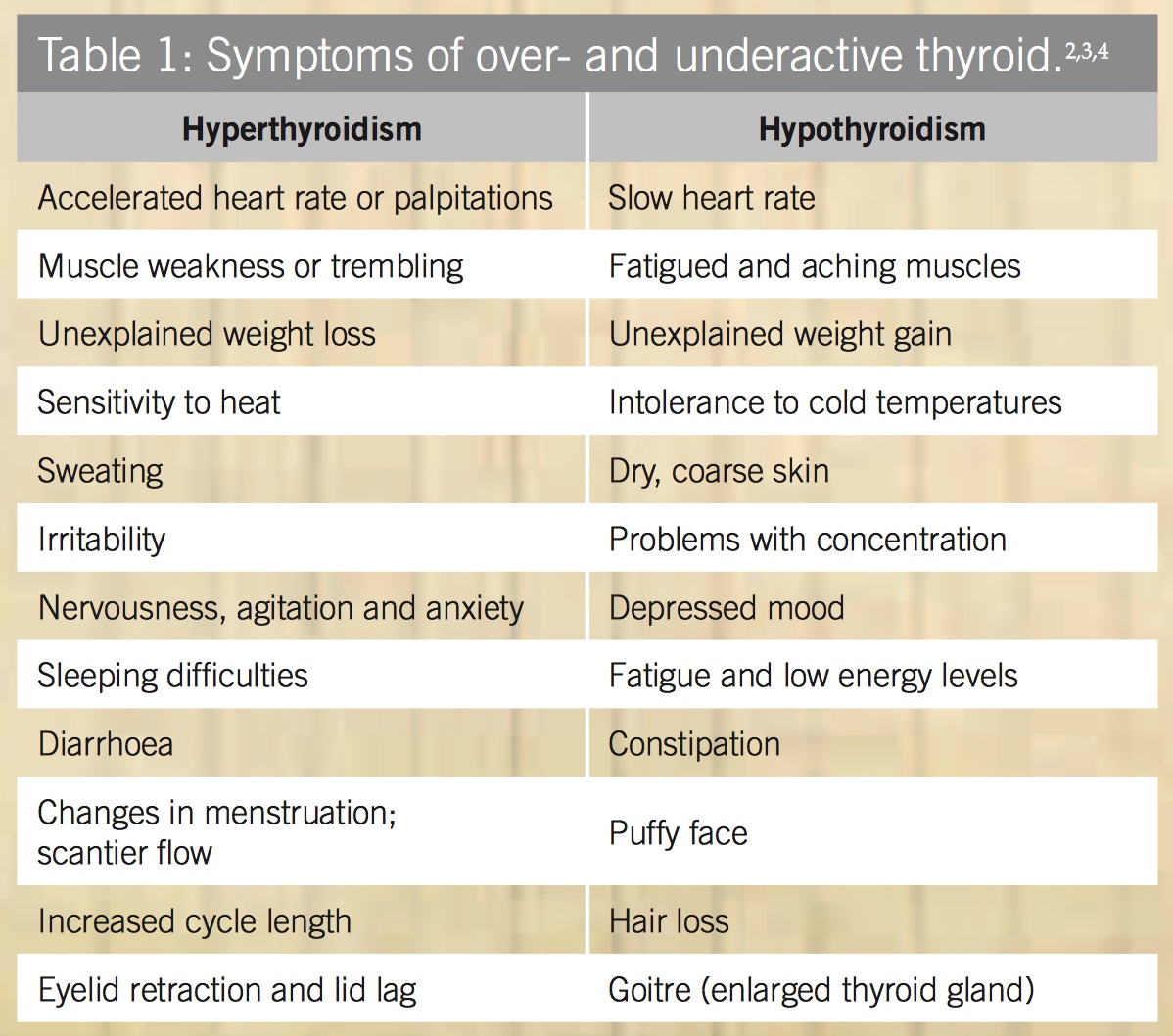

Hyperthyroidism is characterised by elevated serum levels of thyroid hormones and hypermetabolism. A common cause of hyperthyroidism is Grave’s disease, an autoimmune disease in which antibodies behave like TSH and stimulate the thyroid uncontrollably. Other causes can include local inflammation and nodules. Symptoms of an overactive thyroid are summarised in Table 1.

UNDERACTIVE THYROID (HYPOTHYROIDISM)

An underactive thyroid releases too little thyroid hormone, causing the metabolism to slow down. Hypothyroidism can be either primary (the thyroid gland itself is diseased) or secondary (caused by problems within the pituitary gland or hypothalamus).

Hypothyroidism is the most common thyroid disorder affecting about 6-10% of women.[4] However, the prevalence increases with age and up to 25% of women aged 65 years or older may be affected.[4] Men are also affected, but less frequently.

In addition to iodine deficiency, another common cause of hypothyroidism is Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune disease in which antibodies attack the thyroid gland. Other possible causes include treatment for hyperthyroidism and particular medications (e.g. lithium).[4] Symptoms of an underactive thyroid are summarised in Table 1.

DIAGNOSIS

In addition to the symptom picture of each condition, both hyper- and hypothyroidism can be diagnosed with a simple blood test that measures hormone levels. A person with hyperthyroidism will generally have normal (subclinical hyperthyroidism) to high levels of free T4 and/or T3, but low levels of TSH.[2,3] The presence of thyroid stimulating antibodies confirms the presence of Grave’s disease.

Primary hypothyroidism typically manifests as elevated TSH and low T4 levels. Secondary hypothyroidism occurs when the hypothalamus produces insufficient TRH or the pituitary produces insufficient TSH. Secondary hypothyroidism is therefore characterised by low levels of both TSH and T4.[2]

UNDERACTIVE THYROID AND WEIGHT GAIN

In overt (clinical) hypothyroidism, decreased thyroid hormone activity leads to weight gain through reduced basal metabolic rate, exacerbated by reduced motivation to engage in physical activity.[5] Several population- based studies have shown a significant association between TSH level and BMI (body mass index). Researchers have found that even a modest increase in serum TSH concentrations may be associated with weight gain.[6]

IODINE FOR THYROID HORMONE PRODUCTION

The primary role of iodine in the body is the synthesis of thyroid hormones. The thyroid gland needs about 150mcg of iodine daily for sufficient hormone production.[4] Failure to satisfy this requirement leads to hypothyroidism. In response to reduced blood levels of thyroid hormones, the pituitary gland increases output of TSH. Persistently elevated TSH levels may lead to hypertrophy of the thyroid gland, also known as goitre. Goitres are estimated to affect more than 200 million people worldwide. In all but 4% of these cases, the cause is iodine deficiency.[7]

IODINE STATUS IN AUSTRALIA

In 2008, the 22nd Australian Total Diet Study reported that between 7% and 84% of various population groups (based on age and gender) had inadequate dietary intakes of iodine,[8] the figure increasing markedly with increasing age.

Findings in women of childbearing age were of particular concern as about 66% of women aged 19-29 years and 73% of women aged 30-49 years were found to have insufficient intakes. Thus, a substantial proportion of Australian women enter pregnancy with inadequate iodine status. More than 50% of men aged 50 years and older fail to consume the estimated average requirement of 100mcg daily.

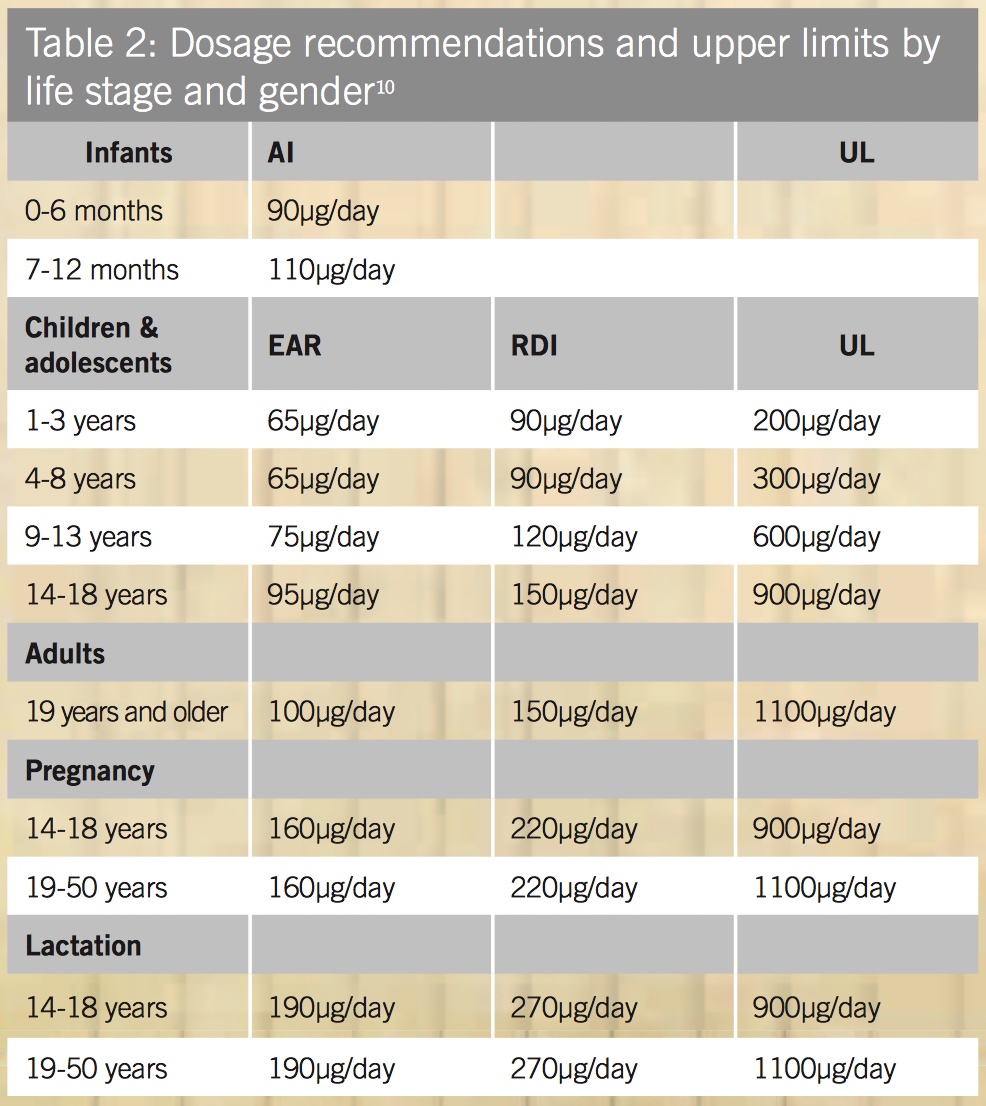

In an attempt to address the widespread nutrient inadequacy, all types of non-organic bread produced in Australia were then required to be fortified with iodised salt. However, one serve of bread (2 slices) typically provides 28mcg of iodine,[9] falling far below the recommended daily intake as presented in Table 2.

A 2012 media release by the Australian Thyroid Foundation (ATF) suggested that between 20,000 to 30,000 women each year are at risk of developing a thyroid problem during pregnancy, putting their babies at risk of brain damage.[11] The ATF supports the National Health and Medical Research Council’s recommendation for all pregnant women to take a daily pregnancy supplement containing 150mcg of iodine.[12]

References

- Media alert: Thyroid awareness week, 1-7 June 2011. The Australian Thyroid Foundation Ltd. [Link]

- Hershman JM. Thyroid disorders. The Merck manual [online]. Merck & Co., Inc. [Link]

- Thyroid disorders – hyperthyroidism. Better Health Channel. State Government of Victoria, Sep 2012. [Link]

- Thyroid disorders – hypothyroidism. Better Health Channel. State Government of Victoria, Sep 2012. [Link]

- Kitahara CM, Platz EA, Ladenson PW, et al. Body fatness and markers of thyroid function among U.S. men and women. PLoS One 2012;7(4):e34979. [Full Text]

- Fox CS, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, et al. Relations of thyroid function to body weight: cross-sectional and longitudinal observations in a community-based sample. Arch Intern Med 2008;168(6):587-92. [Full Text]

- Murray MT, Bongiorno PB. Hypothyroidism. In: Pizzorno JE Jr, Murray MT (Eds), Textbook of natural medicine, 3rd ed (pp.1791-9). St Louis: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2006.

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). The 22nd Australian Total Diet Study. Canberra: FSANZ, 2008. [Link]

- Iodine in food (September 2012). Food Standards Australia New Zealand, Sep 2012. [Link]

- Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council, Ministry of Health. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Commonwealth of Australia, 2006. [Link]

- Media release – Women planning or expecting a baby urged to get thyroid tested this Mother’s Day. The Thyroid Foundation Ltd, 13 May 2012. [Link]

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.