Introduction

Echinacea has been the subject of over 600 scientific journal articles. The majority of the studies, meta-analyses and systemic reviews relate to its action on the immune system and its effect on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs). Even with this vast number of studies, the evidence for echinacea’s efficacy on URTIs remains controversial. The world’s foremost authority on echinacea, Dr Rudolf Bauer, states this is because researchers have failed to use standardised, consistent and researched echinacea extracts.[1] Until such extracts become more widely used by researchers, echinacea research will continue to produce inconsistent results in URTIs and other conditions.

Echinacea: More than a Respiratory Remedy?

Vaginal Candidiasis

Taking Echinacea purpurea orally in combination with a topical antifungal cream is effective in treating Candida albicans infection, according to one early study. At six months, the recurrence rate was 16.7% compared to 60.5% when using the cream alone.[2,3] An earlier animal study showed E. purpurea to enhance immune activity against candida.[4] In 2002, an in vitro study confirmed echinacea’s ability to inhibit the growth of various yeast strains including C. albicans.[5] Further controlled human trials would confirm echinacea’s effectiveness in candidiasis.

Herpes Simplex Virus

An in vitro study, looking at echinacea’s effect on herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, demonstrated its antiviral properties. E. purpurea was one of two species shown to be the most potent inhibitors of HSV.[6] A previous in vitro trial showed an indirect effect through the stimulation of interferon (alpha and beta).[7,8] However, the use of echinacea in the treatment of frequently recurrent genital herpes has no benefit, according to current research. In a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial involving 50 patients, there was no statistically significant benefit after taking 800mg of a specific patented echinacea product, twice daily for six months.[9]

Autoimmune Idiopathic Uveitis

One condition with seemingly unequivocal positive results with echinacea is low-grade autoimmune idiopathic uveitis. According to the Merck Manual "uveitis is inflammation anywhere in the pigmented inside lining of the eye, known as the uvea, or uveal tract" and can damage the eye permanently causing long-term complications such as swelling of the macula, glaucoma, and cataracts.[10] An Australian study showed anterior uveitis to be idiopathic in 52% of the cases assessed with the peak age of onset between 30 and 40 years. Patients with posterior uveitis presented a decade earlier.[11]

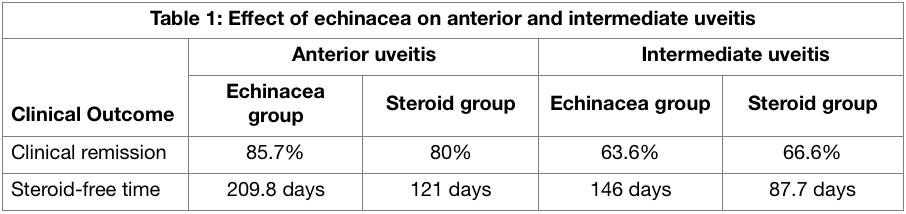

In 2006, a pilot study demonstrated that in 51 patients treated with both E. purpurea and steroids (rapidly tapered off) or the steroids alone, E. purpurea was of greater benefit, with no side effects. The clinical remission period was longer in anterior uveitis and the length of time patients did not require steroids was considerably longer in both the anterior and intermediate uveitis groups, as summarised in Table 1.[12]

When combined with propolis and vitamin C, echinacea decreased the incidence and severity of URTI, including acute otitis media, tonsillopharyngitis and pneumonia, in 430 children aged one to five years. The researchers also found a decrease in the total number of days of fever, antipyretic use, and antibiotic use; unscheduled visits to the physician; and absence from day care or kindergarten.[13,14] The mechanism of action of echinacea in uveitis is unknown. However, the alkylamide constituents, found in the root, inhibit tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) gene expression through the cannabinoid CB2 receptor. This is highly relevant as TNF-alpha is a major mediator of inflammation and cell death.[8,12]

Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

However, a recent randomised, controlled trial showed an alcohol extract of E. purpurea administered to children for 10 days, at the first sign of a common cold, did not decrease the risk of acute otitis media. This study used a combined treatment of osteopathic manipulation, which was also of no benefit. The echinacea used was a 1:1 weight-to-volume 50% ethanol liquid extract of the fresh roots and dried mature seeds of E. purpurea. The dose given was 0.5mL orally thrice daily for three days at the onset of cold symptoms, followed by 0.25mL orally thrice daily for seven more days.15 It is worth noting that the fresh aerial part of the plant was not used and the dose given was low, especially for the older children.

Leucopaenia

A small number of studies support the use of echinacea in radiation-induced leucopenia,16 however, specific recommendations cannot be made due to the existence of conflicting results.

Traditional Uses of Oral Echinacea

|

The Answers to Inconsistent Echinacea Research

The three species of echinacea used medicinally, E. purpurea, E. angustifolia and E. pallida, contain an assortment of chemical constituents with pharmacological activities. The parts of the plant commonly used are the aerial portion, the whole plant including the root, and the root itself. The most important constituents are:

- Polysaccharides — found in both root and aerial parts.

- Cichoric acid and other caffeic acid derivatives — found abundantly in the root and aerial parts of E. purpurea.

- Alkylamides — this is the cause of the mouth tingling sensation; found in the roots of E. purpurea and E. angustifolia.

- Flavonoids, essential oils and glycoproteins — found in both root and aerial parts.[1,8]

Dr Rudolf Bauer, a German-trained doctor, has conducted more research on E. purpurea than any other person, adding to the work of other researchers who have found E. purpurea to have the strongest effect on the immune system.[17]

Despite worldwide extensive research into echinacea, the active components, optimal doses of these components, and the in vivo effect remained elusive for many years until Dr Bauer and fellow researchers conducted a number of animal studies that lead to the following conclusions:

- Echinacea preparations containing optimal concentrations of cichoric acid, polysaccharides and alkylamides are potentially effective in stimulating an in vivo, nonspecific immune response.

- The standardised level of each of the top three constituents listed above, and their ratio, defines the effectiveness of the product as a whole.[1,18,19]

When Dr Bauer analysed various E. purpurea products in the marketplace he found that the two factors above were not being met. He found remarkable variances in cichoric acid and alkylamides levels in products from the same manufacturers, and even in the same batches.[1,20]

Variances in active constituents in echinacea products

Additionally, the preparation of the echinacea plant extract has a significant effect on its activity. The drying of E. purpurea can cause a loss of up to 30% of active compounds.[1] Cichoric acid is labile and drying decreases its concentration, especially in aerial sections.[21] Reduction in alkylamides levels is also evident in aerial parts, but also occurs in the root.22 Finally, loss of activity can occur rapidly if the fresh plant is not processed immediately after harvesting—as much as 80% of active constituents, such as cichoric acid and alkylamides, may be lost.[1]

Therefore, the ideal echinacea product includes fresh root and aerial parts, processed appropriately to avoid loss of constituents, and standardised to the correct level and ratio of polysaccharides, cichoric acid, and alkylamides, without loss of other constituents.

Conclusion

The natural inconsistencies in the levels of active constituents in different echinacea extracts, and the possible differences due to manufacturing processes, will continue to confound the evidence for echinacea, and hinder research advancements in areas other than respiratory health. Presently, we know that those with weak immune systems prone to infections and those under constant stress or exposure to viruses can take echinacea daily.[1] Until researchers, manufacturers and suppliers can show consistency and document the levels of active constituents in their extracts, echinacea will not be used to its full potential.

Future high-quality research, conducted by authorities such as Dr Rudolph Bauer, will provide more answers into the added benefits and potential of echinacea. Until then, with its high safety profile, echinacea may only be ‘trialled’ in clinical situations for conditions other than URTIs.

References

- Murray M. The immune factor. Canada: Mind Publishing Inc, 2001.

- Coeugniet EG, Kuhnast R. Recurrent candidiasis: adjuvant immunotherapy with different formulations of Echinacin. Therapiewoche 1986;36:3352-3358.

- Echinacea. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database. Viewed 6 May 2016 [Link]

- Steinmüller C, Roesler J, Gröttrup E, et al. Polysaccharides isolated from plant cell cultures of Echinacea purpurea enhance the resistance of immunosuppressed mice against systemic infections with Candida albicans and Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Immunopharmacol 1993;15(5):605-614. [Abstract]

- Binns SE, Purgina B, Bergeron C, et al. Light-mediated antifungal activity of Echinacea extracts. Planta Med 2000;66(3):241-244. [Abstract]

- Binns SE, Hudson J, Merali S, et al. Antiviral activity of characterized extracts from echinacea spp. (Heliantheae: Asteraceae) against herpes simplex virus (HSV-I). Planta Med 2002;68(9):780-783. [Abstract]

- Beuscher N, Bodinet C, Willigmann I, Egert D. [Immune modulating properties of root extracts of different echinacea species.] Z Phytother 1995;16(3):157-166.

- Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

- Vonau B, Chard S, Mandalia S, et al. Does the extract of the plant Echinacea purpurea influence the clinical course of recurrent genital herpes? Int J STD AIDS 2001;12(3):154-158. [Abstract]

- Cunningham Jr ET. Uveitis. The Merck Manuals Online Medical Library: home edition. Merck Research Laboratories, 2008. Viewed 6 May 2016. [Link]

- Wakefield D, Dunlop I, McCluskey PJ, et al. Uveitis: aetiology and disease associations in an Australian population. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1986;14(3):181-187. [Link]

- Neri PG, Stagni E, Filippello M, et al. Oral Echinacea purpurea extract in low-grade, steroid-dependent, autoimmune idiopathic uveitis: a pilot study. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2006;22(6):431-486. [Abstract]

- Cohen HA, Varsano I, Kahan E, et al. Effectiveness of an herbal preparation containing echinacea, propolis, and vitamin C in preventing respiratory tract infections in children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158(3):217-221. [Abstract]

- Carr RR, Nahata MC. Complementary and alternative medicine for upper-respiratory-tract infection in children. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2006;63(1):33-39. [Abstract]

- Wahl RA, Aldous MB, Worden KA, et al. Echinacea purpurea and osteopathic manipulative treatment in children with recurrent otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2008;2;8:56. [Full text]

- Braun L, Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence-based guide, 2nd ed. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2007.

- Bodinet C, Willigmann I, Beuscher N. Host-resistance increasing activity of root extracts from Echinacea species. Planta Med 1993;59(7 Suppl):A672-A673.

- Goel V, Chang C, Slama J, et al. Echinacea stimulates macrophage function in the lung and spleen of normal rats. J Nutr Biochem 2002 Aug;13(8):487. [Abstract]

- Goel V, Chang C, Slama JV, et al. Alkylamides of Echinacea purpurea stimulate alveolar macrophage function in normal rats. Int Immunopharmacol 2002;2(2-3):381-387. [Abstract]

- Bauer R. Standardization of Echinacea purpurea expressed juice with reference to cichoric acid and alkamides. J Herbs Spices Med Plants 1999;6(3):51-61.

- Stuart DL, Wills RB. Effect of drying temperature on alkylamide and cichoric acid concentrations of Echinacea purpurea. J Agric Food Chem 2003;51(6):1608-1610. [Abstract]

- Kim HO, Durance TD, Scaman CH, Kitts DD. Retention of alkamides in dried Echinacea purpurea. J Agric Food Chem 2000;48(9):4187-4192. [Abstract]

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.