Is dementia a normal part of ageing?

Many people think it is, but as Dr Genevieve Steiner tells us, dementia is not an inevitable part of getting older.

In this episode, Genevieve and Andrew dive deep into the complexity of dementia, exploring the use of technology (or lack thereof) to help diagnose and track its progression, the contributing factors in its aetiology such has inflammation, and why the countless drugs researchers have developed hoping for a cure haven’t yet hit the mark. They also discuss Genevieve’s exciting research on herbal interventions in the treatment of dementia and cognitive decline.

Covered in this episode

[00:45] Welcoming Dr Genevieve Steiner

[03:18] Using neuroimaging to study herbal interventions

[05:43] Assessing and diagnosing cognitive impairment

[13:37] Aetiology of Alzheimer’s

[15:52] Inflammation and dementia

[18:20] Are we reaching the peak of dementia prevalence?

[19:43] Researching a cure for dementia

[22:38] Increasing “dementia literacy” to decrease risk factors

[24:03] Are there biomarkers for early detection?

[30:22] Longitudinal studies to track progression of dementia

[33:23] Researching herbal medicines to treat dementia

[35:26] Cannabis and improving cognition

[41:56] Genevieve discusses her current research treating dementia with herbal medicines

Andrew: This is FX Medicine. I'm Andrew Whitfield-Cook. Joining us on the line today is Dr Genevieve Steiner. Her research spans the early detection, prevention, and treatment of cognitive decline in older age, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. Dr. Steiner uses neuroimaging and physiological research methods to explore the brain's function and structure to discover biomarkers and test new treatment strategies for cognitive decline with a focus on herbal medicine. She is leading the world's first clinical trial in evaluating the effect of cannabidiol on cognition in people with early-stage Alzheimer's disease. She is a Young Tall Poppy Science awardee and NHMRC-ARC Dementia Senior Research Development Fellow. She leads the NICM Health Research Institute's clinical laboratory at Western Sydney University, is president of the Australasian Society for Psychophysiology and Deputy Director of the Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research, and Enterprise, that's SPHERE. Warmly I welcome you to FX Medicine, Dr Genevieve Steiner, how are you?

Genevieve: I'm great. Thank you. Thank you very much for having me, Andrew.

Andrew: Genevieve, you have done a heck of a lot already in your career. But I've got to ask you where did your interest in herbal medicine spark?

Genevieve: That's a really good question, Andrew. And I think my interest in herbal medicine probably started back in around 2010 when I was first starting to look at research into brain function and in memory function specifically. And I came across some early work from the Swinburne Group, are you probably familiar with people like Con Stough and Andrew Pipingas .

Andrew: Scholey.

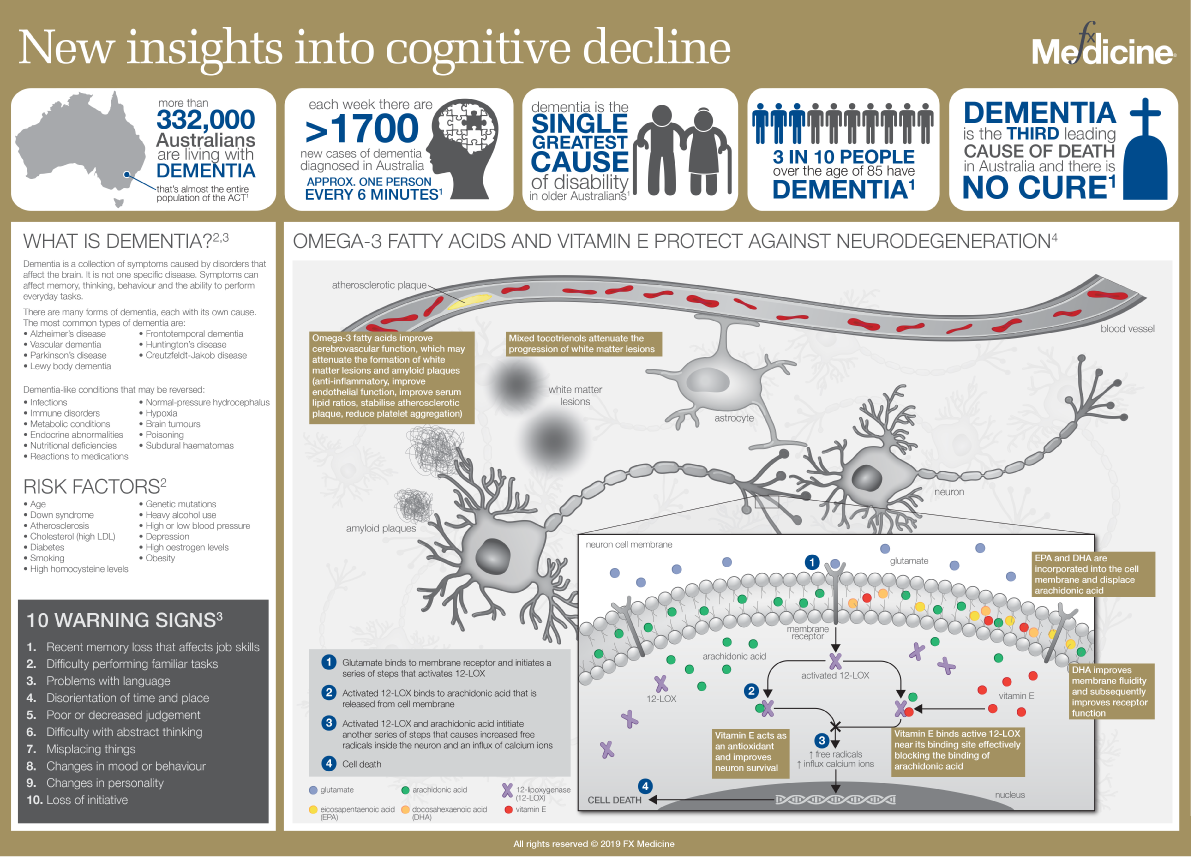

New insights into Cognitive Decline | INFOGRAPHIC

Genevieve: Yes, and Andrew Scholey, that's right, yeah. And some of the work that they were doing around brahmi. And I just found it so fascinating to see that herbal medicine could have these, what we call psychopharmacological effects on the brain. So people would take these, take some brahmi, and then they look at recording their brain function and see dramatic changes over the course of just a few hours. And that really grabbed me in quite early and I thought, "This is something I'd really like to explore for my future research career." And I guess, yeah, 10 years-ish later, here I am kind of doing something like that.

Andrew: So they've got some really neat neuroimaging machines down there and this is like they can detect changes quite rapidly upon oral administration of various therapies. So, where does this sit with regards to physiological effect and clinical effect?

Genevieve: It's a really good question. We, we're using some similar techniques at Western Sydney University. So we record EEG, electroencephalography, which is basically looking at the neural activity of the brain. And it allows you to image the brain or even look at the brain's function down to millisecond accuracy. So what you're asking about is this intersection between what's going on in the brain and these rapid brain changes that you can see after just a few hours, and how that's actually associated with cognition and...

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: ...I think what it does is it's interesting because, you know, over the years, the ways of measuring changes in our memory and thinking has really evolved quite rapidly in the last 10 to 20 years. We used to always just do things on pen and paper testing. So you can think about your sort of standard IQ tests that you might have been given, you know, 10 or 20 years ago where you just sit down and fill out this form and paper and someone might be timing you with a stopwatch. But nowadays, we're doing these kinds of tests on computers. So you can actually get, you know, probe cognition and cognitive function quite accurately and specifically, by recording people's reaction times and their responses on screens, and we're even using iPads now as well.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: So we're getting a much more sort of fine-grained measurement of people's cognitive abilities. And then actually mapping the brain function changes onto that actually gives another kind of level of depth to what's going on because you can see the neural activity that's underpinning the cognitive responses. And being able to record both of those things down to that millisecond accuracy scale is quite powerful. So you can measure changes quite well now and quite accurately. In terms of clinical improvement, I think that's really down to, you know, what disorder it is you're actually looking at and the kind of treatment you're looking at, and then what you would say is the most relevant or important difference, or what we call the clinically meaningful difference that you're trying to detect in patients.

Andrew: We're going to be talking about dementia and cognitive impairment today. I guess before we go on to that though, do you think with regards to the advances of technology, you know, you're mentioning iPads before, and the way that we interact with that, has medicine caught up with the way that they're assessing cognitive impairment, or are we still using these old you know, gold standards, which are decades old?

Genevieve: Yeah, that's a really good question. And the answer is yes and no. So, no, no, no, yeah, yeah, yeah. Research is always going to be I think, a few steps ahead of what we're doing in clinical practice.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: It does take quite a while for things to catch up and to really have, you know, an effect to change the medical paradigm of what we're doing. And a really good example of that is diet, for example, you know, research has been showing for a long, long time that, you know, eating things like healthy fats, etc., are really quite good for our health and our brain and our heart. But you would have seen, I think it was last week now, the Australian Dietary Guidelines has only just changed to incorporate that…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …and say, it's fine, you can eat full-fat dairy. So is that a good example for you of how the medical paradigm is quite, you know, a few steps behind the research paradigm, and it's really no different when it comes to dementia as well.

One of the issues that we have in dementia is that, you know, it's a very complex syndrome. It's not a, one disease in itself, it's actually a syndrome that comprises more than 100 different diseases. So, diagnosing dementia, or various sorts of dementia can be quite tricky because you don't just have a blood test that you can do like you would with diabetes, for example. You've got to do quite a comprehensive battery of tests that would essentially exclude other causes of cognitive dysfunction and brain dysfunction that might be contributing to the problems that you see in the patient. So, accessing the technology required and the resources required to do those kinds of tests is very difficult. It's also very expensive, and we don't have a lot of access to those things in Australia from a patient care point of view.

So if we talk about Alzheimer's say, one of our kind of hallmarks that you would use to diagnose Alzheimer's diseases is that build up the amyloid protein, amyloid pathology in the brain. And I guess our gold standard way of measuring that in a research setting is to give someone an amyloid PET scan or do a lumbar puncture to say, "Well, we've got amyloid present in the Cerebrospinal fluid." But if you were, you know, John Smith on the street in his mid-70s living in, say, you know, Western Sydney, the likelihood of you being able to access those types of biomarkers…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …is just, second, look, it's minimal, you know.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: We just don't do it because it's expensive. So, yes, technology is moving at a rapid pace, research is moving at a rapid pace, but, you know, we're so far behind in terms of what we're doing from the medical point of view and from a patient care perspective and in terms of diagnosing and evaluating treatments, you know, from a patient care perspective.

Andrew: So with regards to diagnosis in the everyday clinic, how's that made with regards to dementia and indeed, Alzheimer's?

Genevieve: Good question. And it really varies depending on the resources that are available. So you might be, say someone living in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, and forgive me for being so Sydney-centric in our discussion. It's the best parallel I can give you right now.

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: So you might be living in say the eastern suburbs of Sydney, and you would be seeing a, you know, a bariatrician or a neurologist or an old age psychiatrist there. And you may be able to go in and say, "Well, that's no problem. We'll give you these certain tests of cognitive functions." So they might do some pen and paper tests with you. And then they might send you for an MRI and say, "Well, you've got some changes in the volume of your brain." And then, you know, if you're lucky, you might even go and get a PET scan as well to say, "Well, your brain’s not actually performing at fantastic metabolic efficiency, so you've probably got Alzheimer's disease." And you know, that compared to that patient who lives in Campbelltown, where they don't even have an MRI scanner, you know, they'll be lucky to get some pen and paper tests. They might get a CT scan, which, you know, really doesn't show a lot, and that's probably about it.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So it varies very, very widely depending on where you are. But it typically takes, you know, a good few months for a patient to get diagnosed with some degree of accuracy in Australia. The dementia Australia statistics say that it actually takes up to five years for a diagnosis, and that includes the time that it takes for the families to get people who are experiencing memory and thinking changes into a doctor as well.

Andrew: Yeah. And when you're talking about, you know, dementia incorporating over 100 diseases, and then you're talking about diagnosing that with, you know, dare I be so recalcitrant to saying pen and paper diagnosis and clinical diagnosis, and not having any definitive differentiation, then it could very well be coded as the wrong diagnosis, i.e, when you go into hospital, each disease has a code. And if you're given the wrong code, then that's the statistics, the accepted statistics for the prevalence of that disease.

Genevieve: That's correct. So I think that there's two points to kind of pull out there, Andrew. One is around the correct way of diagnosing it. And I think that, you know, from a patient care perspective, if you're not diagnosing it correctly, it means you may not access the correct treatments for it…

Andrew: Yeah, yeah.

Genevieve: …which is obviously a danger. It does happen. We do see a lot of cases, you know, of misdiagnosis or incorrect diagnosis. And a lot of that comes down to what technologies are available at the time the diagnosis is made, the clinician's experience and also their comfort with making a diagnosis. And the type of clinician that does it because, you know, we've done some work with GPs, for instance, who are, you know, obviously, the patient's first point at which they access the health care system on their dementia journey you could say. And GPs often don't feel very confident with diagnosing dementia, even though some of them do make the diagnosis. And sometimes they do it incorrectly. So they may say, "Oh, you've got vascular dementia or Alzheimer's," or just don't even give them a type of dementia, you know. So that's one aspect of the picture.

The other aspect is around the coding that you mentioned. And in Australia, we code for dementia itself. So, you know, in terms of like the AIHW, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare statistics…

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: …and the reports that come out, we tend to just talk about dementia, you know, as a syndrome…

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: …rather than differentiating, delineating, you know, Alzermeirs, vascular, etc. So, in terms of reporting, it's not such a big problem here at the moment, although it would be nice to be able to see the different Australian-based prevalences of the various types of dementia because we don't really do that particularly well here.

Andrew: Got you.

Genevieve: That may...it may improve in the future. There was a big grant that came out of the federal government, I think it was announced last year now, for an initiative called ADNeT. So it's the Australian Dementia Network, which is linking together all of the memory clinics across Australia, and what that will help to do is provide a dementia registry. So we'll be able to be coding people for their diagnosis through a memory clinic network that will be national. So we should see some, hopefully, some interesting new statistics and outcomes on that within the next, you know, a couple of years or five years, I'd say.

Andrew: Now, I know, you know, we've just said over 100 diseases with dementia, so I'm going to pick out one and that is the poster child on, the unfortunate poster child of dementia, and that's Alzheimer's disease. You know, I gather there's certain variants with this as well, but the overarching aetiology that seems to be still accepted, although, am I right that it's questioned? Is that the amyloid plaque and the neurofibrillary tangles?

Genevieve: Yes, that's correct. Yeah. But...

Andrew: Okay. So is this been questioned?

Genevieve: Definitely.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: Yeah, 100%. But, you know, I think it's becoming more and more common and more and more well accepted by the majority of the community researching Alzheimer's disease that we are looking at something that goes well beyond amyloid. And the thought now is that amyloid is probably an innocent bystander in the pathophysiological cascade as opposed to being the primary cause of what's going on.

Andrew: Right. An innocent bystander or a marker? Like, a marker that something else is going on?

Genevieve: Yeah. It's a marker that the disease is there definitely…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …but in terms of its role in the cascade, in causing the neurodegeneration, and, in the beginning of that cascade, it really is, that's really, it's a hot debate at the moment.

Andrew: Yeah. So in my mind, it's kind of like blaming calcium for atherosclerotic plaques, you know?

Genevieve: In a way, yes.

Andrew: Yeah. It seems to be like, well, calcium is actually trying to protect you there. But it's just trying to wall off an insult, but it could well crack and you've got a problem. Is calcium the problem? No. The problem is that you had a plaque there that was growing because of some inflammatory process.

Genevieve: Precisely. It's an excellent analog. Exactly.

Andrew: Okay. So let's go on to that, inflammation. I mean, it's the "cause" of everything. But why dementia? Why...what's happening in these people's brains that causes dementia in them and, you know, not dementia in somebody else that may still have inflammation, you know? What are they thinking? What are the theories around the triggers, the antecedents?

Genevieve: It's really interesting, and from, you know, the perspective of dementia and Alzheimer's disease, specifically, our poster child, as you called it, and also vascular dementia...

Andrew: Ah, yes.

Genevieve: ...yeah, which is our second most common cause of dementia, inflammation is really having a key role around the pathogenesis and then the cascade, so what actually drives the neurodegeneration? And we're really starting to think that this pro-inflammatory environment in the brain is what's driving the neurodegeneration marker and causing these long-term changes.

Andrew: Right. No, I understand the prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's is exploding and that we've got a real healthcare crisis on our hands.

Genevieve: That's right.

Andrew: But is it concordant with the atherosclerotic issues that we're seeing in, you know, our burgeoning waistlines and our diabesity? Is it concordant with that or there's something else going on?

Genevieve: It is concordant with that and there is something else going on as well. So I think it's both things.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: One is concordant in that there are so many common risk factors…

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: …for inflammatory diseases in general, and also a bit specifically around cardiovascular disease and dementia. There's just such a wide array of common risk factors and I'll talk about those in a bit more detail. The other aspect that's kind of, it is and it isn't unique, but it's something that we need to sort of think about with a bit more thought, and that's around advancing age, because age we know is our biggest risk factor for dementia. And as we get older, which we're doing and in an ageing population in Australia, and more and more of us are at risk of developing dementia.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So yes, cardiovascular risk disease also increases with age but I think you'll say that dementia is really being driven by the fact that we're living longer and maybe not so healthfully, and so well as we get older.

Andrew: And we're living with chronic disease. Okay.

Genevieve: Exactly.

Andrew: So here's a statistical projection. If there was a study saying, and I think it was probably around about five years ago now, saying that this generation is going to be the generation that lives the longest and the subsequent generations will not live as long. Does that mean therefore that the prevalence of dementia might actually decrease because they're going to be living less, or is the problem going to be that they're living with chronic diseases for a longer period of time?

Genevieve: Yeah, I think it's that the incidence will eventually decline…

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: …so that's the number of new cases being diagnosed. But once we've got this big, fat group of older people, fat being they measured two ways, fat being that there's a lot of older people and also the waistlines are increasing.

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: As they're moving into their 60s and 70s and beyond in some cases, then we're seeing that the prevalence is remaining high. So whilst there might be a decline in the, so the prevalence is the number of people in the population who have the disease and the incidence is the number of new cases being diagnosed.

Andrew: Got you.

Genevieve: So incidence, I think will see drive down, you know, in the future, but prevalence is going to remain high. We're still going to see that large number of people going through with dementia because of our ageing population…

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: …the baby boomers getting into their 60s, 70s, 80s.

Andrew: Where is the field at the moment with regards to finding a cure for dementia? And is that, indeed, just too big of an ask?

Genevieve: Well, no, I don't think it's too big an ask because I don't believe it's time to lose hope just yet. I think that we're still working on a viable treatment option, and I think that we, or options, I should say, I think there's multiple mechanisms that we can explore that we can target for disease.

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: But if you look at the recent history, you know, there's been 146 failed attempts of Alzheimer's disease drugs over the last 20 years.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: It’s a lot, right? And so I think we need to learn from our mistakes. You know, there's several key factors that really underpin these failures. One is that we're aiming too late in the disease progression. So, by the time someone's diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, you know, we know that there's 10 to 20 years-plus in some cases of pathology that's built up in the brain.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So you're really looking at saying, "Oh, let's try and treat the symptoms of a disease." But, you know, it's kind of, it's gone, it's too late, you've missed the window of opportunity, too little too late. Another factor is around the fact that these treatments that have been used, they really only target one single therapeutic target or mechanism of disease. So, you know, the obvious one at the moment is looking at our, you know, NMDA receptor antagonists or our acetylcholine esterase inhibitors, which is the two primary Alzheimer's disease treatments that are available on the market. And they address one...each of them addresses one aspect of pathophysiology. Where we know that it's such a complex disease with multiple mechanisms, you know, we're talking about, obviously amyloid and tau, but we're also talking about oxidative stress, we're talking about inflammation. And just looking at one single aspect of the disease not going to help with that. And the third part is that we're really only looking at things or in the past, these values, is that we're just looking at trading the symptoms…

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: …around the pathology. So acetylcholineesterase might improve cognition in the short-term, but there's nothing around the mechanism that's actually going to stop disease progression or delay it.

Andrew: Got you.

Genevieve: Yeah. Or we're looking at things like amyloid that may be indirectly involved. So, you know, we're just not hitting the mark, if you know what I mean, the right target.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: So I think there's, you can look at the failures and go "Yeah, we've really failed and there's been a lot of lost dollars around investment. A lot of people's hope has been sort of shattered around finding a cure.” But I think, you know, we're starting to learn that you need to be looking in a different direction, that's around addressing this more complex pathophysiology. It's around looking earlier in disease progression. And it's also around targeting people in their 30s and 40s and doing risk reduction and live, improving dementia literacy so that we're reducing risk earlier on.

Andrew: Dementia literacy. Can you explain that term for us, please?

Genevieve: Yeah. So, you know, some of the things that we find with dementia, is people tend to think it's a normal part of ageing, which it really isn't. It's beyond, well beyond the normal part of ageing.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So it's about understanding the causes of dementia and how much of your risk for dementia is actually modifiable. And it's a huge component. We're looking at well over a third percent of risk is modifiable in Australia.

Andrew: Whoa.

Genevieve: Yeah, it's massive. So, you know, you've obviously got genetics and age, which is non-modifiable, but across the lifespan, you've got up to 35% risk that's modifiable. And in Australia, because we are obese, we are unhealthy, we do have high, you know, cardiovascular disease risk factors, etc., which put us at a high risk of dementia, there's some statistics that suggest that our, what we call our population attributable risk, which is modifiable risk, might be as close as 50%, which is staggering to think that if you can...you've got, you know, almost a 50-50 chance that you can reduce your risk of dementia.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: Yeah. So I think, you know, improving our understanding of that from an earlier age, because it is an across the lifespan approach that we do need to take for dementia risk reduction, that can really help drive down to the future prevalence.

Andrew: Every now and again, you'll see a paper coming out saying, you know, they've found an early target or an early marker of dementia. How's this going? What's happening in this field? Is it, you know, done and dusted where we know what to identify and we can do this now as a, dare I say the word screening or, you know, early detection or are we just sort of?

Genevieve: Oh, goodness no.

Andrew: No.

Genevieve: No. We're far of this. Yeah.

Andrew: Okay. All right. Where we are at? What's happening?

Genevieve: Yeah. One of the issues with this is, you know, I mean, I sort of touched on this previously briefly, and that's around the pathology building up…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …20 years-plus in the brain before there's any clinical signs. And, you know, so if you're starting to say, "Oh, look, this person's got a problem with their memory," and looking for the clinical presentation, it really is too late, almost by that point. So you need to be going much earlier before there's any form of clinical manifestation and deterioration in someone's memory and thinking. So that means that you've got to look at things like blood biomarkers, at brain biomarkers, things from maybe from the CSF, the cerebrospinal fluid or from, you know, urine, faeces, etc.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: So, that's kind of where we're focusing from the biomarker perspective. A lot of the work's been done around amyloid, unfortunately, today, which again, you know, we've talked about the issues with that.

Andrew: Done.

Genevieve: Yeah. They're our innocent bystanders. So now we're leaning more towards looking at things that are related to the inflammation pathway for instance. So not just detecting things like pro-inflammatory cytokines, which we know are elevated in people with Alzheimer's disease, so things like interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 beta and TNF-alpha, but we're also looking at things like tryptophan metabolism.

Andrew: Ah.

Genevieve: So understanding how, you know, the switch from processing tryptophan and it being metabolised into things like you know, serotonin and melatonin and how that's being drived into a different pathway, that that might lead to inflammation. So we can look at a bit earlier on in the disease progression and trajectory to try and understand other ways. And now, that's just one approach. There's many, many, many different, you know, minds approaching this from different angles, trying to look for early markers. Changes in brain structure and function is another thing sort of something that we're looking at as well to see if there's ways that the white matter tracks in the brain, both the structure and the function, are being affected earlier on, and if that's something that we can look at. Even tau, which we know, you know is more closely, so the tau protein is more closely correlated with cognitive decline than amyloid, looking at tau hyperphosphorylation, can never say that word properly...

Andrew: No, it's okay.

Genevieve: ...is, and how tau is spreading through the brain, we think that's starting as early as in our 20s and 30s, possibly, and looking at maybe markers for that in the brain and how that's projected through from the locus coeruleus in the brain stem all the way up to the cortex. And how that might be, you know, a feature marker for disease progression later on.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So there's lots of different approaches. Not we don't have anything solid yet, but we're still I think we're moving in the right direction and looking at things beyond amyloid which is most important.

Andrew: Right. Little, just a little question on tau. I have in my mind the prions of, you know, variant CJD crucible the arc of disease, mad cow disease, the colloquialism. Is tau related to a prion on in the way that it works or acts, or? And the second part of that question is there any way amongst the hodgepodge of biochemistry that we might be able to look at the secretion of tau in urine?

Genevieve: From urine, yeah. I don't think we're as far as urine yet. So yes, in terms of both amyloid and in terms of tau, in terms of it being, I guess, related to things like Creutzfeldt-Jakob, because we're looking at, it really is prion-like an activity that we're seeing…

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: …inactive protein. So it's the misfolding of those proteins and things that go wrong and then they build up, you know, inside the brain. So I think I mentioned before that looking at cerebrospinal fluid, that's kind of one of our, you know, I guess, ways of looking at what's going on in the brain…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …because you know, obviously crosses the blood-brain barrier, which is it gives us kind of a bit of measurement of what's going on in there.

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: That’s one way of looking at it without carving into people's brains directly. And things like the blood as well. But the issue with the blood and things like the urine is because you're looking at something that's circulating in the body or something that's being, you know, metabolised and going through the urinary tract, it's not necessarily going to be crossing the blood-brain barrier...

Andrew: No, that's right.

Genevieve: …you know, and giving the best picture about what's going on there. So, I think, you know, you can look for more downstream markers in the blood and in the urine, and that's probably a better approach than looking directly for the protein...

Andrew: Yeah. Yes.

Genevieve: ...in the cells, yeah.

Andrew: Yeah, but even then, you've got the hodgepodge of biochemistry going on in the whole body…

Genevieve: Precisely.

Andrew: …and you're looking at the urine to track what's going on in one organ, which has got a casing around it called the blood-brain barrier. What about, what about radio labelling things to check tau so with neuroimaging?

Genevieve: Yeah.

Andrew: You know, obviously, you've got to get the medicine in. And if you're not going to do a spinal tap, you know, then you've got to look at something that crosses into the blood-brain barrier. Is that possible? Is that any area?

Genevieve: Yeah. Definitely. So one of the things I mentioned, yeah, at the beginning around our brain scanning is amyloid PET, and we do tau PET as well just not so much in Australia. It's, a lot of it's done in the U.S...

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: ...trials and cohort studies that are done there. But we can, we've got radioactive ligands that we can tag for amyloid and for tau and image those things. There's also FDG-PET, which is you know, looking at glucose metabolism in the brain. And the other one that's kind of just starting to hit off is looking at there's a ligand, I believe the guys at AMSTER are working on this to look at inflammation. So there's a few options there. But the amyloid and tau PET scanning has been around for some time now.

Andrew: And one of the other questions I had with regards to tracking a possible causative factor would be longitudinal studies, because you've got to be able to track dementia over years, right?

Genevieve: That's right. You know, but there are quite a few longitudinal studies and cohorts across the world looking at people and looking at, there's some excellent resources building up like in the UK, for instance, with the Biobank…

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: …they’re looking at people, you know, through their 40s, 50s, and so on. And then, you know, by the time we get to 10, 20 years' time, we're going to have multiple waves of data from these people, that's going to be really helpful with all the imaging and blood markers we get from them. There's other cohorts like the DIAN cohort, which is looking at people who have the APP mutation for Alzheimer's disease. So this is the familial part of Alzheimer's disease, which is relatively uncommon compared to what we see with what we call late sporadic Alzheimer's disease, which is, occurs in 99% of cases. Familial Alzheimer's disease, which is sort of 1% to 2% of cases is when people have this genetic mutation that basically causes them to develop Alzheimer's quite early on actually, 30s, 40s, 50s rather than what we see, you know, typically, which is over the age of 65 and 70.

Andrew: Yeah. Yeah.

Genevieve: So we do follow those people quite closely because that gives us a good...we know they're going to get it, so this is a more cost-effective in a way of measuring longitudinal chains in people…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …and we've got quite a lot of data on them. But, again, you know, there's questions around the similarity in terms of the pathogenesis of the people who carry this genetic mutation and people who have late-onset sporadic Alzheimer's. And to give you an idea, you know, our mouse model, one of our common mouse models, I should say, that's used for testing Alzheimer's drugs is the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model. And that model has been basically formed based on this familial Alzheimer's disease. And so there's some people in the community are saying, "Well, one of the reasons our drug trials have failed is that we're looking at treating late-onset sporadic Alzheimer's with this...

Andrew: With early on-set.

Genevieve: ...yeah, with a different, you know, with the familial type.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: So it may be that there's a disconnect there between the pre-clinical work that's been done around drug discovery and what that, what we're actually trying to treat in, in real-world patients.

Andrew: Right, because I was going to ask you about, you know, with the APP mutation, what evidence is there that we can actually stave off the beginning of dementia symptoms or Alzheimer's symptoms in these patients?

Genevieve: Well, there is some work that's been done in trials around base inhibitors and things like that, but I think, you know, it's one of those things where it's all targeting amyloid.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: You know, and amyloid generation, I just still feel like we're just hitting the wrong targets…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …and we need to be looking at other things.

Andrew: With regards to herbal medicine, you're like when you're talking about radiolabeling, you know, certain drugs for instance, or markers, so that you can neuroimage them. But what about radiolabeling a herbal medicine? Is that the way that the RMIT guys did their work on bacopa?

Genevieve: So the Swinburne guys...

Andrew: Swinburne, sorry. I said RMIT. Forgive me.

Genevieve: No, no, that's okay. So no, it's not quite what they did, because they are looking at the neuronal function which is measured...

Andrew: Got you.

Genevieve: ...yeah, using, looking at the electrical activity of the brain. So you're measuring this what we call the summation of all of these postsynaptic potentials. So it gives you an idea about synaptic function, but it won't tell you about the different, say, you know, concentrations of herbal metabolites in the brain.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So it gives you different aspects of it. But, you know, there's work that we're doing at the moment, for instance, at Western Sydney University that, where we're testing things like, you know, traditional Chinese herbal medicine…

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: …and is also in our trial that we're going to be starting soon looking at medicinal cannabis. And what we intend to do in that study and in the ones that we're currently doing is, yes, we measure all of our classic clinical outcomes for the trial, which are important in showing intervention efficacy, you know, do they improve memory and thinking? Yes. And then we also measure the brain function like what our Swinburne guys have done. So is it actually changing synaptic function? And then what we'll do is run some pharmacokinetics analyses.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So looking at the plasma concentration of different metabolites of these herbal medicines in the blood, and we can correlate that with the changes we're seeing in the brain function and the changes we're seeing in the clinical outcomes with memory and thinking. And that gives us quite a powerful way of saying that any changes that we're seeing are due to the intervention that's being delivered, rather than to some other cause.

Andrew: You are talking about cannabis potentially helping cognition. The stereotype would be that cannabis dulls the senses, you know, is somniferous, that sort of thing. You're talking about helping cognition and helping people to think by using cannabis products.

Genevieve: That's correct, yes. It's very counterintuitive, isn't it?

Andrew: Absolutely.

Genevieve: Yeah. And I think one of those things comes down to, you know, A, some very well ingrained stereotypes about cannabis.

Andrew: Yes.

Genevieve: Obviously, you know, THC is the bad brother, you know, and CBD is the good brother and if you have too much THC, it means that you're going to be impaired. And look, there is there obviously are some elements of truth to that because if you're taking THC, you are going to have some psychoactive effects that will cloud memory and thinking. But, you know, it's about looking at beyond just the psychoactive effects because there's lots of therapeutic properties of other cannabinoids.

Andrew: Yes.

Genevieve: And when you combine multiple cannabinoids together the synergistic effects that you get between them can help to improve cognition. In, we know in mice, it can, so in our transgenic mouse model. And we also know that in humans who have chronic cannabis use and already have impaired cognition, when we give people like that kind of cannabidiol, so CBD…

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: …then we see an improvement in their cognition.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So it's quite interesting actually because it's counterintuitive, isn't it? You think that if you have cannabis, you're going to get worse.

Andrew: I thought I knew about cannabis and a very quick discussion with Justin Sinclair revealed that I did not.

Genevieve: Justin is a major, he's a wealth of knowledge in this area.

Andrew: But, you know, I know and I wasn't against it. I was favourable to it but I didn't know about it. Now you were, you were just alluding to something that's really interesting to me there. You're saying people with long chronic cannabis use who had dulled senses, and they increased CBD, not THC, and that increased their alertness. It couldn't be, therefore, that the problem with our stereotypical view of cannabis was that we're using the wrong sort of cannabis from the illicit drug trade?

Genevieve: Potentially, potentially.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: But I think what was interesting about that study is that they actually did a subgroup analysis, and they looked at people who are high and low users of cannabis.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: And what they showed is that when they gave them CBD over 10 weeks, it was actually the people in the high usage group that had the improved cognition. And there's two arguments around that I think, that are interesting. One is that they had a bigger kind of room for improvement because they could have had more severe deficits to begin with because they're, you know, smoking more straight weed or whatever.

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: But the second argument, which I think probably is the most compelling one, is that these guys are actually consuming, yes, your straight sort of based cannabis, which typically has a higher THC content because, you know, people consume it.

Andrew: Want to get high.

Genevieve: Yeah, exactly, they want to get high. So you're looking at something, they're already having more THC. And then when you give them CBD on top of that there's something that goes on when you combine the two together that gives you a better bang for your buck in terms of therapeutic value.

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: So, and that's the bit that I think is the most interesting. So they're not 100% sure if that's what drove the results, but we're sort of leaning towards that might be what's happened. And that's kind of something that we're thinking about replicating in now in our future study looking at people who have early-stage Alzheimer's disease.

Andrew: And what about the entourage effect? You know, the terpenes, the flavonoids that sort of thing?

Genevieve: Yeah, yeah. So there's lots of evidence there, around the therapeutic efficacy of different cannabinoids. So, you know, for instance, that, you know, terpenes they've been, you know, implicated in Alzheimer's pathology and also in symptoms. You've got, you know, things like symptoms of Alzheimer's like depression, we think that things like limonene might be useful for that with the aggressive symptoms you see later on things, like linalool. You know, so there's a range, even amyloid plaque formation those things implicating things like THCA. So a range of different cannabinoids...

Andrew: Right.

Genevieve: ...implicated in various aspects of pathophysiology, but also in terms of the clinical outcomes as well. Another one that comes to mind is the Alpha-pinene…

Andrew: Yep.

Genevieve: …and how that's related to memory as well.

Andrew: Got you.

Genevieve: So I think, you know, looking at, if you're just taking this narrow approach and saying, "Well we've got this amazing plant that's got all these different, potentially therapeutic components," and then just taking one of them and even making it synthetic or just giving people a high dose of that only, we might be missing the picture. And in, you know, we've talked about what's gone wrong in the trials that have failed for Alzheimer's disease drugs, I think we've got to avoid going down that path again with...

Andrew: Yeah, don’t do it again.

Genevieve: Exactly. Just take one thing because we know what this mechanism is and see how it works.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: Actually, that's a bit of a reductionist approach and I think we might be missing the bigger picture.

Andrew: Humans aren't good at looking at complex interactions are we?

Genevieve: No. And look, the scientific paradigm is we're just not set up to test that, you know, and even personalised medicine where everybody's built differently, we all metabolise differently, we need different ratios and doses of things, you know, the scientific paradigm around clinical trials is just not designed to test those kinds of effects. And it's a real shame because if you think about how modern medicine works, you know, you, if you go in Australia today to be prescribed cannabis, which is it's challenging at best, but save for chronic pain and go and visit a GP who's a registered prescriber, they're not just going to give you a standard formulation, they're going to try out a few different things, different ratios, they're going to titrate the dose, you know, they're going to just find the sweet spot for you what works.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: And, you know, I think thinking about personalised medicine approaches like that, that's probably going to be the wave of the future for cannabis. But hopefully, we're also testing things like, you know, metabolites, and how we're actually, you know, metabolising things and how our body's responding to it at a more biochemical level, and not just going "Well, do you feel better?"

Andrew: Yeah, that's right. So tell us a little bit more about the trials that you're running for mild cognitive impairment and dementia.

Genevieve: So we've got one trial almost finished now, actually. So this one was NHMRC-funded. And it's looking at Sailuotong or SLT, which is a traditional Chinese medicine formula that's been specifically developed for vascular dementia. And what I love about SLT is it’s, I call it a drug because it's not the sort of what you would think of if you go, "Oh, TCM, like a traditional Chinese herbal medicine. I've got, you know, I'm going to go and see a Chinese herbal medicine practitioner and get a mix of herbs, and I'll go and make them up and take them." It's been developed like any drug in a western medicine paradigm would have been developed, so through the full drug discovery pathway. So all of its, you know, its chemical composition's been well established, the ratio of the three different herbs, so it contains ginko, ginseng, and saffron. The ratio has been very well defined and tested in pre-clinical studies. We know how, you know, it's toxicology profile's been tested, we know what dose we should be taking. It's all been done over the last 15 years. And it's currently at the point where they're in phase three trials for vascular dementia.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: They are doing studies in China, yeah, and we've got a phase 3 on the way here also at NICM at Western Sydney University, looking at vascular dementia. And so taking that approach that I was talking about before was saying, "Are we looking too late in the disease trajectory?" We thought “let's look a bit earlier in that disease pathway and target people with mild cognitive impairment and see if SLT's going to have an effect on them.” And people with MCI are a really fantastic patient group to look at because they have problems in memory and thinking so they are...MCI is a clinical syndrome you know, you can go to a specialist and be diagnosed with MCI, as tricky as that can be, it’s something you can measure. But people with MCI don't have any impairment in their function and independence, yet they're still able to adopt different strategies to deal with memory impairment.

Andrew: Right, right.

Genevieve: So they're able to comply to treatment really well and they don't necessarily need a carer to kind of help them with things. So they are really engaged group to work with, but they also this sort of what I call the window of opportunity.

Andrew: Yeah.

Genevieve: They're at an early stage where you might be able to do something and actually improve cognition and possibly delay deterioration in the future. So that's one of the studies we're looking at is SLT. And we're about 80% of the way through that one. We're going to finish that one at the end of the year or sort of January 2020 at the latest.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: It will be very exciting.

Andrew: Really excited.

Genevieve: Yeah. Really excited. And I can't tell you the results yet…

Andrew: Nope. Nope.

Genevieve: …because we're not allowed to talk about it until we're finished. So as much as I want to look, I can't. I've been doing some kind of across groups analysis, and it looks like there's some trends towards improvement in what we call episodic memory, which is our ability to be able to remember kind of episodes or events in life, and that's like the hallmark of Alzheimer's disease. But that's across groups. So we don't know if it's a placebo-driven effect, or if it's something that the treatment is actually driving, but it's there.

Andrew: Got you. .

Genevieve: So I'm really excited to see that.

Andrew: I can just see you champing at the bit going "I want to break the code, I want to break the code."

Genevieve: Pretty much, yeah, but no I can't. I don't have the code so I can't break it. That's through someone else. But the temptation is up there.

Andrew: You were mentioning a cannabis trial just before.

Genvieve: Yes, that's right. Yeah.

Andrew: Yeah. Is that...

Genevieve: So that's still, yeah that’s still in development at the moment, but we're really excited about that one as well, which will launch next year sometime. So that's all secret squirrel right now and I can't tell you too much about exactly what we're doing. But we are looking at cannabis for people with MCI. So again, it's in this earlier disease stage. So we're super excited about that. We think you've got great protocol. We've got a fantastic team of international experts that are going to drive this.

Andrew: Wow.

Genevieve: And I'm really, you know, out of all the things I'm looking at, yes, I'm excited about our full team, of course, but I really feel like this might be one of, it could be the winning ticket but we don't know yet. We don't know.

Andrew: Yeah. Like we can only hope. And it's not...

Genevieve: Yeah, exactly.

Andrew: For me, it's not for cannabis, it's for these patients that are suffering and then indeed their families.

Genevieve: Exactly.

Andrew: And their people that they interact with who are suffering, their carers, they're all suffering together. And if we can help them with something, I don't care if it's herbal or whatever, I don't care if it's a drug. I just would love to see this group of patients being helped, because, as you say, 146 failed drug attempts over 40 years.

Genevieve: 20 years. 20 years.

Andrew: Twenty years. It's not a good track record. I can only hope that this shows some sort of succour, some help for these patients who are really suffering.

Genevieve: Yes, yes. Me too, Andrew. And that honestly to tell you, that is the driving point of what we do, you know, where every aspect of the research that we do is about trying to find a way to help these people. And, you know, it's because all of us have been touched by dementia in some way. You know, you think about things like cancer as well, it's so similar. I'm sure you know, and most of the people you work with, it's the same with us, we all know somebody who has dementia, you know, a grandparent, a parent, an aunt, an uncle, you know a friend. There's just so many people out there who are experiencing these difficulties. And whatever we can do to help people, and if there's a way to stop it from happening to begin with, then that, you know, I'm all for that.

Andrew: Doctor Genevieve Steiner, I can't thank you enough for your care for your patients and indeed the care for future generations who suffer from this debilitating...these debilitating illnesses. Thanks so much for joining us on FX Medicine today.

Genevieve: Thanks for having me, Andrew.

Andrew: This is FX Medicine. I'm Andrew Whitfield-Cook.

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.