Most people have an awareness that thyroid disorders exist, or maybe even have an understanding that goitre (enlargement in the throat/neck area) is characteristic of a thyroid disorder. But ask the average person what their thyroid actually does and you’re likely to be met with a blank stare.

So, what does the thyroid do?

Put simply, the thyroid is responsible for regulating the rate and rhythm of all cells in the body. The thyroid is like the spark plug that gives energy to the body. It controls a person’s metabolic rate via the hormones it produces and influences body temperature.

With a hyperthyroid (overactive) the body runs essentially “too hot” or “too fast”, whereas in contrast, a hypothyroid (underactive) causes the body to run “too cold” or “too slow”.

Body temperature, ideally taken first thing in the morning on waking, can be a barometer of thyroid health. It is believed that for each degree of temperature loss, the body’s metabolic rate decreases by approximately 6%.[1] You can imagine then, the impact of a two to four degree temperature drop - it would mean a 12-24% decrease in metabolic function, which is why those with hypothyroid can feel fatigued, unmotivated and depressed, leading to challenges with weight.

How common is hypothyroidism?

In Australia, the incidence of thyroid disorders is likely under-reported. Statistics claim it affects around 2% of the population.[2] However, evidence suggests, if more screening took place this number would climb. For instance in one WA study of 2115 adults, it was found that there was a 12.4% incidence of thyroid antibodies amongst subjects without a previous history of thyroid disease.[3] Thyroid disease is typically more common in women than men.

What causes hypothyroid?

Iodine deficiency is considered the most common cause of hypothyroidism worldwide, and autoimmune chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis is the most common aetiology in iodine replete countries such as Australia.[4]

Australia is considered a “replete” nation of iodine, because we have a high consumption of seafood and our food supply is heavily fortified with iodine. However, despite these measures, iodine deficiency is still common.

One potential cause of compromised iodine status, is the effect of antagonistic elements we are exposed to in our environment, lifestyle or food supply. Examples such as heavy metals (e.g. lead, mercury and cadmium), and in particular chlorine and fluoride as these mineral elements compete with iodine in the body, rendering it unavailable for the production of thyroid hormones.

Where do we come into contact with these elements, you might ask? Look no further than the water supply, fresh produce (washed), cleaning products, toothpaste, exhaust fumes and cigarette smoke, to name a few.

Another barrier to the body having optimal access to iodine is the consumption of goitrogens. These can be derived from certain drugs a well as food. Certain foods, if over-consumed or improperly prepared, can impair iodine uptake and affect metabolism. These foods include those which are in fact very healthy and nutritious such as: kale, flax seed, spinach, soybeans and the brassica family of vegetables (cabbage, broccoli and cauliflower). Care needs to be taken with an underactive thyroid to prepare these foods properly, or keep them to a minimum, in order to optimise the uptake of iodine.

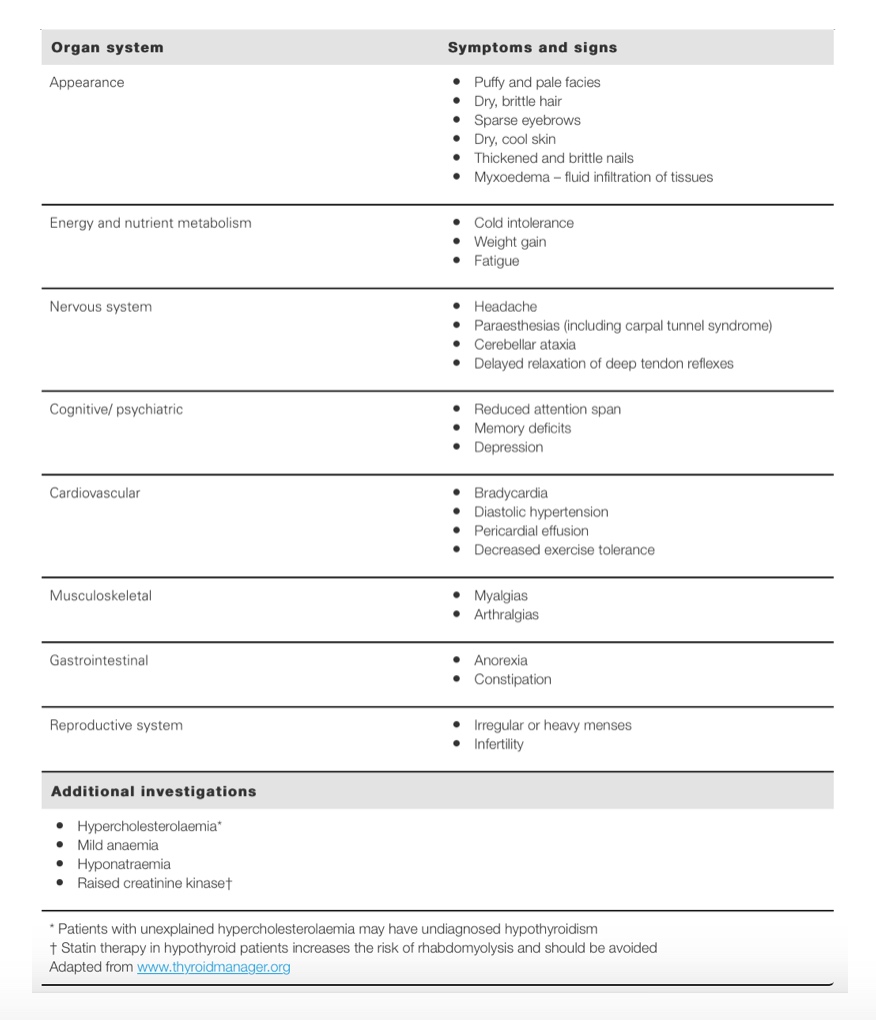

What are the signs and symptoms of a thyroid disorder?

The most common symptoms to be on the look out for are brittle, dull or lack lustre hair, skin and nails. People with hypothyroid also tend to feel the cold more easily and they’re often quite fatigued, even by normal activities. Other characteristic features may also include a foggy mind or memory, anxiety and heart palpitations.

Another very simple way to self-investigate the thyroid is to take the basal body temperature. This is performed with a mercury thermometer popped into the armpit for five minutes before getting out of bed to start the day.

It is important to take it before rising, because movement influences body temperature and you want to get an indication of what the thyroid is doing at rest after eight hours sleep. Ideally a consecutive week of temperatures is needed to get a clear picture of the average basal temp (*menstruating women are best to do this from around day 2 of their period, as mid-cycle ovulation gives body temperature a temporary boost).

If the average temperature is less than 36.4ºC and this is combined with other thyroid symptoms (refer to table) then it’s worthwhile having a healthcare practitioner run some tests.

Symptoms, signs and additional investigation findings in hypothyroidism[4]

What are the tests for thyroid disorders?

The standard medical test is to check thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). However this is only one marker of thyroid activity and does not give you the whole picture of what is happening. Ideally, we need to be checking for TPO antibodies (thyroid antibodies) as well as the thyroid hormones themselves: T4, free T3 and reverse T3.

It is quite common for people to be told their thyroid function is normal as their TSH levels return in the healthy reference range, yet they experience virtually all of the clinical symptoms of hypothyroid. The true state of the thyroid health is often only revealed with these deeper investigations.

What about treatment?

Medically, the classic treatment is to be prescribed thyroxine. This is an artificial version of the thyroid hormone T4 and is aimed at boosting levels to “charge up” the thyroid. Many people report feeling better fairly quickly, whilst others do not. This is a classic example of the biological differences of each person and there are many factors to consider.

Much of the conversion of the thyroid hormones occurs in the liver. So diet and lifestyle choices that may impact or impair the liver’s function may be an underlying issue that needs to be addressed.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is becoming increasingly common as society over consumes carbohydrates and sugar-laden foods and beverages. Sugar that cannot be adequately burned by the body is readily stored as fat and the liver takes on much of this burden, which in-turn reduces its efficiency.

Medication can not undo the woes of a poor diet. If the thyroid is responsible for the energy the human body produces then there is no point fuelling it with rubbish. The diet needs to be massaged to swing in the favour of plant-based food forming the bulk of the diet, supported by good fats and lean (preferably organic) meats. The body also needs to be adequately hydrated to help circulate the nutrients from the food around the body, so reaching for water, particularly in place of the sugary or energy drink choices as a crutch to the ongoing fatigue, is a must.

Though thyroxine is the first-line medical treatment for thyroid, there is in fact many other modifiable factors. A doctor with an integrative or functional approach or a naturopath, nutritionist or herbalist have a lot of expertise on the lifestyle, dietary, nutritional and herbal interventions for optimising thyroid function.

Conclusion

Bottom line, there are likely thousands of people suffering needlessly with the effects of poor thyroid function. Your health is your best personal asset, so listen to your body, take a look at the symptoms you’re currently living with and ask yourself whether your thyroid might be part of the problem. Checking basal temperature and noting any symptoms might be the first step you need to opening up this conversation with your healthcare professional.

References:

- Schubert, A. Side effects of mild hypothermia. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 1995;7(2). [Full Text]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Year Book Australia, 2012. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra: 24 May 2012. [Link]

- O’Leary PC, Feddema PH, Michelangeli VP, et al. Investigations of thyroid hormones and antibodies based on a community health survey: the Busselton thyroid study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64(1):97-104. [Abstract]

- So M, MacIssac R, Grossman M. Hypothyroidism: investigation and management. Austr Fam Phys 2012;41(8):556-562. [Full Text]

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.