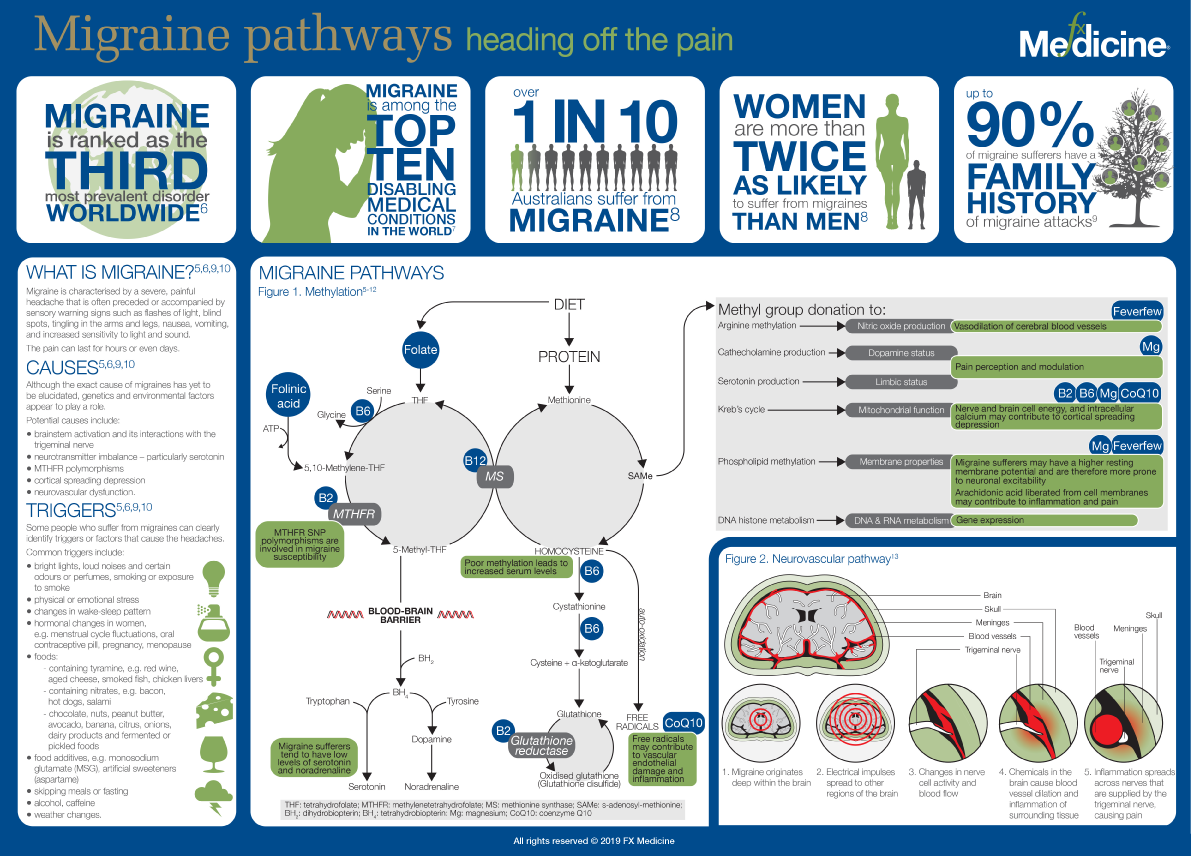

For about 2 million Australians, migraine is a significant and debilitating condition. Susceptibility to migraine is normally inherited, with certain parts of the brain adopting a seemingly hypersensitive response to certain stimuli. The pain nucleus of the trigeminal nerve becomes spontaneously active and pain is felt in the head or upper neck and blood flow in the face and scalp increases reflexly.[1]

The relationship between magnesium levels and migraine has been described through several mechanisms. Due to its effect on calcium channels, magnesium deficiency can have an influence on central neuronal hyperexcitability in the brain cortex, resulting in increased intracellular calcium, glutamate release, and increased extracellular potassium. Low levels of magnesium can also result in reduced nitric oxide synthesis and release with a corresponding decrease in blood flow to the brain. This is compounded by increased platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction further contributing to the underlying triggers for migraine.[2]

Magnesium deficiency also promotes neurogenic inflammation, mediated primarily by elevated levels of substance P. The enzyme most specific for degrading this neuropeptide is the magnesium-dependant neutral endopeptidase. Studies have demonstrated that inhibition of neutral endopeptidase results in elevated levels of substance P and greater oxidative stress,[3] two factors implicated in the aetiology of migraine.

Researchers have also proposed that the brain cells of some people with migraine may have a mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in impaired oxygen metabolism. Magnesium supplementation has the potential to increase the mitochondrial energy of migraine sufferers through its role in glycolysis, Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Likewise, riboflavin (vitamin B2) and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) play central roles in mitochondrial energy production in the brain with several studies showing therapeutic doses of these nutrients result in significant reductions in migraine frequency and duration.[4]

Migraine with aura is also linked to MTHFR C677T polymorphism, especially TT genotype. Recent studies showed encouraging results on improving migraine disability by supplementation with vitamins B6, B12 and folic acid. The clinical consequences of elevated homocysteine plasma levels include endothelial cell injury, spontaneous trigeminal nerve cell firing leading to inflammation in the meninges. Dilation of cerebral vessels is thought in part to cause the pain associated with migraine. Oxidative damage to the vascular endothelium via formation of superoxide from the production of oxidised homocysteine may also increase the likelihood of migraine.[5]

This infographic focuses on some of the important research in support of the therapeutic use of these nutrients for the safe treatment and prevention of this painful neurological disorder.

RESEARCH

- Lance J. Migraine and other headaches: a practical guide to understanding, preventing and treating headaches. East Roseville: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

- Samaie A, Asghari N, Ghorbani R, et al. Blood magnesium levels in migraineurs within and between the headache attacks: a case control study. Pan Afr Med J 2012;11:46. [Full text]

- Weglicki WB, Chmielinska JJ, Tejero-Taldo I, et al. Neutral endopeptidase inhibition enhances substance P mediated inflammation due to hypomagnesemia. Magnes Res 2009;22(3):167S-173S. [Full text]

- The migraine trust. Magnesium, riboflavin, co-enzyme Q10 and migraine. Migraine News 2007;93:10-11. Viewed 5 Jan 2015, http://www.migrainetrust.org/assets/x/50129

- Lea R, Colson N, Quinlan S, et al. The effects of vitamin supplementation and MTHFR (C677T) genotype on homocysteine- lowering and migraine disability. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2009;19(6):422-428. [Abstract]

- Headache classification committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia 2013;33(9):629-808. [Abstract]

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2163-2196. [Abstract]

- AIHW Australian GP Statistics and Classification Centre, 2006. SAND abstract No. 83 from the BEACH program: Prevalence and management of migraine. Sydney: AGPSCC University of Sydney. ISSN 1444-9072 [PDF]

- Migraine. Mayo Clinic 2013. Viewed 5 Jan 2015, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/migraine-headache/basics/d...

- Chawla J. Migraine headache. Medscape 2014. Viewed 5 Jan 2015, http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview#aw2aab6b2b2

- Stuart S, Cox HC, Lea RA, et al. The role of the MTHFR gene in migraine. Headache 2012;52(3):515-520. [Abstract]

- Nemecz G, Combest WL. Feverfew. Viewed 5 Jan 2015, http://web.campbell.edu/faculty/nemecz/George_home/references/Feverfew.html

- Press kits - the pathways of migraine illustration. National Headache Foundation 2007. Viewed 5 Jan 2015, http://www.headaches.org/press/NHF_Press_Kits/Press_Kits_-_The_Pathways_...

This image by FX Medicine is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

More information about how to share/use the infographics for personal use.

If you interested in using any FX Medicine content for commercial use please contact us.

DISCLAIMER:

The information provided on FX Medicine is for educational and informational purposes only. The information provided on this site is not, nor is it intended to be, a substitute for professional advice or care. Please seek the advice of a qualified health care professional in the event something you have read here raises questions or concerns regarding your health.