In most countries, healthcare and welfare systems are legal pyramid schemes; that is, lots of young, healthy people have to pay in at the bottom, so that the few old, sick people can take out at the top. But what if the young people are too sick to have jobs to pay in? What if they’re so sick they’re taking out? Without a solid foundation, the whole pyramid collapses.

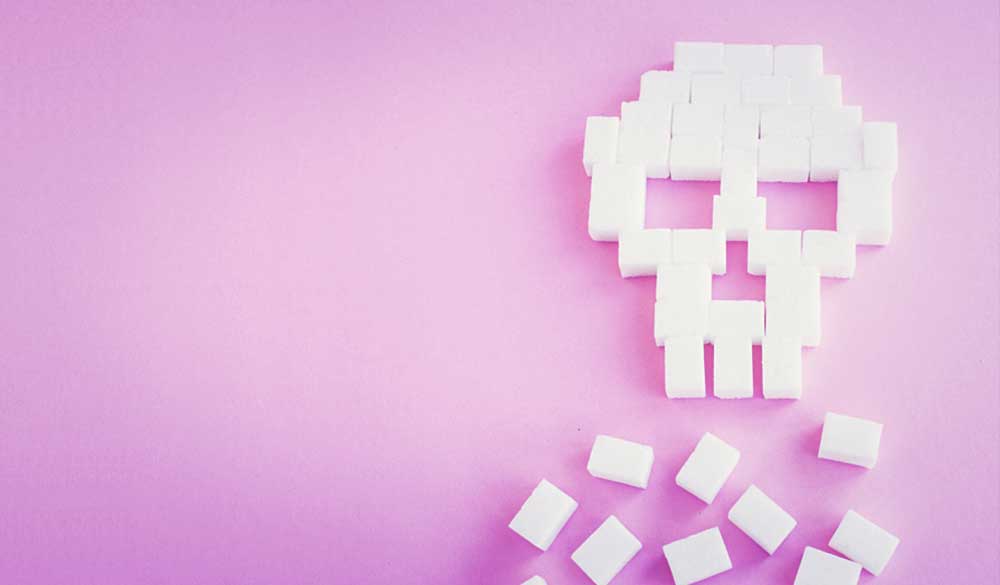

Sugar is causative for metabolic syndrome, unrelated to calories or weight gain

And that is what we are experiencing today. Children are the canaries in the coal mine. When they manifest increased rates of adult diseases like hypertension or high triglycerides, something’s wrong.[1] And when they get diseases that had never previously been seen in children, like type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease,[2] it’s time to re-evaluate.

Where could these diseases come from?

Everyone assumes this is the result of the obesity epidemic – too many calories in, too few out. Children and adults are getting fat, so they’re getting sick. But there are three reasons to challenge this assumption:

- Certain countries are obese without being diabetic (e.g. Iceland, Mongolia, Micronesia), while other countries are diabetic without being obese (e.g. India, Pakistan, China).[3,4] China has 12% diabetes, and they’re not fat;4 the USA is the fattest nation on earth, and the diabetes prevalence is only 9%.

- Obesity is increasing globally at 1% per year, while diabetes is increasing globally at 4% per year. If diabetes were just a subset of obesity, how can you explain its more rapid increase?

- While 80% of the obese population is metabolically ill, that means 20% are not. Conversely, 40% of the normal weight population harbours these same diseases. If normal weight people get them, how is this related to obesity? Indeed, we now know that obesity is a marker rather than a cause for these diseases, termed “metabolic syndrome”.[5]

So what causes metabolic syndrome?

Everyone assumes it’s the burden of our consumed calories in total; no one specific food causes it, because “a calorie is a calorie”. Yet our group at UCSF has provided the proof that relegates this thesis to the dustbin of history. We studied 43 Latino and African-American children with obesity and metabolic syndrome over a 10-day period. We assessed their metabolic status on their home diet. And then, for the next nine days, we catered their meals – NO ADDED SUGAR. We gave them the same calories and protein and fat content as their home diet. We gave them the same percentage of carbohydrate; however, we substituted starch for sugar. We took the chicken teriyaki out. We put the turkey hot dogs in. We took the sweetened yogurt out. We put the baked potato chips in. We took the donuts out. We put the bagels in. We gave them unhealthy processed food, but it was NO ADDED SUGAR food. We gave them a scale to take home. If their weight was declining, we made them eat more. Then we studied them again.

In short, every aspect of their metabolic health improved, with no change in weight. Blood pressure, triglycerides, low density lipoprotein (LDL), insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance all improved, and on the same number of calories and without weight loss, just by removing the added sugar – and in just 10 days![6] Furthermore, their cardiovascular risk factors disappeared into thin air.[7]

This study demonstrates categorically that, “a calorie is not a calorie”, and that sugar is causative for metabolic syndrome, unrelated to calories or weight gain. Sugar may not be the only cause, but it is by far and away the easiest cause to avoid. Kids could improve their metabolic health – even while continuing to eat processed food – just by dumping the sugar. Can you imagine how much healthier they’d be if they ate real food?

But isn’t sugar natural?

The naysayers will say, “But sugar is natural. Sugar’s been with us for thousands of years. Sugar is FOOD! How can food be toxic?” This begs the question: What is food? Is sugar food? Webster’s Dictionary defines food as “material consisting essentially of protein, carbohydrate, and fat used in the body of an organism to sustain growth, repair, and vital processes and to furnish energy”.[8] Sugar furnishes energy, so of course it’s a food!

Sugar vs. alcohol

But wait… can you name an energy source that is not nutritious, where there is no biochemical reaction in the human body (or in any organism) that requires it, that causes disease when consumed at high dose, yet we love it anyway and it’s addictive?

Answer: alcohol. It’s got calories, but it’s not nutritious. There’s no biochemical reaction that requires it, and at high doses, alcohol can fry your liver. Yet we love it anyway. Alcohol is not dangerous because of its calories. Alcohol is not dangerous because it makes you put on weight. Alcohol is dangerous because it’s alcohol. Clearly, alcohol is NOT a food. It’s not nutritious. When consumed in excess, it’s a toxin.

Same with sugar. Fructose, the sweet molecule in sugar, contains calories that you can burn for energy, but it’s not nutritious, because there’s no biochemical reaction that requires it. And when consumed in excess, sugar fries your liver. Just like alcohol.[9] And this makes sense, because where do you get alcohol from? Fermentation of sugar. Sugar causes diabetes, heart disease, fatty liver disease and tooth decay. Sugar’s not dangerous because of its calories, or because it makes you fat. Sugar is dangerous because it’s sugar.[10] It’s not nutritious. When consumed in excess, it’s a toxin.

And it’s addictive. Fructose directly increases consumption independent of energy need.[11] Sucrose infusion directly into the nucleus accumbens reduces dopamine and μ-opioid receptors similar to morphine,[12] and establishes hard-wired pathways for craving in these areas that can be identified by fMRI.[13] Indeed, sweetness surpasses cocaine as reward.[14] Animal models of intermittent sugar administration induces behavioural alterations consistent with dependence, i.e. bingeing, withdrawal, craving, and cross-sensitisation to other drugs of abuse.[15]

Sugar is just like alcohol. And that’s why children are getting the diseases of alcohol – type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease – without alcohol. But we could turn this around in 10 days – if we chose to.

Sugar is the alcohol of the child

Sugar is not food. It’s the same as alcohol. It’s an energy source, but without nutrition, with no biochemical reaction that requires it and it promotes metabolic syndrome, yet we love it anyway and it’s addictive. Sugar is the alcohol of the child. Our children are under the influence. And healthcare and welfare systems are on life support worldwide because of it.

Professor Robert H. Lustig is Professor of Paediatrics and founder of the Weight Assessment for Teen and Child Health (WATCH) Program at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital,[16] and member of the Institute for Health Policy Studies at UCSF. He is the author of Fat Chance,[17] the upcoming The Agony of Ecstasy, and he is the President of the non-profit Institute for Responsible Nutrition.[18]

References

- Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. New Eng J Med 2004;350:2362-2374. [Full text]

- Weiss R, Bremer AA, Lustig RH. What is metabolic syndrome, and why are children getting it? Ann N Y Acad Sci 2013;128(1):123-140. [Full text]

- Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, et al. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS One 2013;8(2):e57873. [Full text]

- Chan JC, Zhang Y, Ning G. Diabetes in China: a societal solution for a personal challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2(12):969-979. [Abstract]

- Bremer AA, Mietus-Snyder ML, Lustig RH. Toward a unifying hypothesis of metabolic syndrome. Pediatrics 2012;129(3):557-570. [Ful text]

- Lustig RH, Mulligan K, Noworolski SM, et al. Isocaloric fructose restriction and metabolic improvement in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2016;24(2):453-460. [Full text]

- Gugliucci A, Lustig RH, Caccavello R, et al. Short-term isocaloric fructose restriction lowers apoC-III levels and yields less atherogenic lipoprotein profiles in children with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2016;253:171-177. [Abstract]

- Food. Viewed 4 November 2016, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/food

- Lustig RH. Fructose: it's “alcohol without the buzz". Adv Nutr 2013;4(2):226-235. [Full text]

- Lustig RH, Schmidt LA, Brindis CD. Public health: the toxic truth about sugar. Nature 2012;482(7383):27-29. [Abstract]

- Lindqvist A, Baelemans A, Erlanson-Albertsson C. Effects of sucrose, glucose and fructose on peripheral and central appetite signals. Regul Pept 2008;150(1-3):26-32. [Abstract]

- Spangler R, Wittkowski KM, Goddard NL, et al. Opiate-like effects of sugar on gene expression in reward areas of the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2004;124(2):134-142. [Abstract]

- Pelchat ML, Johnson A, Chan R, et al. Images of desire: food-craving activation during fMRI. Neuroimage 2004;23(4):1486-1493. [Full text]

- Lenoir M, Serre F, Cantin L, et al. Intense sweetness surpasses cocaine reward. PLoS One 2007;2(8):e698. [Full text]

- Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008;32(1):20-39. [Full text]

- Robert Lustig, MD. Viewed 4 November 2016, http://profiles.ucsf.edu/robert.lustig

- Lustig RH. Fat chance. Plume: New York.

- Alderson W, Lustig RH. Real food impact campaign. Viewed 4 November 2016, http://www.responsiblefoods.org/

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.