Read the media headlines and research

BMJ Journals

Hypersensitive adverse drug reactions to glucosamine and chondroitin preparations in Australia between 2000 and 2011

Sydney Morning Herald

'Not helpful, can be harmful': Doctors issue glucosamine pill warning

The Age

'Not helpful, can be harmful': Doctors issue glucosamine pill warning

Recent media attention would have us believe that the use of glucosamine supplements is ineffective and harmful, and that the risks outweigh any benefit.

In this episode, our FX Omics and FX Medicine podcast hosts, Dr Mark Donohoe and Andrew Whitfield-Cook, join forces to examine the story that hit headlines sensationalising the outcomes of one particular study which urged patients to stop taking their glucosamine products. Andrew and Mark expertly take us through a balanced look at the scientific evidence for glucosamine, the adverse event reporting and demonstrate why it's important to seek considered clinical advice from a qualified health professional.

COVERED IN THIS EPISODE

[00:40] Welcoming Andrew Whitfield-Cook

[01:15] Adverse effects of glucosamine - what the data truly shows

[04:44] Friends of Science in Medicine and study bias

[06:37] Comparing the data: adverse effects of glucosamine vs ibuprofen

[08:13] Were the adverse reactions reported statistically significant?

[10:50] Side effects of glucosamine and how source is a factor

[13:17] Potential reasons of gastrointestinal side effects unrelated to glucosamine itself

[15:06] Why the study could be harmful to patients

[16:43] Problems with the study design

[20:06] Why type of glucosamine matters

[25:58] Responsible treatment of osteoarthritis

[27:44] Conclusions

Mark: Hi everyone and welcome. I'm Dr. Mark Donohoe, and today I'm in the unusual position of being in the FX Medicine chair to address a breaking issue playing out in Australia about adverse reactions to glucosamine. It's made headlines in major news outlets telling the public that glucosamine "doesn't work and could cause harm." Our usual host, Andrew Whitfield-Cook is joining us on the line. Hi, Andrew, how you going?

Andrew: Really well. Thanks, Mark. How are you? It's very different to be on the other side of the microphone from FX Medicine.

Mark: Andrew, this kind of is a bit of a surprise to me, I've got to say. Last week, and we're to talking, you know, February 2020, last week a patient came in and said, "I've come off by glucosamine." “Why is that?" “Oh, the Sydney Morning Herald article told me that I should come off my glucosamine. And it doesn't work and it's very, very dangerous." And I thought, “Hmm, that's something that's strange because in years of work with glucosamine for many, many patients, I never heard of anything very dangerous happening." I got a bit of reading around and finally tracked down the paper. It's one that was carried out of Adelaide, and we'll go into the authors a little bit later, it seemed an innocuous paper that became a flashpoint for no particularly good reason. From what I can see about 350, 400 adverse effects over 11 years for a very commonly used agent that provides a lot of relief for the symptoms and arguably is far better for you than any potential adverse outcome. So I can't see what was going on. If you study anything for adverse reactions and enough people use it, if there's a million people using anything, sugar pills, you going to have more than 300 adverse reactions. So...

Andrew: That’s right. That's exactly right.

Mark: ...do you have any thoughts about that, about the provenance of that paper and why we should even be talking about it?

Andrew: Well, look, I think it's interesting that any bad media about a supplement is very quickly taken up. Any good media is very quickly glossed over. Any good media about a drug is very quickly taken up, any bad media unless it results in multiple deaths, not side effects, is very quickly glossed over.

So here's my question. Has there been any media attention to the 50 deaths in the same period that they looked at using ibuprofen? No.

Mark: No.

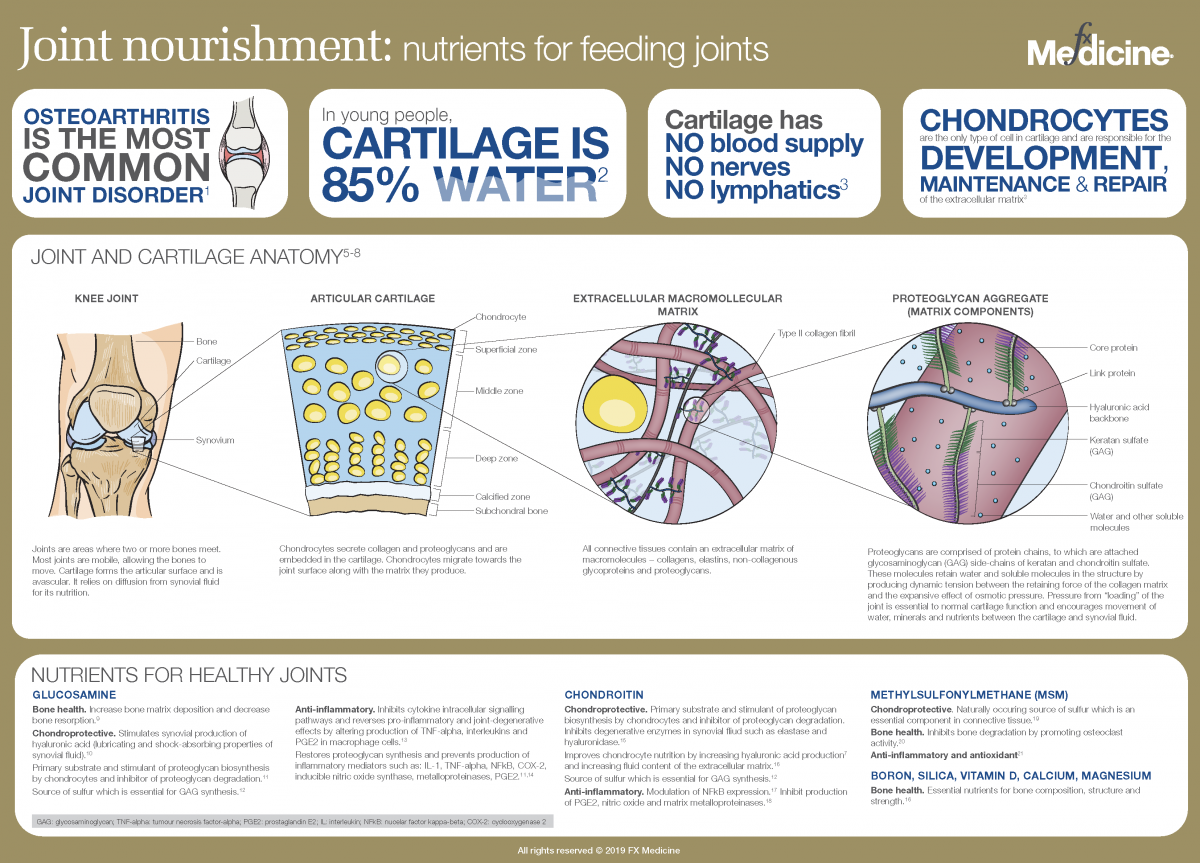

Joint nourishment: nutrients for feeding joints - INFOGRAPHIC

Joint nourishment: nutrients for feeding joints - INFOGRAPHIC

Andrew: So when you when you look at the number of case reports of glucosamine, it was something like 400. Well, there's been 400 or let's say 500. I think it's 450, 460. But let's say 500 reports, totally. And this is not between the time period, the face date, which is 2000 to 2011. Talk about that data range.

Mark: The number was 366 adverse drug reactions to glucosamine and chondroitin.

Andrew: That's right. I'm going actually from 2000 to 2019…

Mark: Right, okay.

Andrew: …which indeed is what the Drug Adverse Event Notification website, the DAEN, ranges between.

Mark: Right.

Andrew: So I have no idea why they found it appropriate to omit the previous eight years or the most recent eight years. I have no idea why they would do that. Having said that, it was something like 460 adverse events notified within 2000 to 2019, and of that there was one death and that was in 2001. The patient there was on multiple other medications including Warfarin, the death from haematuria. And so, you know, hello, interaction? Ah, yes. And we'll talk about interactions later. But when you're blaming one entity out of a concoction and like a lot of medications that they were on, it's very hard, I would say unethical to point the finger at one, indeed the supplement.

Mark: What you just told me raises an alarm bell, and that is if there were 366 ADR, adverse drug reactions, in that 11-year period, only a further 100 in the 9 years following, the question is always “why would a research group choose a cut-off date after which things appeared to get better?” It looks almost like data mining of how do we get the most bang for our buck if we're looking for adverse reactions? Cut it off before the time that the adverse reactions appear to be reported less frequently, and that gives you a bigger number.

And the reason I wonder about that, at least one of the authors is a professor, very well respected professor, but again, a board member of the Friends of Science in Medicine. Now, the Friends of Science in Medicine do have a history of going through this, of looking at alternative, complementary, non-orthodox drugs and having a very razor-sharp focus on those things. Looking to say, "Well, maybe they need to be limited, banned or anything else."

My view is you can't have those preconceptions, be on the board and then say, "But I have no fight against complementary medicine." If you're part of the board, you've got to at least own up to that in the paper and say, "This is my prior position. I have a position in a group that say that complementary medicines are worthless, they don't have any part to play in medicine. This paper doesn't come out of the blue."

So I think, even the acknowledgement to say, "Look, I'm on the board of the Friends of Science in Medicine. Let's get that out of the way. Now get on with the paper." So it leaves a bad taste of why 2000 to 2011? What about one of the authors and whether there was a predisposition to wanting to look for adverse reactions, even if they are not important and should not change anything to do with our prescribing patterns?

Andrew: I think one of the points that you raise there has also got to do with when you're looking at how many cases were reported, you've always got to compare it to how many cases were there of patient episodes of people taking the medicine.

Mark: Yes.

Andrew: So, for instance, I'm looking at these results here from ibuprofen from 2000 to 2019, there was 1,216 reports, 819 of which were suspected as being the single medicine, and 50 deaths. Now when you take into account the amount of ibuprofen medications and doses that were taken throughout that period, you think, "Okay, you know, look, it's, it's unfortunate, but it's also not very big."

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: Hang on. Let's look at glucosamine. A recent paper published in BMJ on 466,000 patients, it's an observational study, so I concede that. They noted one fifth, 20% of participants use glucosamine sulfate.

Mark: Right.

Andrew: So we're talking about, you know, let's say, 100,000 people there, and where are the side effects in that trial? Virtually nil. So it's really interesting how when you go back just a few years, say, you know, to 2008, 2012, even 2014, the papers all over the world, virtually say, "Side effects were very few and they were mainly around the rash, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, urticaria." That sort of...

Mark: Which are important, right? We should be clear it's important that we do notice the adverse reactions from anything.

Andrew: Oh, absolutely.

Mark: Placebos have typically around about the same rate of adverse reaction.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: So when you get sugar pills in a study, the adverse reaction rates are approximately at the same level that glucosamine is in this study, right? You are right though. The missing information is how many people are taking glucosamine? So, if we say, what is it, that 35 adverse drug reactions per year. If there's only 2,000 people taking it, that's massive. If there's two million people taking it, that's indistinguishable from no reaction whatsoever.

Andrew: Absolutely. Yeah. That’s right.

Mark: And so careful that you don't just publish a paper which says 366 people. That's terrible. It's not terrible if the alternative was those numbers of people were taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatories with a far higher likelihood of adverse reaction and death rates.

Andrew: That’s right.

Mark: So we need to compare apples with apples and we also need to have if you like almost a placebo control in this of let's do adverse drug reaction reports to the TGA of people taking placebos. It's difficult one to organise.

Andrew: I don't know how you do that one.

Mark: I know but there is going to be a rate. Every time a pill goes into person, there's the capsule of the pill, there's the fillers, there are always things that go on and you're putting something on the stomach. So getting many of the adverse reaction rates, I just, as a doctor think, look at this and say, "Look, this is really say one to two million Australians are taking glucosamine, this is such a low adverse reaction rate,” that the real story should be “what an extraordinarily low adverse reaction rate compared to the alternatives for arthritis?” Not, “this is a big number, and shouldn't we pay more attention to it?” So one issue is how what's the rate of adverse reactions?

Andrew: That’s right.

Mark: The second thing is what's the alternative, what's the drug therapy safer than this? And if the drug therapy was safer and as effective or more effective, then you've got a story. But when the drug therapy, as every GP knows, is a risky drug therapy that we now have to give acid suppressants to try and stop gastrointestinal bleeding, then I don't think that this is a balanced weighing up of what an adverse reaction is and whether these are significant, whether they have any impact on what we would prescribe in practice. My take on it is this is like raising flags and saying, "Glucosamine is terrible." No thought about is it the right glucosamine, the wrong glucosamine? No thought about details, just numbers appear on a page and the media take it up, and someone has to promote that to the media. This was not media worthy. This is nothing.

Andrew: No. So I'm just going on about these adverse effects and there was a very interesting pamphlet, if you like, from...it's Medicines Question and Answers Q&A's, from the NHS in Britain, that's UK, obviously, on glucosamine, what are the adverse effects? And like it lists everything there, mainly the urticarias, mainly the epigastric tenderness, constipation, diarrhoea, heartburn, vomiting, all of the usual ones that you can see with placebo. But I do concede that there has been in the past a certain risk with those people who have shellfish allergy…

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: …because the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia has mandated previously that all glucosamine chondroitin products be of a seafood origin. Now that's changed recently. So it'll be interesting if you take out, let's say, the last two or three years, so let's say going back to you know 2017, and look at the side effects there compared to the side effects reported in the following years. That would be a very interesting thing to look at.

Mark: And that would be useful science to do as well. If you change the origin of... The paper does say probably it's the meat contamination on the shellfish. You know, the shell obviously does not have the antigens that are significant in shellfish allergies.

Andrew: That's right.

Mark: But if it is a fault in manufacturing, that is valuable information to know.

Andrew: That’s right.

Mark: And if a change of the origins from shellfish to bovine or any other source of glucosamine, if that's associated with a significant drop, then good can come from even a paper like this. But I still come back to the question of is this rate of 34 adverse reaction reports a year, none of which were typically severe, the majority of them were very mild and every, every doctor knows, again, you give tablets to a person, everybody has the potential to react to a tablet. So I don't see it as being good science at the moment, but this may form a basis to say, "Look, potential for hypersensitivity shellfish meat allergy." One issue might be better manufacturing processes to ensure that there is no meat contamination of the shell before production, and the other one would be maybe a move away from shellfish is the safer option. And we will find that out with adverse reaction rates over the past three years as compared to the previous years.

Andrew: Yeah. And, you know, one of the other useful things as well as is when you consider that many preparations, not all, but many preparations are in capsules.

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: If that person might have say a sliding hiatus hernia, if the capsule might break open earlier and you might have some reflux, it has happened, indeed it's happened to me, where you get a burp powder coming out your mouth.

Mark: Right.

Andrew: Now let's say that was glucosamine chondroitin, that might be inhaled, and you might have a local reaction in the lungs from that. So there is that, albeit very small, there is that risk, and I mean, that's been noted with psyllium husk in inhalation. So you can get a local reaction from inhalation of any powder. Rare? Yes.

Mark: Andrew, you can get a local reaction from burping. I can definite, I mean, it's part of what we doctors think of every time, a little bit of reflux, burping up a bit of acid is probably is bad as that. But it does give you a bit of a perspective that since many of the adverse reports were gastrointestinal, upper gastrointestinal reactions…

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: …that anything that's encapsulated, anything where a bit of acid reflux can be induced, swallowing a damn capsule or swallowing a pea, can do exactly the same thing, that if you get a bit of a burp and it's acidic and it has the potential to irritate the upper throat, the oesophagus, then you can get GORD-like symptoms. And so I don't see that specifically have any relationship to the glucosamine as the kind of active ingredient of it, I think of that as more a capsule risk that happens occasionally and, you know, people get stuck in the throat. My own wife has done that last week of swallowing a capsule, feeling it stuck and feeling the throat is burning.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: So I'm not against people trolling over adverse reactions. I think it's good to know where the problems arise.

Andrew: I think it’s great. Yeah.

Mark: I think the problem is that it can induce panic where there is no panic to be had, and a valuable therapeutic agent has people stopping it without asking their practitioners for a bit of perspective on all of this.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: But the downside for me would be if people stopped their glucosamine, go back on their ibuprofen or their non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, and they do that without acid suppression and without doctor's advice, there's more harm can come from this paper and the kind of sensational reporting of it, then good. That this should have been something that deposits in the medical literature, we all go back and consider it. We think of it rationally. Could bovine replace crustacean, is there evidence of meat attached to the crustacean shell? Is one brand doing something dodgy? Those kind of questions are good questions. But they're not paper, newspaper headlines, whereas this has gone outside the safety area that I would say is doing harm. My patient has come off glucosamine believing it to be terribly harmful. When her arthritis starts to flare up again, I know what will happen. She'll go for something, and that something is likely to be the non-steroidal that is still sitting on her shelf, which she hasn't used for the last year because of the glucosamine.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: So that's my concern is this is not the way to deliver science. This is sensationalised and we'll get people to put themselves in harm's way not to stay well.

Andrew: Yeah. But there remains a few questions. I mean, one is why that data subset? Why 2000 and 2011, not including 2019 when it's freely available?

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: You just go to the DAEN and there they are. You can do various lists. You can look at what medications the people who had the adverse effects were on as well. So, for instance, in the one death that was reported in 2001, the patient was also on warfarin, on steroids and things like that. So there's potential in interactions there when you're looking at glucosamine, which is a GAG, glycosaminoglycan with warfs. There is that potential. And I think in this patient subset, you've got to really monitor them closely.

Mark: That was a decade where warfarin was commonly used…

Andrew: Yes.

Mark: …and use has disappeared largely over the last few years with Apixaban and...

Andrew: You've also got the potential interaction with anti-diabetic medications. And this is not well studied at all, but I think it requires vigilance. And if anybody sees a definite trend, preferably with use withdrawal and re-challenge, on the effects with HbA1c or blood sugar levels, then, okay, report that.

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: But the problem is when you get people saying, "I have diabetes and I've had it for 10 years. I took glucosamine and yesterday my blood sugar went up."

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: We’ve got to take out the, what people always think they see as the immediate thing that they just took, rather than what's happening with their disease process.

Mark: So the paper does mention that very specifically, beyond the hypersensitivity reactions, nine reports in 11 years of blood glucose increased.

Andrew: Nine.

Mark: Nine in 11 years. That is indistinguishable from zero, seriously.

Andrew: Yeah. And again, this NIH document discusses this.

Mark: We have two million people with type 2 diabetes, and we've got 400,000, I believe, with type 1 diabetes, but this is type 2 diabetes. The medications Metformin, glucoside, and the biphasic isophane insulin, they're talking about things which are very, very commonly prescribed. And if enough people are taking a GAG, it is plausible, but there will be a loss of blood sugar control or maybe temporary, or it may be longer term.

Andrew: That’s right.

Mark: And it's worth looking at, but that's a starting point rather than saying...the authors say, "Well, there is little evidence for any effect of glucosamine on blood sugar levels. We should think about it."

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: So if there's no evidence, why would you mention it rather than just say, "Here's a trial to decide whether people who are on anti-diabetic medications have alterations of blood sugar." That's a separate trial. It's a simple enough one to do. I'm sure Ian and his colleagues will be able to do that at Adelaide University and give us an answer within a couple of years.

Andrew: Secondly, I was mentioning the NIH, and it wasn't. It's the NHS of the UK. So we'll put all of these references everything that we can up on the FX Medicine website for everybody to look at and learn from because there's some just some crucial points here that can be extracted.

Mark: There are. I'd like to drag you back a little bit. Andrew, back in 2006, the British Medical Journal published the glucosamine chondroitin arthritis interventions commonly known as the GAIT trial.

Andrew: GAIT, yes.

Mark: It gained a reputation saying, "Well, celecoxib works and glucosamine doesn't work and we've settled that.” Now in the same year, the Europeans ran the glucosamine, the GUIDE trial, which did show in effect with a different form of glucosamine. I don't see any mention of the type of glucosamine in the paper that we're talking about with adverse reactions.

Andrew: It's really frustrating to me when what is said is this, "glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate," the inference to most practitioners of natural medicine would be that it's glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate.

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: Indeed it's not in the GAIT trial. It's glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate. And even, in the same New England Journal of Medicine edition, but he pointed out that this is always said, it's always brushed over, but there's more to this.

Mark: Sure.

Andrew: Like, when you think about what would be the proportion of those participants experiencing 20% or greater decrease in pain in the WOMAC score, which is the gold standard of pain scoring…

Mark: Right.

Andrew: …celecoxib was 70%, placebo was 60%, only 10% behind. Now here's the here's the rub. In the moderate to severe pain group, the glucosamine chondroitin combination achieved that same 20% reduction in 79%.

Mark: Yeah. I remember the controversy though. They did the trial and placebo was 60.1% which surprised everybody. You know, osteoarthritis, the placebo got 60% of people with a 20.1% macro reduction. Celecoxib was 70% or 70.1%, and glucosamine and glucosamine plus chondroitin sulfate was 66.6%.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: It’s one of those trolls where the P equals 0.05 became the magic dividing line and it's just between the two of them so that there was only a tiny difference between celecoxib and glucosamine and chondroitin, but it was dwarfed by the placebo effect.

Andrew: Yeah.

Mark: Absolutely dwarfed. Most doctors looked at that and said, "That's impossible. Placebo can't do as well as celecoxib," forgetting all about glucosamine.

Andrew: Yes.

Mark: What the authors did was they had subsetted it to what were the WOMAC score reductions and what was the severity of arthritis. And what they said there was in severe arthritis, the placebo response was 54%. You would expect it to be lower because it's severe arthritis, because celecoxib was 69% and glucosamine plus chondroitin sulfate, 79%.

Andrew: Now that's in the moderate to severe group. So that's subgroup.

Mark: Yeah, that's the subgrouping, and that was where all of the controversy arose…

Andrew: That’s right.

Mark: …that the journal and many of the pharmacologists in there said, "Don't subset it. You can't subset it," rather than saying, "Well, that's interesting if the most severe group, which is still a very large group, gets the better response."

Andrew: So this was the work of Daniel Clegg, was at the University of Utah, and like he did the subset analysis and pulled out that it's in the moderate to severe pain group that the glucosamine chondroitin worked. In the mild pain group, glucosamine and chondroitin didn't work. Now, here's the practical thing for me for the clinicians. In those people that have got moderate to severe arthritis, they are probably going to need the use of some pain relief.

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: And that may or may not be celecoxib. It may be one of the other inserts. It may be the paracetamol-type formulations. But wouldn't it be great to have something that didn't just relieve pain, that actually had some effect in rebuilding joints rather than just, you know, knocking out the pain of your broken leg?

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: So this is where I think relevant, responsible co-use of these medications is really what we should be aiming for in patients, not one or the other.

Mark: And we should be very clear about what the molecule is that binds to it. So glucosamine sulfate has the additional sulfur groups and there is a good evidence of the biochemistry of sulfur playing an important part in the combination with it, and the hydrochloride probably not so much.

Andrew: Yep.

Mark: So given that the trial that found that there was benefit was glucosamine sulfate in Europe, the one that found that there was just below the pH equals 0.5 benefit was the GAIT trial with glucosamine hydrochloride. Surely the next thing should be in severe arthritis, does glucosamine sulfate act in a way that allows us to stop using more dangerous drugs for exactly the same purpose?

Andrew: Yes.

Mark: And I don't see that ever having been done. We're now 13 years down the line and it's almost like people lost interest there. And I have run into the problems with celecoxib and with all the non-steroidals, Cox-1 and Cox-2. They have a very, very high adverse reaction rate. People don't like them, they come off them, they put up with the pain rather than put up with the irritation of the stomach and the nausea. For my clinical practice, glucosamine was a godsend because if 60% are going to benefit as a placebo, I want something with all that placebo response, and if there's another 20% over the top of that for the severe arthritis, that's a bonus as far as I'm concerned.

Andrew: Well, look, we can also bring into there the responsible treatment of osteoarthritis…

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: …and the number one of course is losing weight or weight management.

Mark: Yes.

Andrew: And the other one is milder exercise within their range of moment physio, da, da, da. One of the other points that I forgot to mention with regards to diabetes, Mark, is the sad fact that I've seen, and this is mainly in retail products that have glucosamine and chondroitin in them. You're getting diabetics pulling these off the shelf with no consultation with an appropriately trained practitioner…

Mark: Yeah.

Andrew: …and, worse, that product, I've seen the number one ingredient when it was a powder, the number one ingredient was dextrose.

Mark: Right.

Andrew: So we've got to be choosing correctly formulated products.

Mark: I think that comes back to a basic, you know, concern of both of ours that if you have a medical condition and a health condition, see a practitioner, rather than self-medicate and just take, "Oh, I guess that's the same as everything else."

Andrew: Yes.

Mark: That the reason doctors and naturopaths and others do the work they do is to keep up on this and to provide you safe alternatives to medications that may be more harmful and less effective.

Andrew: Yes.

Mark: And so see your practitioner. That's what they're trained for. I do agree with you that if it's just pulling stuff off the shelf very, very frequently, even pharmacies will sell stuff that is not what was on the prescription, was not what was ordered. And I do have a sinking feeling that we need controls of what are non-prescription medicines. We need a lot tighter control so that well trained practitioners prescribe something and that is, you know, absolutely fulfilled at the chemist or wherever they go to see their practitioner.

Andrew: Yes. There's one last point as well and that is glucosamine does not go into your mouth and then fire a tube to your joints. It's metabolised by your gut.

Mark: Yes.

Andrew: And so, again, Daniel Clegg, of University of Utah, posits that we've got to look at the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glucosamine and chondroitin in the gut lining and the liver, and that may indeed play a reasonable part of their pain relieving activities. So there's a lot to be looked at here, certainly. It's not that I disregard the adverse events that were trumped. I do believe they were hyped. It's the way that it was done when you don't include the date range, the appropriate date range, when you don't include relevant study. It's the myopic approach to the news item that unfortunately has an effect on patients' health and that's where I get upset.

Mark: I get upset because in a medical practice, where control of inflammation, where control of the symptoms, minimising risk of harm to patients is a priority. We have struggled with non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and we've added acid suppressants and we've multiplied the potential for negative effects. Every doctor should pay attention to that 60% response rate to the placebo from the trial. The reason we should pay attention to it is we're not talking about compared to zero, we're comparing it to, if you and the person taking it are convinced that there is some value to what you're doing, you're halfway there, even if you're giving a sugar pill.

The last part of it is, if you've got severe arthritis, severe inflammation, or gastrointestinal inflammation, glucosamine sulfate has massive positive effects. Even this paper acknowledges that most of the people with the adverse reactions were on no other medication, and so there was no confusion about the adverse reaction. To be on no other medication is itself a win. And that's one of the points that I would make is, okay, it's true that there will be tiny numbers of adverse reactions, but compared to the alternative that we're stuck with in our medical prescribing, that's a win, not a loss. And that's what upset me about patients coming in to say, "I've stopped it because it's no good, doesn't work and it's very harmful." That is not what that paper said. And to put that out in the media and to have that circulating is a danger to my own patients. That's why I'm upset. Not from, and you know, I do get irritated when things get headlines that should never be a headline. The headline could be the other side. Tiny adverse reaction rate to glucosamine is a welcome news for all. So, it depends on how you want to word something like that.

Andrew: That's exactly right. And, of course, I think, lastly, with regards to side effect reporting, I mean, we know the side effects are way under reported. We know that we need good side effect reporting. And so we'll put the...it used to be a blue card but it's now just an adverse effect of that reporting card that's web-based and we'll put that link up on the FX Medicine website again for everybody.

Mark: I mean, the story is still in flux. The thing that's positive about the paper is they did the work to go and farm all of the information about the adverse reactions. They chose a period which is interesting to say the least, and it does look as though adverse reactions dropped off afterwards, so maybe it was designed for headlines, maybe it was just that was what they were stuck with. But we all can get the new data of the lower adverse reaction rates later.

The final thing is, report adverse reactions and have a look at them and see if we can do better. Brilliant. That's science. Scaring people for no reason is not science. It's something else and I have yet to figure out what it is in this case.

Andrew: I totally agree. And I think that sums it up very nicely, Mark.

Mark: Andrew, thank you very much. Delightful to talk with you and we'll catch up soon.

Andrew: As always. Always love chatting with you, Mark.

Additional References

Herrero-Beaumont G, Ivorra JAR, Trabado MC, et al. Glucosamine sulfate in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis symptoms: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study using acetaminophen as a side comparator. Arth Rheum. 2007 Feb; 56(2):555-567. [Full Text]

Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, Chondroitin Sulfate, and the Two in Combination for Painful Knee Osteoarthritis. New Eng J Med. 2006 Feb 23;354(8):795-808. [Full Text]

Hochberg MC. Nutritional Supplements for Knee Osteoarthritis - Still No Resolution. New Eng J Med. 2006 Feb 23;354(8):858-860. [Full Text]

Ma H, Li X, Sun D, et al. Association of habitual glucosamine use with risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2019; 365: l1628. [Full Text]

Ma H, Li X, Zhou T, et al. Glucosamine Use, Inflammation, and Genetic Susceptibility, and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective Study in UK Biobank. Diabetes Care. 2020 Jan 27[Online ahead of print]. [Abstract]

Lyon C, Mullen R, Ashby D. Time to stop glucosamine and chondroitin for knee OA? Priority Updates Res Lit (PURLs). J Fam Prac. 2018 Sep;67(9):566-568. [Full Text]

Roman-Blas J, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined Treatment With Chondroitin Sulfate and Glucosamine Sulfate Shows No Superiority Over Placebo for Reduction of Joint Pain and Functional Impairment in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Six-Month Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Arthr Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69(1):77-85. [Full Text]

Maguire E. UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists. Glucosamine- What are the adverse effects? Spec Pharm Serv. 2018 Mar. [Full Text]

Dahmer S, Schiller RM. Glucosamine. Am Fam Phys. 2008 Aug 15;78(4):471-476. [Full Text]

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.