How confident are you in the short and long term health implications of a gestational diabetes diagosis?

In this episode, registered dietitian, nutritionist, and certified diabetes educator Lily Nichols shares her expertise on managing gestational diabetes. Lily covers how gestational diabetes is different from type 2 diabetes, why blood sugar control is so important in pregnancy and why guidelines for pregnancy nutrition may not yeild desirable clinical outcomes.

Covered in this episode

[01:05] Welcoming Lily Nichols

[01:46] Dietetics: USA vs Australia

[06:25] Today’s topic: gestational diabetes

[08:15] Do women with gestational diabetes go back to normal after giving birth?

[10:35] Is gestational diabetes is different from type 2 diabetes?

[13:36] Blood sugar parameters in pregnancy

[16:54] Diagnosing gestational diabetes

[20:57] Comorbidities

[23:14] Concerns with birth weight

[26:57] Dietary intervention in mothers with gestational diabetes

[32:31] The standard American/Australian diet

[36:26] Is it hunger, or emotional craving?

[40:53] Changing eating habits

[43:15] Nutrients that impact glycaemic control

Andrew: This is FX Medicine. I'm Andrew Whitfield-Cook. Joining us on the line today from Washington State, USA is Lily Nichols who's a registered dietitian and nutritionist, a certified diabetes educator, researcher, and author with a passion for evidence-based prenatal nutrition and exercise. Her work is known for being research-focused, thorough, and unapologetically critical of outdated dietary guidelines. She's the author of two best-selling books, "Real Food for Pregnancy" and "Real Food for Gestational Diabetes." That's what we'll be talking about today on FX Medicine. Welcome, Lily.

Lily: I appreciate the invite. Thanks for having me.

Andrew: Lily, first, though, before we get into the subject matter, would you mind just taking us through the landscape, if you like, of a registered dietitian in the U.S. because I think there might be some similarities to the Australian landscape here.

Lily: Sure. So registered dietitian is probably one of the only nutrition professionals that's officially recognised as being "legitimate" by the medical establishment, meaning we have like pretty regimented training, standardised training that you have to go through. So you have to have a four-year education in nutrition and undergraduate education, then do a formal internship involving some work in a clinical or hospital setting, and then pass the national examination. So it's good in some ways that it's standardised, it makes sure people have a baseline of knowledge. And then in other ways, it has room for improvement because, by default, what we're taught is, you know, the status quo for nutrition are the government dietary guidelines, which I think we both agree have room for improvement.

Andrew: Did this change as you started your learning, compared to when you came out? Did the shift happen then or did the realisation that these guidelines were outdated happen after you were registered?

Lily: Well, actually, it's a funny question because I did not go into my training with rose-coloured glasses. I had already been introduced to ancestral nutrition via Weston Price's writing and "Nourishing Traditions" by Sally Fallon before I even went through my undergrad. And so my time spent in university was actually me taking advantage of the access we had to medical journals and trying to understand why there was such a discordance between what I was learning in my conventional training…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …and what these real food, ancestral, paleo nutrition, sort of, people were saying. And funny enough, maybe not funny enough, but a lot of times I found the evidence is actually more in favour of an alternative approach, not what I was learning in the guidelines.

Andrew: Wow.

Lily: So if anything, I think I came into my nutrition training from a very different place than most dietitians were. I wasn't seeing what I was being taught as, you know, etched in stone, you know, perfect, infallible doctrine. I was looking at it as, this doesn't make sense in the context of the way that human beings ate thousands of years ago…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …even hundreds of years ago.

Andrew: So you were already woken up, eyes wide, before you went in there. How were you viewed by your colleagues?

Lily: Well, I think you learn in your training to smile and nod a lot.

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: So I kind of remember I didn't get the best grade on a presentation I did in my undergrad where I was looking at Splenda, and like at the time, you know, you have to take organic chemistry in your undergrad. I'm like, "This is a chlorocarbon, people, like, this cannot be good for us."

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: Yeah, my professors didn't really like my presentation, even though I backed all my things up with evidence. I didn't get a bad grade, I just didn't get as good of a grade as I would have if I had just been doing a presentation on, like, fibre is good for us or something really boring.

Andrew: Yeah, that's right.

Lily: As far as like professional colleagues, yeah, I think you have to learn...I ended up, sort of...I guess you get a little bit jaded at a certain point in your training where you're like, "Everything I'm learning is..." It's not that it's all BS, there's just like a significant proportion of what I'm learning that I know is not true, and that is frustrating. But I learned to view my training for what it was.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: You kind of have to understand the box that the field is built inside of to know how to get out of the box. And the only way that you're going to be able to, you know, rationalise or negotiate with the other side is understanding where they're coming from. So I just did a lot of observing, and a lot of smiling and nodding, and a little bit of pushing here and there when I knew I could…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …but I wasn't really about like, you know, starting fights with people over specific topics. I just certainly was not...you know, I wasn't swallowing the pill of 'I need to, you know, have cereal and skim milk for breakfast,' you know?

Andrew: Yeah, let's get back on to the topic, gestational diabetes. Now, this is a burgeoning problem. Tell us a little bit about like, firstly, what is it and give us some statistics from the US.

Lily: So gestational diabetes is elevated blood sugar during pregnancy. It can be elevated blood sugar that was first recognised or first developed during pregnancy, which can mean two different things because you start to incorporate the whole epidemic of pre-diabetes. Pre-diabetic women coming into pregnancy already with insulin resistance are probably going to have some sort of blood sugar issues in pregnancy as well. But you would still probably call that gestational diabetes because you maybe first identified it in pregnancy. It can also be described as carbohydrate intolerance during pregnancy, which I think is very telling…

Andrew: Ah.

Lily: …because it's explaining exactly what happens physiologically. Your body has a lessened ability to tolerate large amounts of carbohydrates without having elevated blood sugar as a result. So regardless, there's higher blood sugar than you would have observed in normal pregnancy when GD is recognised. As far as how common it is? It depends on how you diagnose it. If we follow the, like, World Health Organisation recommendations and the whole International Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group recommendations, and I'm pretty sure it's how they diagnose in Australia…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …pretty much anywhere outside the US uses the updated guidelines, it can affect up to 18% of pregnancies. So it's actually the most common pregnancy complication by far.

Andrew: Most pregnant women ostensibly go back to normality after experiencing gestational diabetes. But is this true?

Lily: So what's interesting about gestational diabetes, and I think what's tricky about it, is that technically most women actually return to somewhat normal glucose tolerance, at least as identified in the early postpartum days, about 90% will actually have normal blood sugar when they're tested early postpartum. Usually 6 to 12 weeks. However, over the long term, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes can be upwards of 70%…

Andrew: Oh, wow.

Lily: …within the first 5 years of having your baby.

So just because blood sugar might trend back down in the early postpartum phase, gestational diabetes, it's like the warning light coming on in your car. There is something going on with your glucose regulation, whether it's an inability for your body to pump out large amounts of insulin that's needed in pregnancy. So like the latter half of pregnancy, your body might be producing double or triple the amount of insulin. So it could be an inability to adapt to that.

It could be that your body has high levels of insulin resistance, which I actually see more commonly than it being a total lack of your pancreas adapting insulin production. So your body's not responding to it well, which isn't necessarily purely a phenomenon of pregnancy. So a lot of this is...what we're seeing with the rates of gestational diabetes rising right alongside rates of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes is that it's all related physiologically.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: So there is a much higher risk of having blood sugar issues later on. And so they do recommend checking your blood sugar at least annually. I think it would be ideal to have people occasionally monitor at home so you can identify problems earlier than that, but they do recommend checking on a regular basis to see if...they call it converting to type 2 diabetes in the literature.

Andrew: Right, so are there any differences with gestational diabetes or is it exactly the same as type 2 diabetes just in pregnancy?

Lily: Well, it's not exactly the same because pregnancy itself is putting a big strain on your blood sugar and insulin regulation system. So, I already mentioned your body has to produce a lot more insulin in pregnancy, but you also become more insulin resistant as a result of placental hormones as well as the weight gain that naturally accompanies pregnancy. So it's kind of as if it's working against you a little more than not being pregnant. However, some people will take this conversation in the direction of, well then, if all of these things are working against you in pregnancy, then gestational diabetes is a made-up diagnosis.

But actually, despite all of these things happening, in women who do not develop gestational diabetes, their blood sugar actually runs about 20% lower than people who are not pregnant. Like, your body tries really hard to keep your blood sugar levels low during pregnancy. The change in insulin resistance, for example, is a sort of biological built-in mechanism to try to shunt as many nutrients to the baby as possible. Like, the maternal body does not want to be greedy and eat up all the nutrients, it wants to send them to the baby, thus the insulin resistance that is developing.

But if everything, you know, is working as it's designed, you actually don't end up with elevated blood sugar, you actually end up with lower blood sugar, which is why, like, the pregnancy goals for blood sugar regulation are significantly lower than in a non-pregnant adult with type 2 diabetes.

Andrew: That's really interesting to me because, you know, there's a shift in the fermicutes, the basically carb harvesters of the human microbiota during pregnancy. One would therefore simplistically assume that it's going to harvest more sugar for the mom. Not so. This is really interesting, so the mother, right from the word go, is sacrificing themselves just like they will throughout their whole motherhood for their child.

Lily: In a way, yeah. Actually the pancreas starts adapting to pregnancy very early on in the first trimester. You don't yet have a crazy amount of insulin resistance happening because the placenta is like just developing, you also haven't gained as much weight yet and all that. But the pancreas has already started adapting, your beta cells start reproducing, and you start producing more insulin starting very early on in pregnancy. It's like it knows what's happening it knows what's impending down the line.

Andrew: Yeah. Now you've said the maternal blood sugars are lower. Why do these matter so much during pregnancy given, obviously, you know, a normal sort of range? What's so critical about the blood sugar range during pregnancy?

Lily: So what we've found, some of the best data we have on pregnancy outcomes related to blood sugar comes from a study called the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Study, or HAPO for short, which was over 25,000 women from I believe it was 9 different countries. And they matched blood sugar, average blood sugar levels to all these different outcomes in babies. So some of the most classic things they worry about with gestational diabetes is that the baby could grow too large. They call this macrosomia.

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: And it's not necessarily because they're exuberantly healthy but because they've been exposed to consistently high blood sugars throughout pregnancy, which then results in increased fat deposition and actually can result in, like, less good outcomes for the baby. Like under development, can also affect the development of the pancreas, can affect the width of the shoulders so they can be more likely to get stuck in the birth canal, which is called shoulder dystocia. So there's a number of things that can happen as a result of that.

For me, actually, I think the most concerning thing about gestational diabetes that's not well controlled, is the effect on the baby's pancreas and the programming, the epigenetic programming of their metabolism. And we see from research pretty consistently that elevated blood sugar levels during pregnancy triggers the foetal pancreas to produce excessive amounts of insulin and that can affect their blood sugar regulation for the rest of their life, where children who are born to mums who had uncontrolled gestational diabetes face a six-fold higher risk…

Andrew: Wow.

Lily: …of developing type 2 diabetes by the time they turn 13.

Andrew: Oh, my goodness.

Lily: So this whole, huge, you know, explosion we're having in childhood obesity and childhood diabetes is, in part, related to what they were exposed to in-utero. And that's the part that we have the ability...well, a lot of it, we have the ability to change the outcome. But that, I think, is probably the most important outcome that we could change.

Because, you know, issues affecting a baby immediately after birth, I mean, yes, they're not ideal, but it's seen as a temporary thing. And this shows us that no, actually, this can have long term impacts.

Andrew: Absolutely. I mean, not just are we setting the future generations up for, you know, there's the next generation of diabetics, but right from the word go, you've got adverse outcomes. Like even if it's obesity, cardiovascular changes, weight gain right down to body image and bullying.

Lily: Right.

Andrew: That's really amazing.

But I guess firstly, we've done with a brushstroke, if you like, over how diabetes is diagnosed. But what tests do you use? Do you use HOMA-IR to figure out if you have gestational diabetes, do you use other tests? Obviously, we're looking for protein, we’re worried about preeclampsia, things like that. What do you look at when you see a mum come in?

Lily: Well, it would be fabulous if they use HOMA-IR or any marker of insulin production. They're looking purely at blood sugar levels...

Andrew: That's it?

Lily: ...to diagnose gestational diabetes. Yeah, they're not looking at insulin, which is very silly because that's a lot more telling of insulin resistance, right?

So usually how they're diagnosing is with a glucose tolerance test. And in lieu of that, there are some other alternative strategies which are less commonly used, but I think have, you know, merit to their use, which could be home glucose monitoring, it could be hemoglobin A1C in the first trimester. Some places will just check fasting glucose. Some people will use like a test meal in place of doing the official glucose tolerance test, but it's typically just looking at glucose levels alone.

Andrew: Can I ask you about HbA1C? It took a long while for the States to come away from fructosamine, which, forgive this simplistic overview, my understanding is that it's a shorter-term average, like a one-and-a-half to two-month average, whereas HbA1C is around about that three-month average. Is that correct?

Lily: Correct.

Andrew: What are the differences in those tests? And does fructosamine actually have some advantages?

Lily: Actually, there is some research on fructosamine and gestational diabetes being a more accurate marker of blood sugar balance...

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: ...and blood sugar control. I have not seen fructosamine being used as an alternative diagnostic standard…

Andrew: Oh, okay.

Lily: …whereas A1C has more commonly been studied on that.

Andrew: Right.

Lily: And, for example, an A1C of 5.9% or greater in the first trimester, women who have a marker of 5.9% or greater, if they go on to do a glucose tolerance test, the chances that they'll fail the glucose tolerance test is 98.4%.

Andrew: Whoa.

Lily: So A1C can be a very good marker of, you know, blood sugar regulation, insulin resistance issues later on. And you can also...since you use it in the first trimester, you can identify blood sugar issues very early on in pregnancy instead of waiting until 24 to 28 weeks when like two-thirds of the pregnancy is over to identify an issue. Because really what we're seeing is that there's a lot of...it's really undiagnosed pre-diabetes.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: I mean, if your A1C is high, above 5.7 in the first trimester, that's the marker of your blood sugar balance pre-pregnancy. And that's really what we're catching when we use A1C at that time point.

I do always like to give the caveat that you can't use A1C as a diagnostic measure later in pregnancy because you're...you know, if you think about what A1C actually is measuring, glycated hemoglobin, like how much of your red blood cells have been sugar-coated, essentially.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: Your red blood cells turnover quicker in pregnancy, your blood is also more dilute, and therefore A1C naturally tends to be lower as pregnancy progresses…

Andrew: Right.

Lily: …so it's not going to be a super accurate marker later on.

Andrew: How very interesting.

Lily: But in the first trimester when you haven't had a huge increase in blood volumes, the huge increase in red blood cell turnover yet, it is still useful.

Andrew: Yeah. What about comorbidities?

Lily: Well, blood sugar is related to so many things. So if we're talking just specifically about what's happening in pregnancy, your blood sugar and your blood pressure tend to be correlated.

And so you tend to see higher rates of preeclampsia and high blood pressure in pregnancy develop in mothers whose blood sugar isn't well controlled. And interestingly, I've had the experience clinically of working with clients with preeclampsia who supposedly don't have gestational diabetes. And when we do a diet recall and talk about what they're eating, it's like all carbohydrates…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …like it's not very good, a very good quality, a very well-balanced diet. And you start shifting those foods out and being conscious about carbohydrates, essentially giving the women with preeclampsia a gestational diabetes, lower-carb, gestational diabetes plan…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …and their blood pressure gets better, right?

Andrew: Right.

Lily: So it's all related.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: Yeah, and then you also...as far as like birth outcomes, there tends to be...Because the babies tend to but are not always bigger, there tends to be a higher chance of birth injuries, there can be a higher chance of C-section, which part of that is, you know, provider bias.

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: But that is something that's related.

There tends to be a higher rate of cholestasis, so gallstones. So there's definitely some things that can be related to the blood sugar issues. Although just to not make this all doom and gloom, I actually hear from a lot of people who end up having healthier pregnancies because they got a diagnosis of GD and because they started eating better and because they got their blood sugar better controlled.

Where, you know, I've had women who say, you know, "I had 3 pregnancies, I gained 60 pounds each time." And then their fourth pregnancy, they get a diagnosis of GD and change their diet and they're like, "Miraculously, I gained 25 pounds this time, and I felt great. And I just have so much more energy," you know.

Andrew: Wow.

Lily: So, sometimes the diagnosis actually can work in your favour and be a silver lining.

Andrew: Yeah, so it's like the call to action, if you like.

Lily: Right.

Andrew: Can you explain to us just this thing about birth weight, I sometimes get confused. The obvious thing for me would be a larger birth weight baby with gestational diabetes. But I've also heard, not necessarily with GDM, but with other conditions, this concern about lower birth weight babies. You know, a failure to thrive sort of thing. Where does this sit?

Lily: It's tricky because birth weight is kind of on a spectrum and there can be many possible reasons that a baby is growing to a particular size or not. I mean, it can be genetic, the height and weight of the parents can play a role. You know, some families just literally grow big babies…

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: …so they're not necessarily unhealthy. The concern with GD and its higher risk for macrosomia specifically in, sort of, a discordance in growth.

You can actually see it in third trimester ultrasound, you can see a thicker fat pad, especially in the abdominal region, in babies of mothers who don't have very good blood sugar control.

Andrew: Right.

Lily: Actually, in practice when I worked with a perinatologist, we would use that as a proxy for if we needed to tighten up our blood sugar goals for a particular person, if there was signs of macrosomia and higher percent...like an unnaturally high-percent body fat.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: Obviously, we're all supposed to some body fat.

The issue with a baby potentially not growing big enough or having failure to thrive, interestingly, like, the tighter glycemic control that you get, you're going to have, by default, a higher percentage of small for gestational age babies. Or smaller than expected babies. You're also going to have a smaller rate of macrosomia as well.

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: And so there's kind of this trade-off that's always...you know, people are back and forth in the research. Should we call for stricter glycaemic targets or not?

You know, a part of it could be if women are being overly restrictive with their diet, and I personally see this a bigger problem with people following the conventional recommendations, which are very high carb. I mean, there are a minimum of 175 grams of carbohydrates per day…

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: …to a woman who has carbohydrate intolerance in pregnancy. So just sort of think about how nonsensical that sounds.

If you're giving somebody, you know, 50, 60, 75 grams of carbohydrates per meal, what's going to happen? Her blood sugar is going to go too high. But at the same time, she's been told if she's following conventional guidelines to not eat too much fat and not to eat too much saturated fat. So if you have these people who end up restricting in all areas, then they might not eating enough protein, they might not be eating enough fat, they might not be eating enough calories, like, it literally could be a matter of undernutrition in order to comply with blood sugar targets. And this is something that we have to be careful with.

We also, I think, we need to give better nutrition advice. Because you can eat a very nutrient-dense diet, actually a more nutrient-dense diet when you're not so crazy high on the carbohydrates. But you have to be okay with eating more fat, right?

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: And that is scary for people who are following the conventional guidelines.

Andrew: Yeah, it's such an interesting mind flip. Take us through that, actually. You're known for developing real food, nutritional protocols for managing gestational diabetes. Given that there's such an issue, you know, we already have an embedded obesity issue in our societies. We have this thought in our head about a healthy, chubby baby. And there is some truth to that. But then we’re, you know, the reality is that they're just simply overweight.

How do you talk to patients about changing their diet away from what they think is good, because more weight is good, it means survival and happiness and things like that. To, you know, real food integration into their lifestyles?

Lily: You know, it's tricky because there are some, sort of, cultural bias towards bigger babies. I mean, certainly if you go back even 100 years, having a bigger baby meant, you know, higher fat stores and probably better survival.

But how were those babies, what made those babies grow bigger? Well, if you go back even 100 years, you weren't having this massive quantity of refined carbohydrates and sugars that we're having now.

Andrew: No, that’s right.

Lily: So I think big babies of the past were a lot healthier than a lot of the big babies of the present that we're seeing. You can still have like a plenty good size baby with a diet that's not excessive in carbohydrates and good blood sugar control. You know, I am somebody who didn't have gestational diabetes, didn't gain beyond the recommended guidelines, and my kid was still eight pounds, two ounces, you know? So it's not like you're guaranteed to have a small baby if you have good blood sugar control…

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: …or you don't eat a lot of carbohydrates, so I'll say that first of all.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: But a lot of my, you know, one-on-one work with people is about building the nutrient density of their diet. Like, let's make sure you're getting your micronutrients in first. Like, these are the nutrients that are most important, for example, for your baby's brain development. So we're looking at choline and vitamin B12, and DHA, and iodine, and zinc, and iron. And then you look at where do you find those nutrients in food?

And you don't get high concentrations of those nutrients in refined carbohydrates or even whole grains. You end up getting a lot of those nutrients in animal food. And so just by doing some basic education on like, "These foods are good for you because...It's okay for you to eat more of this because..." helps people make that shift without having to get obsessive about macronutrients or counting things.

Andrew: Okay, so there, of course, we first run into one of the major issues and that is hunger. How do you get over the hunger?

Lily: Yeah, well, you know, I'm not telling people to go hungry. I'm actually a huge proponent of mindful eating and honouring your hunger and fullness cues. So, the thing about making that shift to more nutrient-dense foods, which just so happen to be higher in protein and fat, is that they are more satiating and they naturally don't result in a big spike in your blood sugar and that's the big spike in your insulin production, and thus, with better-balanced blood sugar, you aren't as "hangry" as often. I'm about people eating enough food. Mine is certainly not calorie-restricted in any way. I think a lot of women following the conventional advice where you're supposed to eat a certain amount of carbohydrates, you're supposed to not eat high fat, you're supposed to limit your intake of meat, you're supposed to not salt your food, so it tastes awful, I mean, you just end up in this crazy blood sugar roller coaster and hunger all day long.

Andrew: Yep.

Lily: I mean, I just did like a 10-day experiment wearing a continuous glucose monitor and had, you know, my usual breakfast most days and watched the nice, even blood sugar line and had good energy levels. We're talking like eggs, and vegetables, and sausage or bacon, or something with it. But then the last day I was like, let's test this out. Let's see what happens if I follow the recommended pregnancy diet, which had oatmeal, milk, and strawberries, and my blood sugar went crazy.

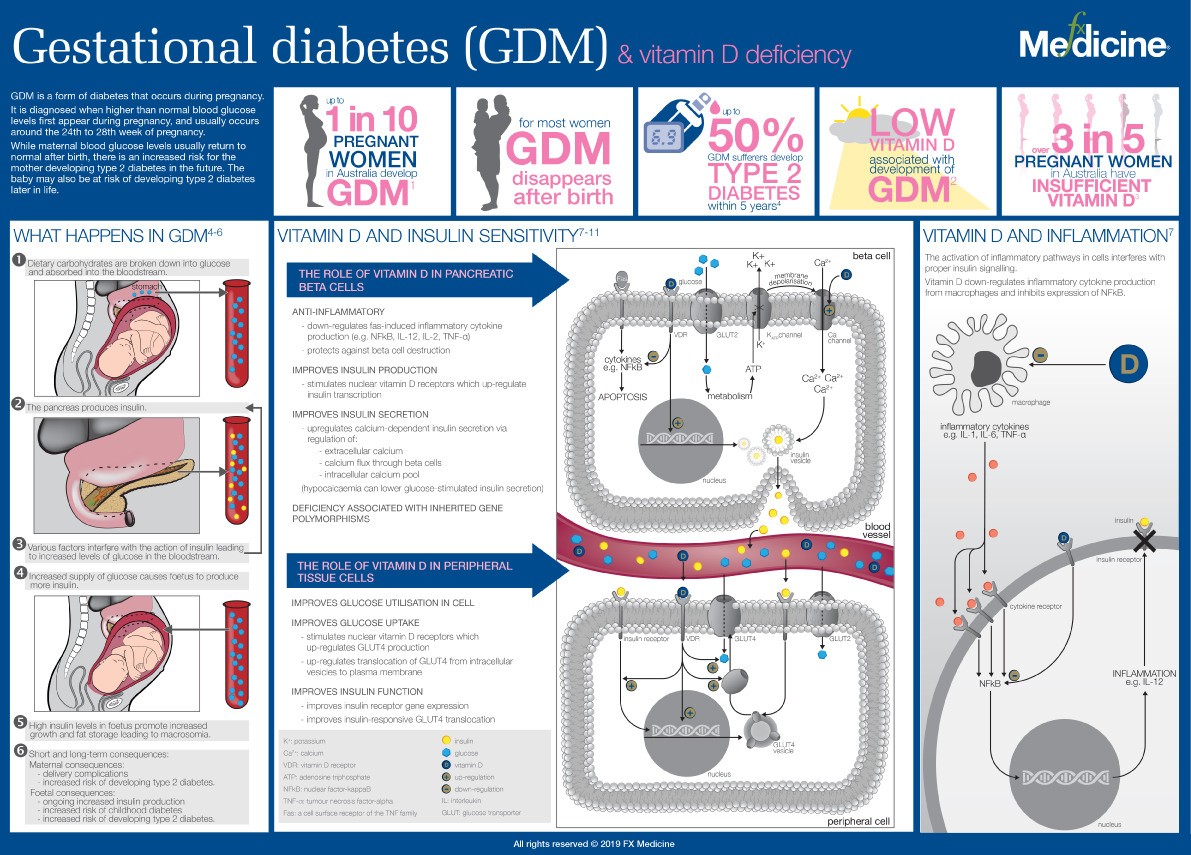

Gestational Diabetes (GDM) and Vitamin D Deficiency - INFOGRAPHIC

Andrew: Wow.

Lily: And I was starving within two hours…

Andrew: Right.

Lily: …which is something I've always observed in myself and is why I don't tend to eat super high-carb breakfast and tend to not eat oatmeal for breakfast anymore. But it was crazy to see it on a graph. It's like, we think it's this whole having the willpower to fight through, you know, just go hungry longer or something.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: It’s like your physiology is trying to work in your favour. Like, it sees an impending crash in your blood sugar happening really soon, it's going to tell you to eat something.

Andrew: That's right.

Lily: So a lot of the hunger things are self-resolved by just eating a different balance of foods, really.

Andrew: Yeah, you know what though? Your simple experiment has just laid waste to the, you know, standard American diet, standard Australian diet guidelines, with such a simple experiment.

Lily: It is crazy. And I actually have a write-up coming up on my blog soon on my whole experiment wearing the continuous glucose monitor, looking at, you know, what some of the data we have from CGM studies and people without diabetes. And there was one that came out recently where they did...I believe it was out of Stanford. I have to go back to the original studies, but they had CGMs on a group of non-diabetic, pre-diabetic, and type 2 diabetic people. And in part of their study, they gave a test meal and one of their test meals was cornflakes and milk.

Andrew: Right.

Lily: Do you know that 80% of these people had blood sugar excursions to the pre-diabetic range, which is over 140 milligrams per deciliter, which you'd have to convert that to your millimoles per liter, and 22% or 23% had blood sugar excursions above 200…

Andrew: Oh my god.

Lily: …which is in the type 2 diabetic range?

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: I mean, if 80% of people are having insane blood sugar spikes from cornflakes and milk, how can we pretend that this is good for people?

Andrew: Yeah, I just…

Lily: It’s not because there's a lot of data on glycaemic variability being a predictive marker of things like adverse cardiovascular events and the development of later type 2 diabetes. So, you know, it's one of those things where they say a diet can't be a cause, but the data seems to be pointing us in the direction that maybe it's not always the cause, it certainly could be. I think if I continued to assault my pancreas with oatmeal every single morning with blood sugar spikes in the pre-diabetic range, do you think my body would eventually get insulin resistant and eventually steer towards pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes? Yeah, it's just that that takes 10 to 20 years for a lot of people, you know?

Andrew: Yeah, no, I don't know, you must have been banging your head against the wall during the later stages of your studies.

Lily: The thing is I've realised you can't wait for the guidelines to change. I mean, I have worked in public policy, I've worked with the State of California's diabetes and pregnancy program, working on their guidelines. And of course, this was before I had all the clinical experience to see how poorly those guidelines perform. But just to give you a little example, even though I think we were doing good work, I mean, sometimes making the subtlest changes to the guidelines would take six months of arguing back and forth…

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: …on the research and ultimately, all of these things come down to a committee opinion. And I don't know how soon we're going to see it shift. I mean, I read a lot of research studies just for fun, even though that sounds really boring to most people, and the abundance of evidence we have supporting a lower carbohydrate diet, not necessarily needs to be super low carb or ketogenic or anything, but the evidence we have, even if we're looking just on like, refined carbohydrates and sugar being problematic for our blood sugar, and our insulin, and our lipids, and our markers of inflammation. And just overall lower nutrient density in your diet, when you eat a greater proportion of these foods and they displace more nutrient-dense foods, it just seems so obvious.

Andrew: What do you steer pregnant women towards when they're just starting their journey of change? You know, they're just starting to introduce more fat, less carbs, more nutrient-dense, calorie-light foods.

Lily: First of all, I think we have to make sure that the person knows how to identify, like, hunger cues from just an appetite or a craving.

Andrew: An emotional type thing, yeah.

Lily: Not that either one of those things is wrong. But like, if we're used to eating junk food, our taste buds and our brain chemistry wants that heavy hit of intense sweetness or fake flavour or whatever that's in the food. There's a whole book on it, "The Dorito Effect," I think it's called. So that might be a separate thing from true hunger, which you feel like below the neck, like a gnawing in your stomach or a drop in your energy levels or like a slight headache or something like that. So I like people to be clear on what it is and I think you can actually appease both worlds, meaning if you have like a craving for a specific thing, there's probably a way to meet that craving in some way in a less sugary way.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: It's usually sugar so I'll just go with that.

Andrew: So does that mean we can't have ice cream?

Lily: Yeah, so with ice cream, like a really good one, and I'm not against ice cream as a whole, in fact, for GD, ice cream might be one of the better, like, regular desserts you can have because it's so high in fat already, that even if you do, you know, a half cup portion might be like 15 grams of carbs, which is still like higher than something that's lower carb but it's not like 60 grams of carbs that you get in a slice of cake.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: And it has some fat that's at least satiating, right. But to take that a step further and to do it really like low sugar, low carb, you know, frozen berries and heavy whipping cream either mixed up or fully blended up to make almost like a fatty sorbet, that like really hits the spot.

Andrew: Okay.

Lily: But it's giving you very, very little sugar.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: It's also, you know, you're getting calories in there, you're actually meeting your hunger needs by providing fuel. I kind of dislike the approach of trying to fill up on volume like, "Oh, just drink more water or have this, like, broth or have this dry salad and, like, you'll feel better." Like, no you won't because you're not giving your body calories, your body is not dumb. I think we need to be smarter about, okay, you're hungry, you need some food of substance.

Andrew: Absolutely.

Lily: You need some nuts to fill the void, maybe some cheese, maybe a burger, or some avocado, or you can have those things with vegetables. You just can't expect to like, fill a hunger void with carrot sticks.

Andrew: No, that's right.

Lily: They don't work on their own.

Andrew: The old guidelines were, you know, the salad is healthy but what you put on it is not. It doesn't have to be that way…

Lily: Right.

Andrew: …when you're talking about extra virgin olive oil and, you know, some beautiful toppings that you can…

Lily: Right.

Andrew: …avocado you mentioned.

Lily: Right.

Andrew: As you say, there's extra facets of flavour, for me, like you can really enhance it.

Lily: Absolutely. And not only that, but you're actually improving your nutrient absorption of the nutrients that are in the vegetables that go with it.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: There’s legit, solid research on this where the phytochemicals, like the beta carotene and the astaxanthin and the lycopene and these antioxidant-like compounds that are in vegetables, the ones that are fat-soluble mean that they require fat to be absorbed. So you can absorb more of these beneficial anti-inflammatory compounds that are in your plant foods by eating them with a sufficient amount of fat. So it also makes them taste better so you're actually going to eat it. I mean, a dry salad has never been appealing, but you put on a really good balsamic and olive oil dressing, and avocado, and some goat cheese, and some pine nuts, or something, and now it actually tastes good…

Andrew: Yep. Yep.

Lily: …and you'll willingly eat it right? So it's a double whammy.

Andrew: Absolutely. So I know I've come back to this again, but with these people who are carb slaves, how do you get them to awaken to new types...I mean they're going to need new types of food.

Lily: Right.

Andrew: I guess for them, it's like, you know, eating fermented penguin. It can be that alien. So how do you get them to open up and to say, "Look there really is this stuff that actually tastes good, you have to change though?"

Lily: A lot of that can be conditioning, which could go back to a very young age if they didn't have vegetables well-prepared in their household, you know, like, over-boiled brussel sprouts taste awful.

Andrew: Awful.

Lily: But if you slice them in half and you roast them in, like, bacon fat with enough salt and some herbs. So I think a lot of it comes down to preparation. So I usually will talk to people, if they're really resistant to eating vegetables, I would ask, you know, if you can imagine one vegetable you might enjoy or might be willing to try, like, what would it be? And then they tell me and then we talk about preparation methods that would actually make it taste good.

Andrew: Got you.

Lily: And I just start with the easy route. You know, not everybody needs to like salads. I like salads, but only in the summer. I don't eat them in the winter. It's weird to eat cold, raw vegetables in winter. I want, like, cooked stuff.

Andrew: Yeah, yeah.

Lily: I don't need people to get on board with eating all the things all the time. Or even to like every single vegetable, it's just about finding some of them. And then oftentimes, it's giving them permission to add fat and salt to them, which have typically been taboo. And it's amazing what happens when you add salt and fat to vegetables, they taste good. So it's as easy as that. I mean, I even have an old freebie ebook on my website. I did recently update it, but it's "How to Make Vegetables Taste Good." And it's that, it's all tips and tricks and some recipes for getting people, you know, less scared about trying some vegetables that maybe they've never tried before or maybe they've tried them and they tasted awful. And it's like, wait, try it this way, you might like it.

Andrew: Yeah. Yeah.

Lily: So give it a try.

Andrew: You mentioned something just before about certain micronutrients. Are there any particular faves, heroes, standout micronutrients that impact glycemic control?

Lily: Well, that's a good question. So magnesium is a big one. Magnesium is known to affect insulin resistance, and it does tend to be lower in women with gestational diabetes. So that's one to definitely have on your radar. And in terms of food sources, we're looking at your dark, leafy greens, which are good for so many other micronutrients, you're looking at some nuts and seeds, especially like pumpkin seeds and sunflower seeds, seaweed, fresh herbs, chocolate. If you do a really dark like 90% chocolate, you're not going to get a blood sugar spike because there's not a lot of sugar in it, but you do get a decent amount of magnesium. Another micronutrient that's big on blood sugar is vitamin D…

Andrew: Yes.

Lily: …and that tends to be lower in women with gestational diabetes. And moreover, women with lower vitamin D levels tend to have higher blood sugar levels overall. So if you do get diagnosed, that's definitely another...I think every pregnant person needs to be checking their vitamin D levels personally…

Andrew: Absolutely.

Lily: …because it plays so many important roles in your health and fetal development and everything. But especially when there's also a blood sugar issue identified, you've got to be looking at vitamin D. There's so many more, I mean chromium, vitamin B1, vitamin B6, there's a lot of nutrients that are involved in glucose regulation.

Andrew: What about things like, in a roundabout way, I'm thinking iodine here. Like, it's a massive issue in Australia where we're getting marginal to moderate iodine deficiencies being seen in all populations. But you know, kids...forgive me if I'm wrong in stating this but I understand that it was a professor...Cresswell Eastman is the standout professor in Australia who's just on the bandwagon of iodine and he's tearing his hair out trying to get this iodine issue across to doctors because they're just not waking up. They're just not realising the prevalence of iodine deficiency. Where I'm going here is, you get iodine, which is intrinsic, obviously for many things, but also thyroid and then if you've got a low thyroid output…

Lily: Yep.

Andrew: …then you've got a predisposition for GDM.

Lily: It's all related, right, because your thyroid and all your blood sugar regulation is part of your endocrine system.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: So it's absolutely related. And I feel like iodine deficiency, I'm glad you brought it up because not many people talk about it. And there seems to be a big disagreement in the natural health field of some people who are anti-iodine and some people who are super pro-iodine, and it seems like it's hard for people to find their middle ground.

Andrew: I'm anti stupid doses of iodine.

Lily: Right, I think we can agree on that. But just getting sufficient amounts of iodine is tricky. Like, one study in the U.S. found that 57% of pregnant women are deficient in iodine.

Andrew: Wow.

Lily: We know that iodine, this is from the "Journal of the American Medical Association," is the leading cause of preventable intellectual disability worldwide.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: It is so crucial to brain development, so crucial to thyroid function, which in pregnancy plays a direct role in brain development. And yes, it does also influence your insulin resistance as well. It's definitely a part of the missing link. And in terms of dietary sources, seafood, whether we're talking like fish or shellfish and seaweed, all the things that come from the sea are the major source. And if people are being scared off from eating fish because of overblown concerns about mercury or food safety or whatever, then you're pretty likely not going to consume enough iodine.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: Then your next best food sources...and this is in the US, it does vary depending on the region you're in. The next best food sources will be eggs and dairy products.

Andew: Yes. Yes.

Lily: Well, say you don't like eggs or maybe you've been scared away from eating eggs due to food safety concerns over those, or maybe you're paleo or feel better, like, not eating dairy and that's cut out, then what's left? Like, you're prenatal...In the US only half of the prenatal vitamins have iodine in them. So that's not necessarily going to be a reliable source. Your next would be iodised salt, which has no redeeming qualities other than the iodine content, but even the iodine content is affected by exposure to heat, and air, and humidity, so it might all be evaporated from the salt by the time you eat it, you know. So it's like what do we do? To me, I think it points to the importance of regularly consuming, you know, safe types of seafood.

Andrew: Yeah.

Lily: But regularly including that as part of your diet because you're not only ticking the iodine box but you're also getting selenium, vital for thyroid health, you're getting DHA, you're getting iron, and zinc, and B12, and B6. So you're getting a lot of micronutrients in seafood that you could possibly not be getting enough of if they're not in your diet whatsoever. Or if you're like, "Oh, I don't eat fish so I just take fish oil." It's good for your DHA, does nothing for your iodine.

Andrew: Yeah. No, that's right.

Lily: So it's just tricky, like the more things that are cut out of the diet, the more...you have to kind of play recon and try to fill in the blanks and figure out what might be missing. And I think probably other than myself, there's not many people who would be thinking of all of these things.

Andrew: I don't know about the American guidelines but in Australia, I think it's interesting that iodine is the first micronutrient that's been advocated to be taken as a supplement for pregnant women, it's not folic acid. What they're saying is you need to eat your green, leafy vegetables and, by the way, all the bread's fortified, they're not saying to take a supplement necessarily.

Lily: Interesting. Here in the States, the main supplement that's pushed is folic acid, and I don't see iodine widely discussed. It's discussed in academia but doesn't, like, trickle down into, like, public policy messages like these widely discussed. And I really think it's a matter of, you know, if we require that prenatal vitamin manufacturers supplied the RDA for iodine, at least we'd make sure that part is covered.

Andrew: Yes.

Lily: I think they just assume that, well, salt is iodised, you're covered. Whereas it sounds like in Australia, it's like, the bread is fortified, so you're covered on folic acid. It sort of flip-flopped up here.

Andrew: Yeah, that's right. Yeah. Lily, thank you so much for taking us through this because it's a very, very important issue. We obviously know how prevalent it is, but it's a burgeoning, a worsening issue that we see in our society. And what you're doing is lessening it, so thanks so much for joining us on FX Medicine.

Lily: It was my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Andrew: This is FX Medicine, I'm Andrew Whitfield-Cook.

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.