It is inevitable that there will be some degenerative change in our joints over our life time. Up to 85% of people over 65 show some evidence of osteoarthritis (OA), with about half experiencing symptoms including pain, decreased mobility and decreased functional capacity.

Several key factors appear to contribute to the development of OA. The most apparent of these is simple wear and tear, with intense repetitive activity, overuse or structural imbalances resulting in an increased incidence of joint degeneration. Moderate exercise, however, has been shown to prevent OA of the knees by maintaining muscle strength of the quadriceps.

Genetic factors also seem to play a significant role with researchers estimating that they may affect between 30-60% of people with OA.

The conventional medical approach generally targets the symptoms of pain and inflammation, with the use of medications such as paracetamol, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors being first line considerations. These drugs do little to modify the progress of OA and, along with the risk of serious side effects, long term use may in fact exacerbate degenerative joint conditions.

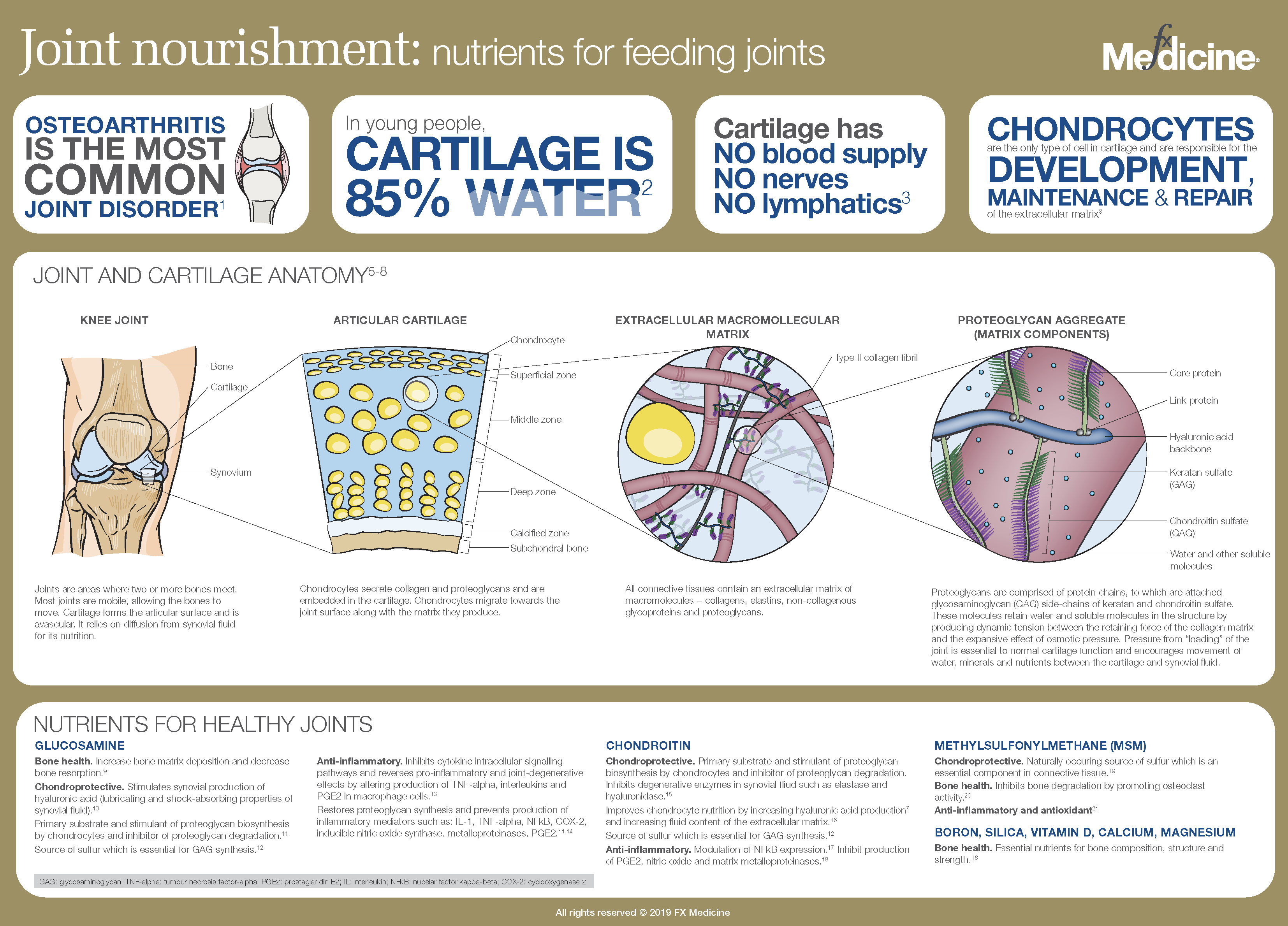

From a natural medicine perspective, there are a number of safe and well studied recommendations that are well worth considering. Recent studies now further support the use of glucosamine, MSM and chondroitin for the treatment and improvement of OA. In addition to this, attention should be given to the full array of cofactors required to maintain healthy joint function including silica, calcium, magnesium, vitamin D and boron.

In this infographic we explore how nutrients contribute to joint nourishment for the improvement of joint structure, pain and function.

References

- Osteoarthritis 2014. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2016. Viewed 5 February 2016, http://www.aihw.gov.au/osteoarthritis/

- Mishra C. Understanding osteoarthritis and its management - (for physiotherapists). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishing 2012. [Source]

- Fox AJS, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage. Sports Health 2009;1(6):461-468. [PDF]

- Kumar P, Clark ML. Clinical medicine, 8th Ed. London: Elsevier 2012. [Source]

- Mescher AL. Junqueira’s basic histology: text and atlas, 14th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015. [Source]

- Pollard TCB, Gwilym SE, Carr AJ. The assessment of early osteoarthritis. Bone & Joint J 2008;90-B(4):411-421. [Full text]

- Heinegard D, Saxne T. The role of the cartilage matrix in osteoarthritis. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:50-56. [Abstract]

- Izadifar Z, Chen X, Kulyk W. Strategic design and fabrication of engineered scaffolds for articular cartilage repair. J Funct Biomater 2012;3(4):799-838. [Full text]

- Nagaoka I, Igarashi M, Nakamoto K. Biological activities of glucosamine and its related substances. In: Se-Kwon K (Ed). Advances in food and nutrition research (pp 337-352). Tokyo: Academic Press, 2012. [Full text]

- McCarty MF, Russell Al, Seed MP. Sulfated glycosaminoglycans and glucosamine may synergies in promoting synovial hyaluronic acid synthesis. Med Hypotheses 2o00;54(5):798-802. [Abstract]

- Roman-Blas J, Castaneda S, Largo R, et al. Glucosamine sulfate for knee osteoarthritis: science and evidence-based use. Therapy 2010;7(6):591-604. [Abstract]

- Nimni ME, Cordoba F. Chondroitin sulfate and sulfur containing chondroprotective agents: is there a basis for their pharmacological action? Curr Rheum Rev 2006;2(2):137-149. [Abstract]

- Kim MM, Mendis E, Rajapakse N, et al. Glucosamine sulfate promotes osteoblastic differentiation of MG-63 cells via anti-inflammatory effect. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2007;17(7):1938-1942. [Abstract]

- Hua J, Sakamoto K, Nagaota I. Inhibitory actions of glucosamine, a therapeutic agent for osteoarthritis, on the function of neutrophils. J Leukocyte Biol 2002;71(4):632-340. [Full text]

- Raoudi M, Boumediene K, Roche R, et al. P152 effect of chondroitin sulfate on hyaluronan synthesis in synoviocytes and articular chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:S79-S80. [PDF]

- Braun L, Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence-based guide, 4th ed. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2015. [Source]

- Martel-Pelletier J, Kwan Tat S, Pelletier JP. Effects of chondroitin sulphate in the pathophysiology of the osteoarthritic joint: a narrative review, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:S7-S11. [Full text]

- Pecchi E, Priam S, Mladenovic Z, et al. A potential role of chondroitin sulphate on bone in osteoarthritis: inhibition of prostaglandin E(2) and matrix metlloproteinases synthesis in interleukin-1beta-stimulated osteoblasts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012;20(2):127-135. [Full text]

- Kim LS, Axelrod LJ, Howard O, et al. Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: a pilot clinical trial. Osteoarthritis & Cartilage 2006;14(3):286-294. [Full text]

- Joung YH, Lim EJ, Darvin P, et al. MSM enhances GH signaling via the Jak2/ STAT5b pathway in osteoblast-like cells and osteoblast differentiation through the activation of STAT5b in MSCs. PLoS One 2012, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047477 [Full text]

- Methylsulfonylmethane. Alt Med Rev 2003;8(4):438-441.

This image by FX Medicine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

More information about how to share/use the infographics for personal use.

If you interested in using any FX Medicine content for commercial use please contact us.

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.