In part one of our two part podcast, Dr. Andrea Huddleston, naturopath and chiropractor and expert in women’s health and reproductive medicine, speaks with our ambassador Dr. Damian Kristoff about women’s health and reproductive dysfunction.

Andrea shares two of her top five causative factors associated with hormonal dysfunction starting with stress and spinal position, both of which are strongly associated with hormonal imbalance and uterine positioning. Andrea and Damian discuss the prevalence of stress and ways it influences hormonal levels and the role the autonomic nervous system plays on uterine function. The position of the spine and the connection it has on uterine positioning and function is discussed as we learn about the signs and symptoms associated with an anteverted and retroverted uterus.

Covered in this episode

[00:39] Welcoming Dr. Andrea Huddleston

[01:28] Why we are seeing record levels of hormone dysregulation and how stress plays a role

[06:52] Managing the autonomic nervous system

[09:57] How the spine, posture and pelvic position affects menstruation

[15:22] Clinical symptoms to help differentiate between an anteverted or retroverted uterus

[24:22] Why the uterus is important for proper ovarian function

[27:30] Connections between body weight and dysmenorrhea

[30:57] Injuries to the coccyx

[35:50] Hormones are directly associated with pain levels

[41:47] Thanking Andrea and closing remarks

Key takeaways

- A woman’s menstrual cycle can provide insight into the health of the woman.

- The uterus is under autonomic control, making positive changes to the nervous system important to support uterine and ovarian function.

- Chronic levels of reproductive dysfunction are attributable to poor diet and lifestyle including high stress levels impacting our hormone levels and reproductive health.

- Increased stress results in progesterone being diverted to produce high cortisol levels taking up the progesterone required for optimal oestrogen-progesterone balance, impacting the menstrual cycle.

- The position of the spine and pelvis influences uterine positioning and in turn, menstrual health.

- Anteverted uterine positioning may require increased myometrial contracted to expel menstrual fluid against gravity, leading to increased menstrual pain before the onset of menstruation each month. The anteverted uterus may also increase dragging pain in the legs, vagina and lower back and may present with increased urination leading up to menstruation .

- A retroverted uterus is often associated with infectious scarring from pelvic inflammatory disease and sexually transmitted infections or endometriosis adhesions. Signs of a retroverted uterus include low back or sciatica pain upon menstruation, ovulation pain, constipation or thin stools prior to menstruation as the uterus places pressure on the rectum.

- Injury to the sacrum or nerve damage to the sacrum may be associated with changes to nervous system function of the uterus and may present with mentrual symptoms such as dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia.

- Body composition can influence uterine positioning, menstrual symptoms such as dysmenorrhea as increased adipose tissue secretes interleukin-6 and oestrogen promoting oxidative stress leading to slower, more painful uterine lining shedding.

- Hormonal regulation can directly influence pain perception. Testosterone may provide pain protection while oestrogen can be both pro and anti-inflammatory. Low testosterone levels in men are associated with increase pain and inflammation.

Resources discussed in this episode

Transcript

Damian: This is FX Medicine, bringing you the latest in evidence-based integrative functional and complementary medicine. I'm Dr. Damian Kristof, a Melbourne-based chiropractor and naturopath and joining us today is Dr. Andrea Huddleston.

She's a women's health natural fertility expert, and integrative chiropractor practicing in Perth. She's the co-host of the award-winning, top-rated podcast, Wellness Women Radio, and is affectionately referred to as the “Period Whisperer” by her patients. In addition to her chiropractic degrees, Dr. Andrea holds two postgraduate master's degrees in women's health medicine and reproductive medicine. She is a leader in women's health, a great friend of mine, a sought after presenter, avid coffee addict, and a crazy dog lady.

Thank you for joining us today, Andrea.

Andrea: Thank you so much, Damian. I'm super happy to be here.

Damian: Great. Hey, Andrea, when we look around, and you and I see a broad range of different patients, and I suppose these days you've really narrowed, I suppose, your...not narrow, but you're very specific. People come to you because of hormone dysregulation. You're known as the Period Whisperer for a reason. Like there's a reason why you're known as the hormone whisperer and the period whisperer. So we're seeing record levels of reproductive dysfunction, more than ever before. What are your thoughts on this? What's the problem? What's going on?

Andrea: That's such a good question. And I think just like any other chronic health condition, I think it's because our current lifestyles just aren't conducive for optimal hormonal function or optimal reproductive function. And I like to think of the menstrual cycle as being, or it should be considered really that thick, vital sign. So just as an important marker of health for women, as it's something like their own blood pressure, because it gives us this clue into the overall health of that woman and the well-being of that woman as well. And this is not just for cycling women in their reproductive years, this is also as we transition into, say, perimenopause and menopause. The longer we cycle for, for example, really dictates the health of women later in life.

And if we want to get really specific about the things that I think are causing so much of this reproductive dysfunction, I sort of oversimplify things into what I think are the main causative factors of hormonal dysfunction, and I call them my “five S's of hormonal imbalances.” And the first part of that, Damian, if you want to sort of get started on that straightaway.

Damian: Yes, let's go in that. Yes. Yes.

Andrea: We can dive into that. So my first S of that is stress, right? And...

Damian: No stress at the moment, is there? No stress anywhere.

Andrea: No. Nothing. It's definitely not over here in Western Australia. We're so stress-free. It's ridiculous.

We're all under unprecedented amounts of stress and pressure at the moment, but this was occurring well before the pandemic hit, even. And I think the amount of pressure on women and the amount that we take on and the lack of balance that we have in our lives and everything else certainly contributes to just the breakdown of our system.

And even if we just look at from, say, like a biochemical level, if we're under that, that chronic stress, we're producing lots and lots of cortisol, then we're robbing progesterone to make more cortisol and then we're getting this unregulated ratios between oestrogen and progesterone, and then our thyroids are shutting down. And I sort of explain to my patients that whole stress hormone cycle so they can really understand that just from the pressure at work or just from constantly rushing around, all of those things can be why their hormones are so all over the place and why we're seeing such statistics of almost every woman with some sort of hormonal dysfunction. It's a pretty sad state of affairs, I think, for women's health at the moment. So stress...

Damian: Would you say that pretty much every woman has some kind of hormone dysfunction? Is that what you're saying? So whether it'd be acne, whether it'd be period pain, whether it'd be endometriosis, whether it'd be PCOS, whether it'd be amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, whatever, shortened cycle, lengthened cycle, pain on menstruation, stress on menstruation, emotions on menstruation. Would you say that pretty much every woman's got some kind of dysregulation?

Andrea: Look, and I think that this subset of the sample of patients that I see probably makes me a little biased in this, but I really do think that that is the case. Because if we look at statistically they say about one in nine women have endometriosis. I think it should be a bit higher than that, but let's just round up and say about 10%. Up to 21% of women have PCOS, and those two conditions rarely overlap. So that's like 30% of the population now.

About one in four women have some sort of fertility challenge. And then I'm sure, Damian, you experience this as well, like I'm seeing thyroid conditions pop up in almost epidemic proportions, especially after women have had their second or third baby. And then, finally, women who experience period pain that is enough to interfere with their activities of daily living or require pain medication is like 95% of women. That's just period pain. So, statistically...

Damian: That's more than every woman.

Andrea: I know. That was a terrible pitch that I was going on.

Damian: Wow.

Andrea: But even just in that first section, that's at least 30% of women who have some sort of diagnosable hormonal interference.

Damian: Yes. It's that as well.

Andrea: And there's certainly reasons for this as well and certainly stress is one of them. But I think this is also the way that women have been treated within the standard Western medical model. And the treatment approach to that, I think, can be part of why we're seeing such dysfunction these days as well.

Damian: We're talking almost organic or we're talking more about biochemistry here. And when we talk about stress, that's an autonomic nervous system function, right? So stress in itself is an autonomic nervous system function. So we know that that's brain derived, the brain is signalling, it's feeding forward, feeding back, it's receiving information, sending information. That comes from the brain and the spinal cord.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: So we're talking about a neurological function but often we're talking about the management of it with biochemistry. And to me, there seems to be a little bit of a disconnect. But where I want to go with that is that for much of what we talk about in terms of the management of these issues, particularly in around stress, and we'll come back to all the other S's shortly.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: But when we look at this, we kind of go, okay, well, then, as a naturopath, I've got my naturopath hat on here. And I think about “How do I manage the autonomic nervous system?” I might throw magnesium at it. I might throw some herbs at it. I might throw maybe some behavioural changes, whether it'd be walking, or meditation, or some other different things.

If I put a medical hat on, I might look at anti-anxiety medication, or sleep medication, or whatever else. So there's these biochemical influences over that. But there's food that is biochemical, there's pharmaceutical and nutraceutical and phytoceutical interventions that we might consider. But we're talking neurology here. We're talking about the nervous system and the brain. So, can we delve into that a little bit? Can we talk a bit more about that?

Andrea: I would love to. And, Damian, you are going to be so much more succinct at explaining this sort of thing than what I am. But I know for my patients, for example, part of the way that we would address the chronic stress would certainly be through all the avenues that you've just discussed. We might use herbs, we might use lifestyle and dietary interventions, and looking at what the root cause of those triggers are, and everything else.

But then the other intervention that we have is obviously adjusting them. And from the way that I experience the changes with that is that they then experience their environment and those stresses differently. And even if we just look at how, because obviously we're talking about women's health and reproductive and hormonal function, the uterus itself is under autonomic control. So, therefore, changes in the nervous system is absolutely going to change how the uterus is functioning, which will then have a flow on effect to how the ovaries are functioning because we need that functional uterus for adequate ovarian function as well.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: I’ve said that word too much now.

Damian: It's a functional medicine podcast you know, FX Medicine.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: So, that's functional.

Andrea: Yes, that's very true.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: But we need that brain-body connection to be working adequately for optimal function.

Damian: Yeah. Well, that's a great point. And so when we think about that in terms of distortion, so we're talking about dysfunctional in, say, an autonomic nervous system sense or dysfunction in terms of dysregulation of the hormones, they're very closely related and easy for us as chiropractors and us who are well versed in both the biochemistry and the neurology overall of that.

It's easy for us to kind of see that, but how do we explain that to our patients? Like how do we explain that? Let's say I'm a naturopath right now or an integrated GP right now, how do I explain that, yes, there is a biochemical component but the brain controls all of that, the brain is your master controller in this sense, so it's under autonomic control. Is there a way in which we can explain that easily?

Andrea: I think the way you just did that, sounded really succinct to me, Damian. That was beautiful.

Damian: There it is.

Andrea: The most simplistic way is the brain that is the control mechanism of everything. And so if we don't have that brain-body connection happening, then what are we going to see that changes after that?

And I know that even if we look at - and maybe we'll get into this shortly - but one of my five S's of hormonal imbalances or of hormonal problems is actually spinal problems. And it was just handy that spine starts with an S, and so I think I could include it in my five S's.

But it really is, for what I see in practice and my interpretation of the issues that we're seeing in women's health that the posture of a woman and the pelvic position and pelvic distortion patterns and everything else dramatically influences, for example, menstrual health. And this is documented. There was research that supports this as well. And it's something that I see in practice every day. Damian, should we dive into a little bit more about that now?

Damian: I'm so glad you said that because that's where I wanted to go. Because I thought, "Oh, great, you brought that up."

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: So let's go into that. So I was going to ask you, is there a link to the health of the pelvis and pelvic distortion? That's the question. And I'd love us to just kind of head to that direction because you've gone to that “S.” Let's head there.

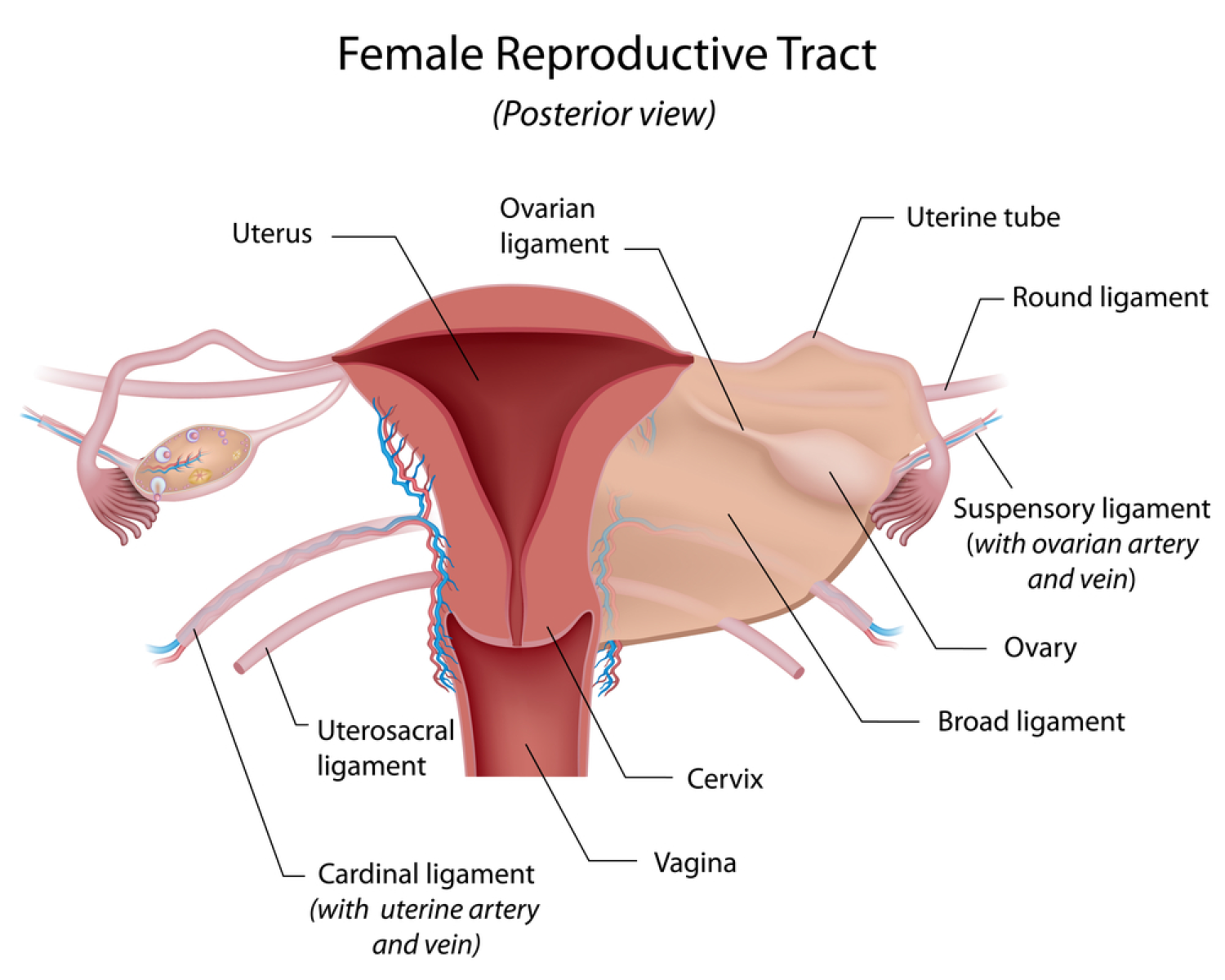

Andrea: This is one of the most fascinating things that I find in women at the moment and I'm a little bit obsessed with it. And that is this idea of pelvic position and how it relates to uterine position. And really simply without going into like super in-depth anatomy, the uterus is not really attached to anything. It's suspended within ligaments that anchor into the pelvic bowl and the most important ones that really maintain that uterine position, and I'll bring it back to why that's relevant shortly, is the uterosacral ligament, which attaches into the front of the sacrum and then to the cervix. And then there's the cardinal ligaments that go from the cervix to the base of the pelvis or the ischium, and then the pubocervical ligaments that go from the cervix to the pubic symphysis. So I'm like moving my hands to try and show you, but I realised this is audio, so that's not helpful at all.

Damian: We might need some pictures. We might need some pictures. We'll get a diagram to everybody. Go to the show notes. Don't forget to go to the show notes to get these diagrams because they're great diagrams. They're awesome.

Andrea: Yeah, totally. I'll send you those for sure. So I want you to understand that the uterus is suspended within those ligamentous structures. And about 75% to 80% of women have an anterior pelvic tilt or that forward pelvic tilt. And I don't think it's a coincidence that that same percentage of the population also have an anteverted uterus. So that's forward tilting uterus. And the reason that this is important is because when women menstruate, part of the movement and the flow of blood with menstruation is simply with gravity. And it's with those uterine contractions that happen to expel the blood. However, if you have more increased flexion of the uterus in either anteversion or retroversion, so backwards tilting, then that blood pools in that front surface of the uterus...

Damian: Oh, wow.

Andrea: ...which means that it requires stronger myometrial contractions to actually expel that blood. And that those myometrial contractions are cramps, they're period cramps, that's the period pain or a big portion of the period pain that women experience during their period.

And it's a biomechanical position or issue of the uterus, when we've got a pelvis that's sitting in that sort of forward, flexed position, and then we've got the uterus, which is also anteverted and it might be anteflexed or anything like that, or if we've also got a retroverted uterus. But it's the degree of flexion in either anteversion or retroversion, which is an independent risk factor for dysmenorrhea or period pain. And it's not associated with pregnancy.

So this is independent of those things that we know that period pain goes up according to that degree of flexion. So that optimal uterine position which is dictated by optimal pelvic position equals better menstrual health, less painful periods. And then we can sort of expand that to possibly better reproductive function as well.

Damian: Wow. This is mind-blowing. I'm a chiropractor, I know this stuff but hearing it is unbelievable. This is so good. And I wish this was live, and we're going out to the millions of listeners that we do have, and I was watching those little light bulbs go off because people will be going, "Oh, my gosh. Oh, my gosh, like this isn't just a simple vitex issue. This could be a positional issue." And this is absolutely fascinating. So you were saying...

Andrea: Yes. And there's hints that like the practitioners can look for as well. Because you may not know if your patient has an anteverted or a retroverted uterus, but this is something that I think should be part of a clinical consideration whenever there is a complaint of, for example, primary dysmenorrhea, or even just any kind of menstrual associated pain that is in the instance of endometriosis as well. I think that this always needs to be looked at or addressed because of the prevalence.

So, Damian, I can talk through some really easy symptom pitches that they may be able to look for to help differentiate, say, an anteverted versus a retroverted uterus, if that would be helpful.

Damian: Yeah, let's do that, because I know everyone's going to want to know, "Like how do I know that it's not just a progesterone issue?" That's what they're going to be asking.

Andrea: Yeah. Yes. Okay.

Damian: I've simplified that. I've made that really basic.

Andrea: Yes. Totally.

Damian: And that's probably not what they would ask me. But it's like I'm going, how do we add an extra layer there? Like what are we looking for to kind of understand where should our clinical thought go? How do we reason with this to decide what's the cause of someone's dysmenorrhea?

Andrea: So I think, obviously, a really thorough history taking around that, and understanding the quality and the timing of the pain as well. So normally, one of the biggest indications that I see with a patient who has like a positional issue that's contributing to her period pain is she will get pain and cramping before the bleeding starts. And because it's almost like the body is trying, trying to expel that blood, but there's that structural component to it where things aren't moving as well. And obviously, we've got to address things like the prostaglandin release and hormonal imbalances and everything else along the way, but this is such a huge part of that.

Damian: Of course. Yes.

Andrea: And with anteverted uterus and, yes, anatomically, the uterus sits slightly anteverted anyway. But as it increases in that anteversion, you might get that classic, anterior pelvic pain. The patient might describe dragging into their legs, they may get pain into the vagina, or the lower back, sometimes during sex as well. They may have trouble inserting tampons, but they might feel like some sort of internal pressure even with proper insertion.

As they're getting or building up to their period, they might notice increased urinary frequency or getting that fullness of their bladder as well. So they'll feel that pressure of obviously the interior structures of the uterus pushing into the bladder. They might have higher rates of things like UTIs. They might get mild incontinence, but also you might actually just see on them that they might have just that little pooch or that protrusion of that lower abdominal area.

Damian: Yes. Which is very common, like it's very common these days.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: If 75% of women have an anteverted pelvis, then that's more common than uncommon.

Andrea: Exactly, yeah. And women will often come in with ultrasound reports that describes the position of the uterus. So that's a little bit of a cheat sheet for us. But if you're pretty skilled, you can also palpate the position of it too. And just with a symptom picture, it's really easy to differentiate what you're dealing with, whether it's an anteflex uterus or retroverted.

And I find that a retroverted uterus is much more of an almost pathological condition. So the reasons why a woman might have a retroverted uterus is often from things like infections, it might be uterine scarring from infections like pelvic inflammatory disease, STIs, it can be obviously from endometriosis adhesions as well. It can be from...

Damian: Yes. One thing we don't talk about in that regard with regards to scarring, could abortions have anything to do with that? Could there be anything else, maybe scraping the uterus to reset or to...there's all these different types of interventions. No one talks about that. Could that be something?

Andrea: Oh, excellent question, Damian. I actually haven't looked into the role of like the D&C, for example...

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: ...and what kind of scarring and whether or not there's adhesion formation from that. I'm not sure. But that's definitely something that I'm going to look into because you have piqued my interest there. But certainly...

Damian: I just wonder, because it's happening more and more. Maybe not more and more, but it's happening.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: And so could that be something that we miss in our clinical diagnosis in our note taking? How many of us are asking what sort of surgeries have you had and do we just gloss over the potential that might actually have something to do with it?

Andrea: And certainly the more like laparoscopic surgeries that a woman might have is certainly going to increase scar and adhesion formation. We know that. And while that is obviously still the gold standard medical treatment option for endometriosis, there's pros and cons there.

Damian: Yes. Totally.

Andrea: Women can also have a retroverted uterus from big falls on their sacrum. And just poor pelvic alignment from chronic high heel wearing, poor posture…

Damian: They look so good though.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: They look so good, high heels. That's the thing that I get when I mention that to ladies, high heels could be involved, could be part of the problem. And they'd like be, "Yeah, but they look so good. I'm not ready to give up high heels yet." So that's often something that I get told.

Andrea: Yeah, and I totally understand. And I'm probably as vain as they come. But you have to really weigh up the, "Can you fence it with this?" And if you have severe period pain, I would expect that you can ditch your high heels for a while, if that's indicated. That's just my take on it anyway. My patients know that they cannot wear heels into my practice, otherwise, they have to leave barefoot. But also I'm a bit of a hypocrite because whenever I'm teaching, for example, and Damian you would have seen this, I'm always in super high heels. But I think that's part of of the outfit. It helps get you in the zone.

And some of the signs and symptoms that practitioners may be able to tease out to determine whether or not this patient may be looking at more of a retroverted or retroflex uterus can...normally I see much stronger period pain with this position. And you'll get normally low back pain during the period rather than just that classic anterior pelvic pain. You can get changes in bowel movements as well during the period. So women might explain things like constipation or really thin stools before the period.

Damian: Okay.

Andrea: And because obviously, the uterus grows so significantly in volume just before menstruation, and it pushes into the back of the rectum. So that's why just their bowel movements can change. And it will be so much heavier if there's something like adenomyosis or sort of fibroids that are present too.

Damian: Yeah. Right.

Andrea: And some women can even experience really foul-smelling menstruation. Because in that position with that heaviness on the rectum, they can actually get sort of toxins from the bowel seeping into the uterus as well.

Damian: Right. Wow.

Andrea: We normally see more fertility challenges with a retroverted uterus, and we see a more common occurrence of things like sciatica as well.

Damian: Around the period time?

Andrea: Yeah, yeah. So that's cyclical sciatica.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: I think is a really big red flag, either endometriosis or retroverted uterus.

Damian: Okay.

Andrea: And we'll often see more like ovulation pain and normally more advanced endometriosis, I will see, a retroverted uterus as well.

Damian: Wow, this is big. I reckon people are going to be rewinding this and taking notes and going, oh, 15 seconds, 15 seconds. You know when you want the podcast to go back one minute, not 15 seconds at a time. I reckon that's what they're going to want to do to get all these little nuggets that you're sharing with us, Andrea. This is absolutely amazing.

Andrea: Thanks, Damian.

Damian: So it's pretty clear that there's a pelvic distortion component to what our female patients could be feeling if they're coming to see us with dysmenorrhea.

What are amenorrhea? Is that also similarly related or could that just be purely hormonal? And if it is purely hormonal, is that also under autonomic control?

Andrea: Well, the uterus and the ovaries are under autonomic control.

Damian: Full stop.

Andrea: So I think that if there's autonomic dysregulation, it's reasonable to see women with either heavier periods, more painful periods, or even absent periods. So, for example, and just to get like super nerdy, the uterus is innervated sympathetically by the uterovaginal plexus and parasympatheticly from S2 to S4 from the sacrum.

So that's why like big falls on the sacrum, any irritation of those nerves is obviously going to change that. And the reason that that is so important is because contraction in the uterus, so, for example, during childbirth or menstruation to expel the bladder or whatever we're trying to achieve there is a stop-go system. So we need that balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. Does that make sense? And I'll get to it. I'll cycle back to it amenorrhea in a second.

Damian: It does. Yeah. Yeah, it does. And I think it's good for everyone just to kind of...let's bring everyone back up to speed with that one, again, because you just called it a “stop-go system” so we're either going parasympathetic or sympathetic. Is what you're saying? It's on or off? Or maybe just explain that a bit better so that I can get my words right, too.

Andrea: Okay. So essentially, we need balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system to be able to control that properly. So for example, if the hypogastric plexus is stimulated too much, then we're getting intense contractions during the period, we're getting intense cramping, we're getting more excessive blood flow. Does that make sense?

Damian: It does. Yes.

Andrea: And the uterus is so important for even though it's not a hormone-producing organ, we need a functional uterus for proper ovarian function. And I think that this is so critical for women who may be considering, say, a hysterectomy because the blood supply, lymphatic flow, and nerve supply that goes to the ovaries goes to the uterus first and comes from the uterus as well.

Damian: Wow.

Andrea: And obviously our ovaries are our main hormone-producing organs or our primary sex organs in menstruating women. And then obviously, as we transition through that midlife time into perimenopause and menopause, our adrenal glands and our peripheral tissue takes over the production of those hormones, but during, obviously, puberty and our fertile years, our ovaries are responsible for that. And so we need that proper innervation for that proper control of the uterus to also control ovarian function to enhance hormonal production. Does that kind of make sense?

Damian: Unbelievable. Yeah, yeah, totally. Totally makes sense. I'm thinking, I'm stuck on the 75% of women have an anteverted uterus or...was it uterus, yes, anteverted uterus. I'm stuck on that. And the reason I'm stuck on that is because I think about that we have an increasing rate of weight gain, rate of weight gain, and we see a lot of obesity and that forward carriage of weight through the abdomen into the pelvis. Could that also be something that's related? And I want to go back to falls and slips and that sort of thing, accidents to the coccyx, but like these postural distortions as a result of where we carry weight or where women carry weight? Could that be related?

Andrea: Damian, absolutely and dramatically as well. We also see women who are overweight or obese have much heavier and often more painful periods because part of what happens within the uterus when you're menstruating is the uterine lining repairs itself almost instantaneously as we get that shedding. Whereas with the increased body weight, there's this increase in oxidative stress so that healing of that uterine lining is so much slower. So we get so much more bleeding, so much more pain, and that's related to obesity and it's related to that excess body tissue as well. So certainly there's a postural issue there. There's purely just a body tissue issue there that's driving that oxidative stress and everything else.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: But I find that some of my more obese patients struggle more with period pain because of purely that uterine position issue, and it's much harder to correct as well.

Damian: And could also be...that's going back to the biochemical thing, given that we know that body fat secretes interleukin-6 I think it is, and oestrogen, and there's a hormonal component of control with body fat, and there's got to be some kind of biochemical component to that as well as the postural and neurological distortion thing there. So kind of it's two-pronged, double pronged. We've got like a metabolic issue that needs addressing.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: So we've got to definitely make sure that we're helping our patients get the weight off and explain to them that this has hormonal influence, etc., etc. But also then explain to them that the weight itself and where it sits has an impact on the position of the uterus and the position of the pelvis, and therefore both things, like we're talking biochemical and neurological/structural could be influencing these patients' symptoms.

Andrea: Absolutely. And I sort of try to explain to my patients that excess body tissue is its own endocrine-producing organ. So this is where we're getting sometimes those toxic levels of oestrogen, for example, that's so unregulated and it's so difficult for the system to be metabolising when they are really overweight. So, obviously, diet and lifestyle and everything else that comes into play with looking after a patient holistically is critical.

Damian: Yes. Crucial. Absolutely crucial. I want to go back just a step, Andrea, you mentioned before falls on the coccyx. And, obviously, children fall all the time. But sometimes you hear of an injury that took place at the age of 8 years old where the little girl fell off or slipped off the seat of a bike and hit her coccyx on the crossbar of the bike and broke the coccyx, and then that's kind of people just go, “Oh, don't worry, the coccyx will heal itself.”

But could that be related to some of this dysfunction in the pelvis? And then, what would have happened had that been corrected earlier on, like if it was related?

Andrea: Oh, that's a really great example of that coccyx issue because normally once you fracture a coccyx particularly that kind of sits at that 90-degree angle anteriorly, that’s a pretty tricky thing to heal. And it's kind of stuck like that, really. And my understanding of that I'm thinking of those sacrotuberous ligaments that obviously anchor into the base of the coccyx and then down to the base of the pelvis as well. And when all of that is disrupted, they're part of the stabilising structure for the actual sacrum. And so when that sacrum is distorted and particularly if you've got like rotational issues for the sacrum, that's also creating that rotational distortion pattern through the uterus too, which is going to be affecting, obviously, uterine position, but also blood nerves and lymphatic flow to that area.

And this just came to my mind, so I'm just going to share it with you. But the sacrum means “sacred” or “holy bone.” And I just love that because I think it's the key stone to the all, the way I see it, all of that pelvic health as well. So if we've got a little girl who had a big fall when she was really, really young, and her body has...there hasn't been sort of any ways to address that, then we know that that's certainly going to be turning into a chronic issue. And the longer something has been there for, the more adaptation that the body has created to overcompensate for that, really. And normally with coccyx issues, you'll see either a dramatically anterior or posterior sacrum in my experience. That's just what I've seen in my patients.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: And when I've looked at X-rays and those sorts of things for patients as well who've had those big coccyx injuries. And the longer it's been there for, the more adaptations, so the harder it is and the longer it's going to take to change.

Damian: Well, that kind of makes sense. So we then start to talk about the link between an acute dysfunction and a chronic dysfunction, the length of time between something being checked and then brought to attention and regulated or managed really well, could have a significant role to play in the reproductive health and definitely, the reproductive health of that particular person, that young girl, even the young lady.

Andrea: Yeah, absolutely. We know that, for example, a retroverted uterus is a risk factor for infertility and a pelvic distortion that might happen or pelvic, like organ distortion that might happen in, say, something like endometriosis, for example. We know that that is a risk factor and it's called the so-called pelvic factor that increases the risk of infertility for patients with endo.

Damian: Yeah.

Andrea: And that's observed, like a really common observation in laparoscopic surgeries as well. So those adhesions that form that distort the position of the uterus and can also distort, for example, the sacral position can change how the oocyte is released in the ovary. It can change how the ovum is actually picked up in the fallopian tube, and it can impair that ovum transport as well.

And I think that they even showed...there was a study that showed that in monkeys, which is probably, I guess, the closest thing to a human study really that in monkeys with endometriosis that it showed that their fertility was impaired because of those pelvic adhesions and because it also affected like follicle rupture. And that's all because of that pelvic distortion pattern.

Damian: Yeah. I'm blown away that monkeys get endometriosis as well.

Andrea: I know. Isn't that terrifying?

Damian: That's got me.

Andrea: I can't remember if it was...and this is a long time ago that I read this, but I'll have to dig it out. I can't remember if there was a causation…that will given endometriosis essentially in the first place, and then that was assessed.

Damian: Okay. Unbelievable. Now, we haven't got a whole lot of time to go but I think we could probably make this into a...we could do a second part to this particular interview. And I reckon it might be worthwhile because there's a lot more information that I think we need to get through. Because we've only done two of the five S's so far. There's a lot more we got there.

Andrea: Oh, I know.

Damian: So we did talk about cortisol. And you were touching on a new, I suppose, approach to the understanding of what could be going on. And that's unregulated inflammation as a result of hypercortisolemia. And I think that's where you're going with that. Is that something that we've got time to discuss now or should we come back to that in another episode?

Andrea: Oh, Damian, that's such a good question. So there is some new... Let me get started and then you can tell me if you want to go down that rabbit hole.

Damian: Okay. All right.

Andrea: I might drift a bit there because what I really want people to understand is that there is a direct connection between pain and hormones.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: And there's this saying that I have is that “Adequate pain control cannot be achieved without hormonal homeostasis.” So hormone levels actually serve as biomarkers of uncontrolled pain. And, personally, clinically, in practice, I actually find pain so boring. It doesn't interest me at all but I know it's certainly interesting for a lot of patients.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: But now that I've sort of looked at the other dimensions of pain, I find it a hell of a lot more fascinating. And there is this new emerging research that shows that major pain control mechanisms of each sex hormone in the steroidogenic pathway has actions of pain modulation, so including things like immune modulation, anti-inflammatory actions, cell protection, tissue regeneration, even glucose control, which is affected by pain as well. And that hormones also, like particularly oestrogen, they modulate the central nervous system receptors and nerve conduction too. So this is certainly very much a two-way street.

Damian: Wow.

Andrea: And if we look at, say, I think a really great example of this is how oestrogen can be either pro-inflammatory and pro-nociceptive, or it can be anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive, depending on its balance.

Damian: Yes. Okay. So the balance of oestrogen versus progesterone and testosterone, for example, or the balance of oestrogen versus cortisol and adrenaline. Or is it all of it? Like are we talking about this big HPA...?

Andrea: All of it. Yeah, because we know that obviously neurohormones acts independently.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: And it is that, I think we always refer to it as that “hormonal symphony orchestra of balance,” and cortisol is certainly the conductor. I think I heard someone say it's the conductor of that orchestra, which I think is really accurate.

But oestrogen is either a pro or anti-inflammatory nociceptive, just depending on the phase of the cycle and its balance, and obviously, the body's ability to metabolise it correctly. Whereas testosterone appears to be pain protective. So it has mostly anti-nociceptive actions and can downregulate the activity of oestrogen receptors in the brain.

So I think this is super important for men as well because that means that low or deficient testosterone levels are linked to higher risks for all sorts of chronic pain states, an inflammatory like nociceptive nervous system stuff that goes on. But also for men who may be aromatising testosterone into oestrogen too quickly, that would be part of why we see those painful inflammatory conditions in those men with lower pain thresholds. Damian, do you see that in practice as well?

Damian: Jeez. Yeah, totally. You definitely see some men come into the practice. They may be carrying a bit more weight in around the middle areas of their belly.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: And we do know that men can carry a lot more visceral fat to the tune of say 20 kilograms more than what women can and that is a huge hormone impacter and influencer. And definitely you see those men who are very sensitive to pain, it could be a tiny little thing that's not right and they're in a lot of pain. So, yeah, I definitely see that in practice, no doubt about it. And it makes a lot of sense too, with the women that are hypersensitive, sometimes you could have an obese lady lying on the table and you just lay your hand on that person and she's jumping off the table.

Andrea: Yes.

Damian: And so there's that hypersensitivity that you kind of go, "Ah, this is weird," but it just kind of makes sense with this new emerging research that you're talking about. Fascinating.

Andrea: Yes. And when it comes to cortisol, Damian, without going into, there's so much there around cortisol and how that whole lot pituitary-adrenal-ovarian-thyroid axis that’s sort of stimulated with stress and pain. But in this stimulation phase of severe pain, hormone levels initially go up. But if the pain persists or cortisol goes up in response to that pain, there's a threat, and that's what that pain response is.

Damian: Yes.

Andrea: And if the pain persists, that hormonal system is usually unable to tolerate the stress of the pain. So then we get this reduction in that, which then gives us this reflexive low cortisol picture, which is actually the more serious hormonal complication of severe chronic pain. And that's its negative impact on cortisol.

And women with chronic pelvic pain, for example, actually demonstrate low cortisol levels rather than those with acute pain who originally had high levels. So women with chronic pelvic pain have hormone levels that are consistent with prolonged consistent stress. I just find that so interesting. Yeah.

Damian: Far out, this is so unbelievable. This is so unbelievable. There's a lot more that I'd love to discuss with you. And I think that we could probably make a second episode of this, and I'll go to the bosses and I'll ask them, "Can we get Andrea back on for another one?" And if you're listening to this and you're wondering, "Oh, my gosh, there's so much more that I want to learn from Dr. Andrea. Please do another podcast," then send us some feedback, let us know.

But I think, Andrea, we've come really close to time and I'm going to have to call it on this one because there's still three S's that we've got to get through. And I just know there's so much that we can cover, including timing and why do people go to a chiropractor, and why do they go for a long time, or is it just a short-term thing? And so I really want to cover that off.

But I think we should, to do that justice, come back and do that in another podcast. Will you come back on and do another podcast with me, Andrea?

Andrea: Oh, Damian, I would love to. Yes.

Damian: That'd be great. That'd be great. Well, I think we'll leave it at that for today because we're going to run out of time and we'll bring you back on for a part two, Andrea. And I know that people will be chomping at the bit to listen to you again.

But, Andrea, that information today was unbelievable. Thank you so much for joining us on FX Medicine. It's been an incredible, incredible interview. Thank you, Andrea.

Andrea: Damian, thanks so much for having me. It's a pleasure.

Damian: To get more information about Dr. Andrea, head to dr.andrea.com.au or wellnesswomenradio.com.

Thanks, everyone, for joining us today. Don't forget that you can find all the show notes, transcripts, and other resources on the FX Medicine website. I'm Dr. Damian Kristof. Thanks for joining us.

About Dr. Andrea Huddleston

Dr Andrea Huddleston is a women’s health, natural fertility expert and integrative chiropractor practising in Perth. She is the co-host of the award winning, top-rated podcast Wellness Women Radio and is affectionately referred to as ‘the period whisperer’ by her patients! In addition to her chiropractic degrees, Dr Andrea holds two post graduate, masters degrees in Women’s health medicine and reproductive medicine.

She is a leader in women’s health, sought after presenter, avid coffee addict and crazy dog lady!

Instagram: @drandrea.xo | Facebook.com/theperiodwhisperer

www.thewellnesswomen.com.au | https://podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/wellness-women-radio/id1037216440

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.