Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are relatively common in women, occurring when urinary pathogens from the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) or vagina colonise the periurethral (tissue surrounding the urethra) mucosa and reach the bladder.[1]

Anatomy is a key reason for the greater risk in females, due to a shorter urethra when compared to males, and easy colonisation of the periurethral zone by intestinal bacteria.[1]

From 25-50% of women have at least one episode of UTIs in their lives, and of these, 27% have a relapse during the six months following the first infection, while approximately 3% have two relapses during the same period.[1]

Symptomatology includes frequent and intense need to urinate and burning and/or pain on urination. The urine is often cloudy, sometimes even pink due to the presence of blood.[1]

Approximately 90% of acute UTIs are caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. E. coli’s ability to adhere to the periurethral area and thus ascend the urinary tract appears to be essential for it to colonise, persist in and infect the urinary tract.[1]

Methods of infection prevention thus focus on inhibiting these adhesion properties.

E. coli use appendages referred to as ‘fimbriae’ to adhere to the urinary epithelium:

- Type 1 fimbriae: bind to mannose receptors of the urinary tract

- P fimbriae: mannose resistant; bind to globoseries glycosphingolipids.[1,2]

Cranberry extract for UTI prevention

Evidence supports the use of cranberry as a means of preventing E. coli adherence to the urinary tract. Cranberry’s anti-adhesion properties appear to be attributed, in part, to the presence of A-type proanthocyanidins (PACs), which block the binding of E. coli P fimbriae, and also fructose, which blocks the binding of type 1 fimbriae.[1]

A new player on the cranberry market now delivers extracts standardised not only to PACs, but also minimum levels of E. coli anti-adhesion activity (AAA), provided by a unique combination of active cranberry phytochemicals in addition to PACs and naturally occurring fructose.[3]

Despite the evidence supporting cranberry use as a means of preventing E. coli adherence and overgrowth, its potential for treating an active infection has not yet proven to be significant. For this reason, cranberry may work best prophylactically in individuals aware of their susceptibility to infection (i.e. past infections).

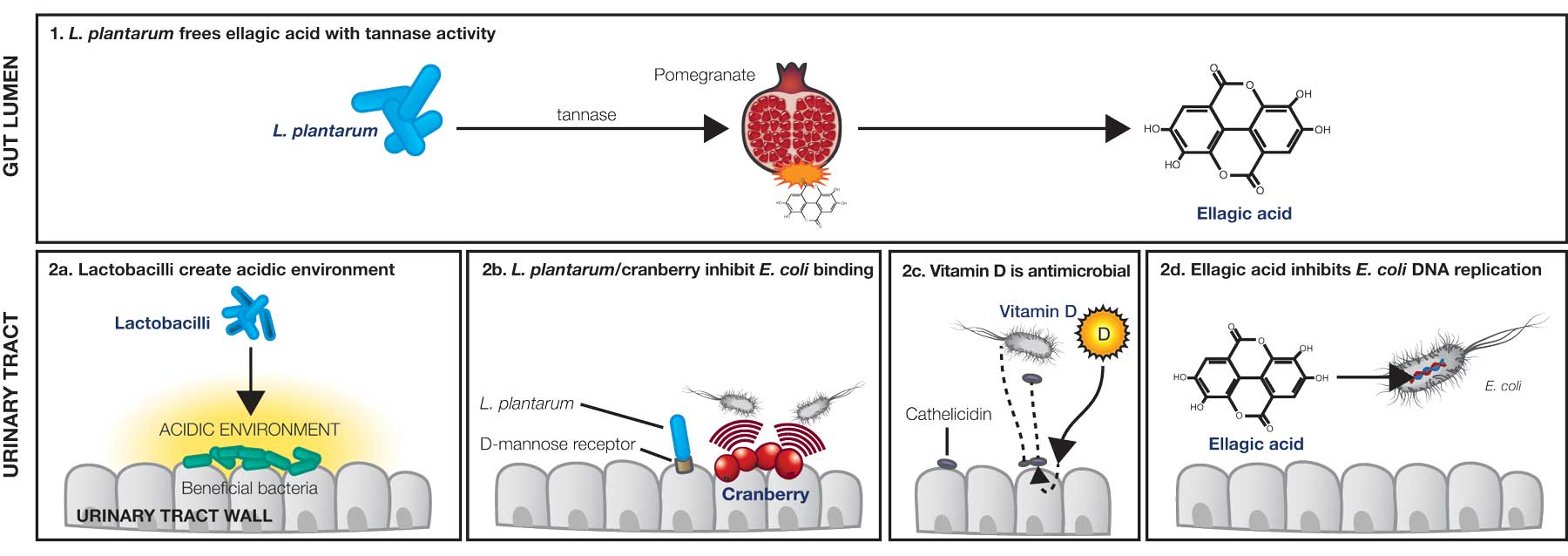

Additional interventions are suggested to provide support for improving the eradication of an active infection, and these include ellagic acid from pomegranate, vitamin D and lactobacilli species which naturally inhabit the urogenital tract.

Ellagic acid – a natural antibiotic

Ellagic acid from pomegranate appears to function in the same manner, and at a similar potency, when compared to quinolone antibiotics (e.g. nalidixic acid, moxifloxacin), commonly prescribed for UTIs.[4]

Ellagic acid’s mechanism of action against E. coli is via suppression of bacterial reproduction by inhibiting the DNA gyrase enzyme required for bacterial replication. DNA gyrase is an essential bacterial enzyme that catalyses the introduction of negative superhelical turns into closed-circuit double-stranded DNA. Put simply, without gyrase function, a cell cannot replicate.[4]

Ellagic acid also holds antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and in vitro evidence has demonstrated ellagic acid from pomegranate to be effective against additional pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans, preventing biofilm formation and inhibiting growth. Interestingly, ellagic acid was able to disrupt pre-formed biofilms of C. albicans, a trait that makes substances beneficial in reducing pathogen virulence and assisting in the treatment of more stubborn infections.[5]

Pomegranate standardised to an ellagic acid content is therefore considered a worthy natural option in treatment and prevention of E. coli infections.

One limitation, however exists in the requirement of active ellagic acid to be yielded from pomegranate, as this process requires hydrolysis of the ellagitannin and punigalagin (found in pomegranate). Specific microorganisms which inhabit the GIT are identified as exerting the tannase activity required for this hydrolysis, and ultimate release, of ellagic acid. Lactobacillus plantarum is one such species which has been found to exert tannase activity,[6] resulting in what may be referred to as a synergistic relationship between L. plantarum and pomegranate in terms of maximising the potential of pomegranate as an intervention for infection.

Further to the tannase activity within the GIT, beneficial microbes inhabiting the mucosal areas of the body function in a number of additional ways to assist in the prevention and treatment of pathogenic overgrowth. L. plantarum has a great capacity to bind mannose receptors, enabling its ability to attach to the urinary epithelium and competitively inhibit E. coli growth.[7] Furthermore, beneficial microbes inhabiting the urogenital tract function to prevent pathogenic overgrowth via additional mechanisms including lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide production,[8] and stimulation of local immune function (e.g. enhanced secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) production). Probiotic species such as L. plantarum have even demonstrated usefulness against multi-drug resistant uropathogens such as E. coli.[8]

Vitamin D for mucosal immune function

The role of vitamin D in preventing infection must also not be overlooked. Apart from its well-known task to regulate calcium metabolism, vitamin D has been recognised to influence innate and acquired immune reactions,[9] and vitamin D stores may influence susceptibility to urinary tract infection in selected individuals.[9]

Evidence demonstrates vitamin D to stimulate the body’s endogenous antimicrobial defence system in the urogenital tract (as well as respiratory epithelium and keratinocytes).[9] Specifically, vitamin D3 is involved in activating cathelicidin (an antimicrobial peptide) production in the urinary tract and bladder epithelia when exposed to pathogenic bacteria. Cathelicidin plays a fundamental role in the body’s first line of defence against infection, attacking uropathogenic cell membranes.[9,10]

Understanding the wide-spread incidence of vitamin D deficiency in Australia, it should be considered as a potential contributing factor when patients report frequent infections at mucosal sites of the body (e.g. urogenital and respiratory tracts).

Natural interventions for UTIs: Mechanisms of action

Conclusion

In conclusion, cranberry extracts standardised to PAC and anti-adhesion activity (AAA) represent promising interventions for the prevention of UTIs, whilst vitamin D, ellagic acid (from pomegranate) and specific lactobacilli species provide noted benefits for both infection prevention and treatment.

Addressing additional dietary and lifestyle factors which may be influencing infection risk is fundamental to supporting patients suffering persistent or chronic urinary tract and/or bladder infections. Staying well hydrated, avoiding excess dietary sugar, urinating soon after intercourse, and using the right wiping technique (front to back) after using the bathroom should also be encouraged, as should stress management. Chronic mis-managed stress may play a role in suppressing healthy immune function (e.g. seeing depletion in sIgA), and may see a reduction in mucosal immunity.[11]

References

- Nicolosi D, Tempera G, Genovese C, et al. Anti-adhesion activity of A2-type proanthocyanidins (a cranberry major component) on uropathogenic E. coli and P. mirabilis strains. Antibiotics (Basel) 2014;3(2):143-154. [Full text]

- Melican K, Sandoval RM, Kader A, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli P and Type 1 fimbriae act in synergy in a living host to facilitate renal colonization leading to nephron obstruction. PLOS 2011;7(2):e1001298. [Full text]

- Howell A, Souza D, Roller M, et al. Comparison of the anti-adhesion activity of three different cranberry extracts on uropathogenic P-fimbriated Escherichia coli: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, ex vivo, acute study. Nat Prod Commun 2015;10(7):1215-1218. [Abstract]

- Weinder-Wells MA, Altom J, Fernandez J, et al. DNA gyrase inhibitory activity of ellagic acid derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1998;8(1):97-100. [Abstract]

- Bakkiyaraj D, Nandhini JR, Malathy B, et al. The anti-biofilm potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) extract against human bacterial and fungal pathogens. Biofouling 2013;29(8):929-937. [Abstract]

- Osawa R, Kuroiso K, Goto S, et al. Isolation of tannin-degrading lactobacilli from humans and fermented foods. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000;66(7):3093-3097. [Full text]

- Gross G, Snel J, Boekhorst J, et al. Biodiversity of mannose-specific adhesion in Lactobacillus plantarum revisited: strain-specific domain composition of the mannose-adhesin. Benef Microbes 2010;1(1):61-66. [Abstract]

- Manzoor A, Ul-Haq I, Baig S, et al. Efficacy of locally isolated lactic acid bacteria against antibiotic-resistant uropathogens. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2016;9(1):e18952. [Full text]

- Hertting O, Holm Å, Lüthje P, et al. Vitamin D induction of the human antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in the urinary bladder. PLoS One 2010;5(12):e15580. [Full text]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides, innate immunity, and the normally sterile urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2810-2816. [Full text]

- Fan Y, Tang Y, Lu Q, et al. Dynamic changes in salivary cortisol and secretory immunoglobulin a response to acute stress. Stress Health 2009;25:189-194. [Abstract]

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.